Editor’s Note

The page is both full of death and free of it. – Edwidge Danticat

The page is both full of death and free of it. – Edwidge Danticat

“And because my mother did not write letters and because I did not ever want to forget the things I wished my mother were telling me, . . . I tried to write them down in a small notebook I made from folded sheets of paper bound together by thread. In that notebook, I also sketched a series of stick figures, which were so closely drawn that they almost bumped each other off the page.” The young Edwidge Danticat, growing up in Port-au-Prince, corresponded with her parents in Brooklyn by means of letters, phone calls, and cassette tapes. Her father had immigrated to the US when Danticat was two, her mother when she was four; both were working in sweatshops at the time. The incipient writer/artist, binding sheets of paper together with thread, realized even then “how words—both written and spoken” could “transcend geography and time.”

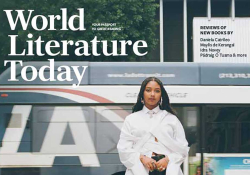

Danticat weaves that thread throughout her 2018 Neustadt Prize lecture, “All Geography Is Within Me,” which is featured here as the marquee piece in the cover section devoted to her life and work. As the daughter of a tailor and a seamstress, it seems only natural that the young Danticat would see in her parents’ needles a metaphor for writing as well as the etymological affinity between texts and textiles.

As World Literature Today’s most recent Neustadt Prize laureate, Danticat enlarges Haitian literature’s claim to serve as a “model” for world literature, as Michael W. Merriam argued in the March 2015 issue of WLT. “André Breton went to Port-au-Prince,” Merriam writes, “to tell Haitians that writing can be revolutionary, but Haiti had already proven that a revolution is, itself, an act of writing.” Danticat’s work embodies that revolutionary spirit, even in the diaspora, noting in her keynote that Haiti became the first black republic in the Western Hemisphere after the revolution of 1791–1804.

In Create Dangerously, her 2010 collection of essays subtitled “The Immigrant Artist at Work,” she writes: “. . . though we [immigrant artists] may not be creating as dangerously as our forebears—though we are not risking torture, beatings, execution, though exile does not threaten us into perpetual silence—still, while we are at work bodies are littering the streets somewhere.” When Danticat joined the 2017 protests against Donald Trump’s refugee ban at Miami International Airport, she enacted her own willingness to represent the limits of what humans are able to endure in her pages. In her conversation with Erik Gleibermann that begins on page 68, Danticat gives us a glimpse into how far she might go to inhabit those limits: “In The Dew Breaker, in order to write about that man, someone who could easily have been a devil with a horn on his head, I had to become someone like that. I had to step into the shoes of someone who can murder people.” Plumbing such depths permeates her work.

Toward the end of her talk at the 2018 festival, Danticat reflected on the beginning of her early story “Children of the Sea” (1991), the first story in her 1995 collection Krik? Krak! “I began it this way,” she writes, “because that story had reminded me that some people’s potential new beginnings can also lead to their end. Writing that story had reinforced for me the idea that the page—my writing home—has to also be free from death because creating anything, be it words, images, song, and dance, means that we believe in immortality, that we believe we can survive, even on the other side of the waters, even lòt bò dlo.” The themes Danticat sounds throughout her talk—the emphasis on beginnings and endings, death and immortality, the hunger for story, “internal” geographies (of words and memories), individual and community, bearing witness, immigration and imagination, and writing as an act of love—are woven throughout her essays, stories, and novels. Like Ariadne unspooling her thread, Danticat dares us to enter the labyrinth behind her.

Daniel Simon