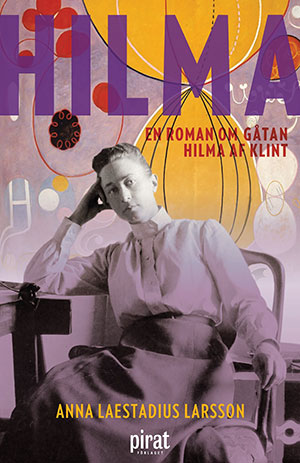

Hilma: En roman om gåtan Hilma af Klint by Anna Laestadius Larsson

Stockholm. Piratförlaget. 2017. 323 pages.

Stockholm. Piratförlaget. 2017. 323 pages.

Seeing to believing: it could be the motto for this book. Hilma, “A novel about the enigma that was Hilma af Klint,” is a captivating, intelligently fictionalized “life” of a painter who has only recently become internationally famous, but it seems hard to engage with the character Hilma af Klint. Her fervent—and, yes, enigmatic—psychic beliefs dominate her story, increasingly taking over from what we instinctively warm to as “normal” preoccupations. But, seeing her paintings, manifestations of another world perceived by her alone, is not only an overwhelming experience but also imparts meaning to her as a character and as a person.

Hilma af Klint was born in 1862 into a comfortable upper-middle-class family. She was well educated for a girl of that time and class; her father had enchanted her with mathematical games and stories of scientific advances ever since she was a clever, fey child. She read On the Origin of Species while still a schoolgirl, partly because she found Darwin’s theories a good way to stop the spirit of her dead older sister, Anna, from spooking her. For the rest of Hilma’s life, her art was inspired by the tensions between our biological existence and the spiritual messages flowing into her mind, mostly in a quasireligious flow of high-toned moral instruction.

A young woman at a time when the barriers against women doing anything other than getting and being married were breaking down, Hilma was eventually allowed to study art seriously. During a period as a struggling painter of landscapes and portraits, she became part of The Five, a group of women with similar interests and backgrounds. The group served as an emotional hothouse that encouraged Hilma’s few love affairs—all with other women—as well as her growing fascination with esoteric knowledge. The most extraordinary part of her life as an artist followed from a gradual, instinctive rejection of the demands of bodily pleasures, from food to love, until she had eschewed just about everything but contemplation of nature (late in life, she studied mosses and flowers with a botanist’s focus on detail) and painting. af Klint would have understood what her contemporary and potential soulmate Kandinsky meant by seeking “to symbolize the innerer Klang or inner need of the artist.” Spiritual guidance drove her to express transcendent truths in abstract shapes and glowing colors on very large canvases—the extraordinary Temple series alone contains almost two hundred of these. Text, including spirit “words,” as well as elements of mathematics and biology are included in the images.

Anna Laestadius Larsson deals ingeniously with the challenge of portraying the woman as well as her work by creating a frame story: eighty-two-year-old Hilma tells her grown-up nephew Erik about her life. We gain insights into her steadiness of purpose and personal magnetism; Erik is deeply impressed both by his aunt and her art, but—like so many of us—confused by the talk of spirits. Hilma’s storytelling explains a great deal about her, including her fundamental lack of interest in other people.

Long extracts from contemporary records, including Hilma’s own, are inserted to inform us about the rituals of The Five and, later, the role of the Theosophists. Laestadius Larsson comes across as an empathetic, gentle narrator, especially when Hilma and her female friends yet again come up against the restrictions of an unequivocally male-dominated society. The historical reality that surrounded these men and women is carefully and illuminatingly drawn.

af Klint, who ruthlessly burned all her private papers, tried to express her convictions in writing for posterity. She filled notebooks with drawings and commentaries and wrote a 2,000-page manuscript entitled “Studies of the Life of the Soul.” Until her paintings suddenly emerged into the international limelight, all these efforts to make herself understood were comprehensively ignored as were her paintings, although partly at her own insistence. As Laestadius Larsson shows, the reception for abstract art was angry and resentful during af Klint’s lifetime. Her work, she declared, was to be kept under wraps until at least twenty years after her death; it took about fifty years before she was recognized as the remarkable artist she is.

Anna Paterson

House of Glack, UK