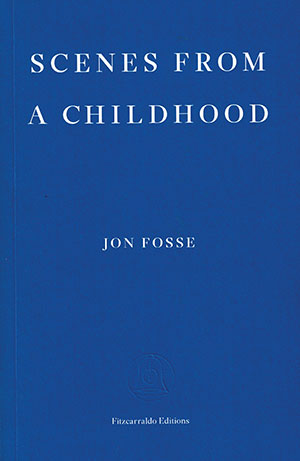

Scenes from a Childhood by Jon Fosse

London. Fitzcarraldo. 2018. 153 pages.

London. Fitzcarraldo. 2018. 153 pages.

Ever since Karl Ove Knausgaard published the first volume of My Struggle, international attention has equated much of the modern Norwegian novel with his name—that is, despite My Struggle itself doing its part to remind us that today’s Norway knows other writers besides its author. In the fifth volume of this autobiographical series, for example, we stumble across an account of a shy tutor at a Bergen writing academy named Jon Fosse.

Fosse, who today is largely known and hailed for his plays, has also produced several pieces of prose, which are only slowly gaining popularity in the English-reading world. Fitzcarraldo Editions—an independent UK publisher—is now endeavoring to accelerate this process, starting with Damion Searls’s translation of Scenes from a Childhood, published earlier this year.

Scenes from a Childhood is a collection of five pieces of short fiction written between 1987 and 2013. Its most striking feature is the range in quality between the individual stories, with earlier ones tending to outshine the later. The piece lending its name to the overall publication—written in 1994—is a compilation of chapters recounting individual situations of a childhood that seems to belong to the author. Ranging from three lines to two pages in length, these chapters loosely connect without ever forming a coherent plot. “And Then My Dog Will Come Back to Me” is the collection’s longest, second earliest, and clearly most impressive piece of prose. It recounts a man in rural Norway who murders (or not) his neighbor for having killed (or not) his dog. As his stream of consciousness progresses, we begin to notice inconsistences in the narrator's thoughts, and with the clarity of his mind slipping, the reality of recounted events becomes increasingly blurry. The buildup of tension and its slow dissolution in the fog of the narrator’s mind is carried out masterfully.

Regrettably, on the opposite end of the spectrum, one must list the 2013 story “Dreamt in Stone.” Thankfully much shorter than the collection’s better pieces of fiction, it might be best to let it speak for itself: “And then you say. And then there was someone who said something to me and I tried to get up but I couldn’t, and then there was someone who helped me get up. And then I stood there. And then I opened a door. And then I went in the door and shut it behind me. And then, you say. And I say that I don’t remember anything and then I remember that I woke up and I was lying inside on the floor. I got up. I was standing. I walked.” Simplicity of language carries much of Fosse’s stories in this collection, but he has tragically taken simplicity of style too far in some of his writing.

Despite their varying quality, we do find glimpses of skill and innovation in all of Scenes from a Childhood’s stories. Still, from this collection alone, it remains difficult to comprehend why people are pushing Fosse as a contender for the Nobel Prize.

Felix Haas

Zurich, Switzerland