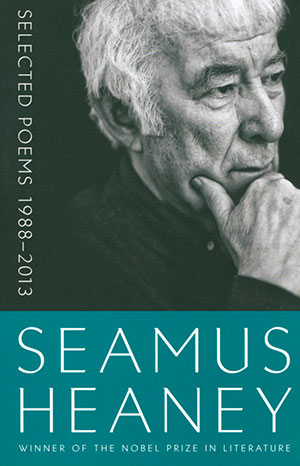

Selected Poems, 1988–2013 by Seamus Heaney

New York. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 2014. ISBN 9780374535612

New York. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 2014. ISBN 9780374535612

Farrar, Straus and Giroux has published Seamus Heaney’s Selected Poems in two volumes, the first including poems from 1966 to 1987, the second, 1988–2013. The strength of the poems in this second volume generally matches that of the first, with certain poems such as “The Rain Stick” and “Postscript” equaling anything in his entire body of work. Although one wishes for the greater fullness of a “complete poems,” thinking with fondness of some poems not included here, this collection nevertheless satisfies and serves to concentrate the muscular poetic force of Heaney.

Heaney himself preferred a poetry that was “unfussy and believable” and “the virtue of an art that knows its own mind.” His poetry is restrained and essential yet not terse, cramped, or epigrammatic. His poetics is willing to include “buttermilk and urine” in the same line but eschews flourish and ostentation. Though rhythmically formal, often written in masterful iambic pentameter lines, his verse has the feel of careful, natural speech (as Eliot said it should). We find a proportional balance to his use of imagery and rhythm as he focuses on the “real” world and ordinary lived experience. His sonic textures and precise diction are determined to accommodate the actual—no, to incarnate the actual in the language of his poetry.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that Heaney refuses to hint, gesture, comment, infer, or apply; he does these things as well. It does mean, however, that he is first interested in attending to the observable world. Here we find him in the aesthetic precincts of Wordsworth, Frost, and Bishop but with important differences. His work is not infused with a reverent pantheism nor does it overtly seek objective correlatives for a literal-as-metaphorical bilingualism; it does, however, share a willingness to allow life to lead to perceptions and knowledge that would otherwise be missed by the arrogating methods of the current avant-garde who appropriate the actual and force upon it a plasticity to be molded by the self-centered imagination. This, too, is something human, something poetic, but for Heaney it’s a matter of sequential priority that we first patiently attend or, as James Wright says in one of his poems, “look quietly.”

After all, there is a way in which life lives us, if we let it. If we are preemptively deciding the message, steering our thought, then we stand to miss the crucially important truths, experiences, messages we might find life altering. In “Postscript,” with its first line—“And some time make the time to drive out west”—brilliantly recalling that of Frost’s “Directive”—“Back out of all this now too much for us” (i.e., iambic pentameter comprised entirely of monosyllabic words)—we are led to understand the importance of venturing from our known territory, our pre-positions, and allowing a vulnerability to the unforeseen: “You are neither here nor there, / A hurry through which known and strange things pass / as big soft buffetings come at the car sideways / And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.”

Fred Dings

University of South Carolina