The Aesthetics of the City: A Conversation with Youssouf Amine Elalamy

Born in Morocco in 1961, Youssouf Amine Elalamy is a writer and visual artist. He is the author of nine books, three of which deal with the phenomenon of migration. Initially written in French, his books have been translated into several languages. Elalamy is a professor at Ibn Tofaïl University in Kenitra, Morocco. He is the recipient of the “Grand Atlas” literature prize (2001) and the “Le Plaisir de lire” prize (2010) for his novel Les Clandestins (2001; Eng. Sea Drinkers, 2008). Elalamy also received the first British Council Literature Prize (1999) in the category of travel writing. Elalamy is a founding member and current president of the Moroccan Centre of PEN International. His latest book, Même pas mort, is an autobiograpy in memory of his father.

Nisrine Slitine El Mghari: Could you tell us a little bit about A Moroccan in New York?

Youssouf Amine Elalamy: For three years, I lived in New York City while pursuing my PhD in communication, which I obtained in 1991. Since I was working on the aesthetics of commercial culture, I was convinced that the right place for this field was New York City, one of the world’s, if not the world’s, capital of advertising. Take Madison Avenue, for example. Back then, I had never published any fiction or any creative writing. It was only about one year after I returned home from New York that the whole experience of New York City came back to me all at once. In a sense, the material was ripe by then. The book was a success, and I was pleasantly surprised, of course.

Slitine: How do you see yourself as a contemporary Moroccan writer?

Elalamy: I would say that I am in the field of creation. Today I might write a book. Tomorrow I might work on an art installation like the one I did in Amsterdam in my project entitled “A Novel in the City,” which went on tour in Marrakech, Rotterdam, Cologne, and Copenhagen. After that, I might do an art exhibition of installations or music or drama performances. And for me, all these artistic projects constitute writing. That is, regardless of the material I use, the piece of art I create represents writing. The only difference in this instance is that I do not write using letters; instead, I use forms, colors, substance, etc. Moreover, when I write, it is a way of composing, painting, and so on. In my opinion, it is exactly the same thing, except that this time I do it with the help of letters, words, and sounds.

For me, all these artistic projects constitute writing. That is, regardless of the material I use, the piece of art I create represents writing.

Slitine: In some works, you combine written and graphic texts as in your novels Miniatures and Tqarqīb ennāb (Chatter), both of which inspired art exhibits.

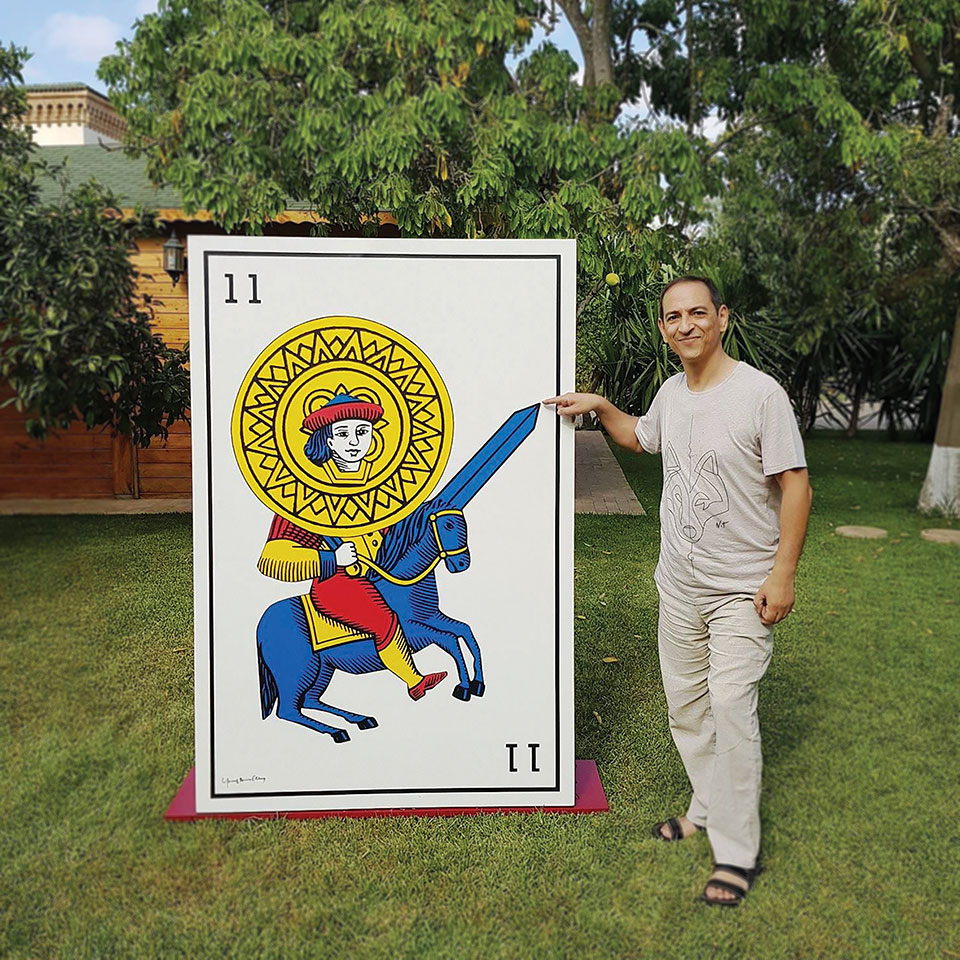

Elalamy: Absolutely. In Tqarqīb ennāb, I used handmade collages I crafted out of a popular Moroccan card game. I used the same concept to create large-format canvases that can reach up to three meters in height. The book Miniatures came with artwork as part of the “Miniatures” exhibit that toured around Morocco. Ultimately, I consider my work to be conceptual. To me, the importance lies in ideas I intend to convey to my audience.

Slitine: In 2008 you launched a collaborative project called “A Novel in the City” bearing the subtitle “Removing a Book from Its Cover.” Could you describe this experience both artistically and logistically?

Elalamy: My “Nomad” artistic project is an urban literary and “nomad” installation dispersed in the urban space of a city. Based on my novel Amour nomade (2013; Eng. Nomad Love, 2014), “A Novel in the City” is an original interdisciplinary and cross-border project. For the first time ever, a novel is published in space rather than in a book format. Space becomes a narrative in itself, a place of encounters, emotions, discovery, and exploration. Just as the space of the city helps read the story, the story, in its turn, takes readers on a walk through the city and helps them read it as well.

Writing in dārija was almost like a militant act on my part and also something personal.

Slitine: Tqarqīb ennāb is the first Moroccan novel written entirely in the Moroccan dialect of Arabic. Why did you choose dārija as a novelistic language?

Elalamy: Writing in dārija was almost like a militant act on my part and also something personal. It is my native language and the only language I spoke until the age of six. I then learned French and, later, English. While writing, I used a traditional notebook and pencil because I wanted to be able to erase, as I was used to the computer’s delete function. But to my surprise, when I started writing, the ideas came naturally.

Slitine: The aesthetic elements of this work are rather sophisticated. The text is succinct and very poetic. Why did you opt for rhymed prose?

Elalamy: I used rhymes in this text to show that daily language could be artistic. Unlike dārija used in malhūn or zajal, which are already poetic and could be hard to understand for most common Moroccans because of their refined terminologies, the kind of dārija in which I wrote this novel is that of the everyday. My idea was to elevate this ordinary language to literature, and that was the most challenging process in this experience for me. Moreover, the text offers different levels of reading. The first layer of meaning may seem anecdotal or humoristic, just like the images of the card game may at first look very familiar. But when the reader takes a closer look at the text, he/she discovers deeper meanings and hidden symbols.

This novel was performed as street theater in about ten cities including Rabat, Salé, and Casablanca by Théâtre Nomade, directed by Mohammed El Hassouni. It was staged in city squares to the public free of charge just like the traditional Moroccan ḥalqa (circle) of storytellers. Tqarqīb ennāb was also performed in an international street theater festival in France.

Slitine: In Sea Drinkers, you portray the dark social reality of contemporary Morocco and the disenchantment of the young generation through images of rural exodus toward the city, the expansion of shantytowns, unemployment, poverty, and social divisions, all of which lead young Moroccans to perilous illegal immigration to Europe. You go into great detail describing decomposed bodies of harrāga, or clandestine immigrants, washed up on shore, and you use photographic terms, specific dates, times, and geographic locations that give the narrative features of a documentary. As I was reading the book, I felt like I was watching a film. What do you wish to communicate through your narrative?

Elalamy: It is quite true that the way in which I generally write and construct my books is very much like directing a movie. In Sea Drinkers, I did not write the chapters in the same order they are presented in the book. I actually wrote different scenes separately. I approached this work like filmmaking, and sometimes I had to cut certain parts for cohesion just like a chef monteur (chief editor) would do in the movie industry. So, I am actually writing scenes—that is why I am not very surprised about the impression you had regarding the documentary trait of this book. In fact, there are many cinematic effects. You made a reference to the scene of the Spanish photographer using different filters and devices and describing the corpses, and it is quite true that I wanted this work to be visual, as a matter of fact.

Slitine: In this book, you have also expressed your idea of cinematic style through language. You have named one of your characters Houlioud in reference to Hollywood. Likewise, at the end of the narrative, in cinematic terms, one of the characters describes illegal immigrants’ dark reality, emphasizing that “if there’s no music, and no drumroll to accompany all this, no screens and no ticket either, it’s in order to say that for all those drowned souls on the sand, say what you will, this isn’t Hollywood.”

The piece of work is also reflecting on what it is doing, and this is very modern in the sense that writers do acknowledge that a work, any work, is an artifact, a construct.

Elalamy: Absolutely! That is a statement about representation as a whole. Whatever I say or write remains a secondhand experience. It is not the real experience of those people who drowned in the sea; rather, it is me representing those individuals. My writing is metafictional in the sense that I have a narrative, a fiction that reflects on itself as it unfolds. The piece of work is also reflecting on what it is doing, and this is very modern in the sense that writers do acknowledge that a work, any work, is an artifact, a construct. I definitely subscribe to the contemporary stance of writing, which is, as I am writing, I tell my reader, “Look, I am writing, I am constructing.” And I even allow some room to my readers to participate in the elaboration of the story, the concept, and even the writing. If we take the example of Sea Drinkers, you can see that there are some gaps within the text which, of course, call the reader to fill in.

Slitine: So, by inviting the reader to play such an active role in reading your novel, you define your writing style as untraditional and nonlinear; therefore, it is a writerly text calling for interaction and interpretation rather than a readerly text that conceals these literary elements, as Roland Barthes argues in The Pleasure of the Text.

Elalamy: Indeed. There is no fixity of meaning or elements. Things are floating on the surface like those dead bodies of harrāga on top of the water. The meaning appears and disappears just like Spain appears when the sky is clear and disappears when it’s cloudy. There is this idea that we’re between reality and illusion. Also, the text comprises a combination of poetic passages like the one in the chapter called “Chama,” where this character is about to die in the sea at night and sends a posthumous letter to her lover. Other passages, on the other hand, are dry and almost clinical, like a dissection of human bodies, a text written with a blade rather than a pen.

In regard to my writing approach, I would like to add that Barthes also quotes Larvatus Prodeo in a Latin expression that means “I advance pointing to my mask.” So I am not wearing a mask and trying to make you believe this is my identity, I am on the stage and pointing to my mask and telling you, “Look, now I am a writer.” But I am not always a writer (chuckles).

So I am not wearing a mask and trying to make you believe this is my identity, I am on the stage and pointing to my mask and telling you, “Look, now I am a writer.”

Slitine: Oussama, mon amour is another novel in which you address topical issues, namely pseudoreligious terrorism. Your novel was inspired by the May 2003 terrorist attack that targeted La Casa de España in Casablanca. Would you say that the twenty-first-century Casablanca in this novel represents a global city?

Elalamy: Let’s keep in mind that I did not name any street, district, or city anywhere in the book. Likewise, I did not mention any year. But maybe because I stated the fact that the protagonist (the suicide bomber) was traveling through the city to the hotel might have suggested that the action is happening in Casablanca.

Regarding whether Casablanca of the twenty-first century constitutes a global city, I would say yes, definitely. Because when I was writing, I had in mind any big city. If we are talking about Morocco, it could be Casablanca, but it could also be Rabat or Tangiers, or any other city in the Arab world. This is certainly the reason why I did not want to name the city or the streets, because if I did, I would limit terrorism to a specific place. Whereas, as you mentioned, this is a global concern, and it could happen anywhere in today’s world. I had to somehow create the illusion, at least in the reader’s mind, that the protagonist is moving within a specific city. Yet it is no-city, and if it’s no-city, it’s every or any big city.

Slitine: Could you comment on the aesthetic of fragmentation in your Drôle de printemps?

Elalamy: In this novel, I did not always want a link to exist between the 330 micronarratives to avoid an extremely boring reading experience. I wanted to keep surprising the reader through the change of links to keep him/her engaged. My goal was to find for that book a form that could reproduce the dynamics of the Arab Spring, which was a set of actions and reactions, a chain reaction like the card game. After the first action—a blow or touch—each piece of the forty cards comes down on top of the other. Likewise, my idea is that the breath of the reader, who will lean on the first section of the first page, will deal a blow to the first micronarrative, which will fall onto the second and so on. As you read, you understand the very dynamics of the text and also the logic of social discontent during the Arab Spring. The ill-treatment of Mohamed Bouazizi by the local authorities led him in his despair to kill himself, which caused another reaction in the street of the little town provoking another reaction in the capital of Tunisia, which then triggered a reaction in Egypt, etc. This particular construction allows me to encode the dynamics of the events’ succession.

Additionally, this unusual aesthetic was a tribute to the young people from the Arab world who shared images and videos on social networks mobilizing large crowds to go into the street and demonstrate. The small passages throughout the book resemble posts on Facebook or other social media. Similarly, because they work together, these posts and voices constitute a kind of network.

Slitine: This multiplicity of voices exists also in Tqarqīb ennāb. What does the ensemble of characters represent, and what inspired the idea of collages?

Elalamy: In Tqarqīb ennāb, I used thirty out of the fifty characters I created in Miniatures. The idea came to me one night as I was contemplating a building facing my window. In that construction, I saw people living under the same roof and sharing the same space, yet each of them was in a different bubble. This image was very representative of contemporary Moroccan social life. We all live under the same sky, nation, flag, political and government system, and yet we each live in our own world with our own concerns and desires, urges, and frustrations. I found it interesting that those individuals are together and yet not together; they don’t communicate with one another, and this is what actually inspired the structure of these two novels. In the book, the characters are all under the same cover—or building—the same structure, the same form, yet each one is isolated from the other. Also, the lack of communication is an important idea. Even in Drôle de printemps, all 330 voices are expressing something, and yet they do not communicate with one another, which is representative of today’s Moroccan society becoming more and more individualistic and divided.

In regard to the idea of graphic cards accompanying the written text, I was thinking in terms of iconography. I wanted some icons that would go beyond social classes, age groups, and even gender and could not find better images than the card games that all Moroccans have played, the same cards that fortune-tellers in our society use for readings. When you look at the small passages of Tqarqīb ennāb, it is similar in a way to snapshots where many elements come together as a part of the construction of the image.

November 2017