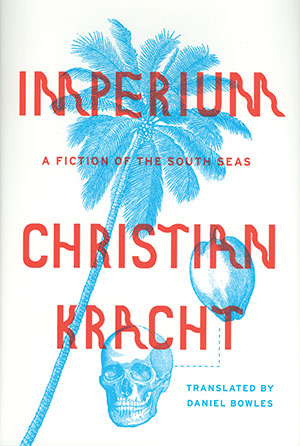

Imperium: A Fiction of the South Seas by Christian Kracht

Daniel Bowles, tr. New York. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 2015. ISBN 9780374175245

Daniel Bowles, tr. New York. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 2015. ISBN 9780374175245

The “imperium” of the title refers, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, to Germany at the “global zenith of [its] influence” around the beginning of the last century when it actually boasted colonies, including this one in the South Seas. It also suggests the heavenly utopia Kracht’s hero aspires to create here. The story is that of an overzealous pursuit of an idealism so ludicrous that it could come only from actual history—typical of that era of fads and fanaticisms. It is an idealism whose extremism Kracht admits has undeniable parallels to that of another “romantic vegetarian” whose dystopia became tragic historical reality all too soon after this one. This is the story of August Engelhardt, a nudist and vegetarian who is filled with the notion that the coconut is the “crown of creation”—it grows so high that it is closest to God and, apart from providing a complete food source, it can be used to make practically everything (furniture, houses, mats, dishes, ad infinitum). Exclusive devotion to it is tantamount to divinity.

Engelhardt buys an island plantation and has the natives gather the nuts and gets the products processed to be sold abroad. The letters he writes to promote his coconut products wind up, as Kracht recounts in fond detail, years later as toilet paper in other imperial outposts. At the same time he writes to attract fellow “cocovorists,” but this results only in some very minor and, indeed, ultimately abortive experiments.

The real Engelhardt died not long after the First World War, but Kracht’s fictive avatar persists until he is discovered by the US Navy as the Second World War is ending. Crew members clean him up and take him to Guadalcanal where they give him “a dark brown, sugary, rather tasty liquid to drink from a glass bottle slightly tapered in the middle” and “a type of sausage brushed with garishly bright-colored sauce that lies in a bed of oblong bread as soft as a down pillow.” I will leave it to the reader to puzzle out what these consumables might be, but I cite them as typically reflective of Kracht’s amusingly oblique, wonderful historical style (befitting the exotic tales of that era) and his even more wonderful humor.

The fates of both the zealots and of the natives are mostly sad, occasionally tragic, but when Kracht renders them in language ranging from theological casuistry to absolute slapstick comedy one hoots one’s way through the book. Serious lessons, yes, but hilariously told. Translator Daniel Bowles has done an excellent job in conveying these qualities in his highly faithful and exacting translation: a thoroughly charming read.

Ulf Zimmermann

Kennesaw State University