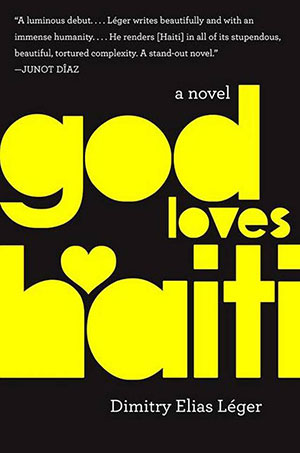

God Loves Haiti by Dimitry Elias Léger

New York. HarperCollins / Amistad. 2015. ISBN 9780062348135

New York. HarperCollins / Amistad. 2015. ISBN 9780062348135

In his debut novel, God Loves Haiti, Dimitry Elias Léger uses the 2010 earthquake in Haiti as the backdrop for a love triangle. A flaccid, fictionalized president—“the President”—and his much-younger, philandering wife—Natasha—are about to board a plane supplied by the United States government that will fly the newly wed couple to Florence to live lives of lavish, chosen exile. The latter’s lover, Alain, is locked in her closet in the National Palace and realizes he has been dumped.

After the thirty-five-second goudou-goudou, the three are separated and spend the rest of the novel on their own journeys of self-discovery. The president, once an impotent leader of the country, finds a capacity to lead in one of Haiti’s darkest hours. Natasha works to understand the connection between her highly collectible art and her legacy of being orphaned by parents who could not afford to care for her. Alain becomes part of a poor community working to emerge from the earthquake—even though he always lived in the rich Place Boyer unscathed by the disaster and where his parents wait and assume their only son is dead.

As the three trudge through the aftermath of the quake looking for each other, each finds a different relationship with God while attempting to understand Haiti’s propensity for disaster and its tenacity in recovering. Alain’s initial understanding that an earthquake just threw him from his car encapsulates Haiti’s relationship with catastrophe: “But there’s no history of earthquakes in Haiti. None whatsoever. His parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents never mentioned it. And picking apart the nation’s colorful, sorrowful, and thrilling history is all Haitians do. It’s a sport, the fucking national pastime.” Through their travels, the reader learns the backstory of the protagonists and how they have come to be in their position at the moment of the quake. The deft maneuvering among the three allows the reader to connect with each, and when they finally do find themselves in the same space—a church—the reader is satisfied with the novel’s climax.

The title derives from of one of the many conversations throughout the novel in which a character questions God’s “choice” to batter Haiti with tragedy and disaster. A priest explains to Natasha, “The earthquake was the latest sign that God loves Haiti.” She is incredulous, but he explains: “The way we Haitians suffer misfortune, deprivation, and disproportionate foreign enmity is right in line with the fate of chosen peoples throughout history. Biblically speaking, anyway. God may love us too much, I’d say.” Such conversations lead the three to come to terms with the trauma they face and the despair that surrounds them in a novel that offers the reader a true-seeming fictionalization of the disaster that decimated Haiti’s capital.

Colleen Lutz Clemens

Kutztown University