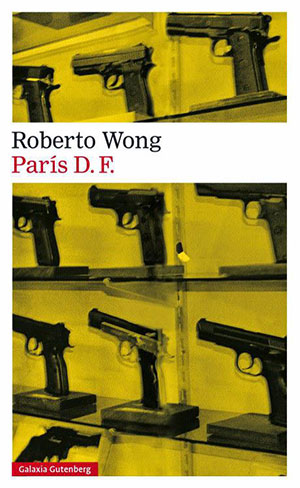

París D.F by Roberto Wong

Barcelona. Galaxia Gutenberg. 2015. ISBN 9788416252206

Barcelona. Galaxia Gutenberg. 2015. ISBN 9788416252206

París D.F., Roberto Wong’s first novel, won the Premio Dos Passos first novel prize in October 2014. The thirty-two-year-old Mexican-born writer’s short work is rife with sharp dialogue that captures the postapocalyptic hustle of Mexico’s capital city, whose immense population is besieged daily by corruption, violence, and pollution.

The protagonist of Wong’s novel, Arturo, is an aspiring poet who attempts to come to grips with an unfulfilling job and an insipid love life. He continues to be haunted by the death of his father, even while his mother is slowly succumbing to diabetes. One day, Arturo’s life is transformed when his workplace, a pharmacy, is held up by an assailant named Luis. After police haphazardly gun down the would-be robber—who bears a striking resemblance to Wong’s protagonist—Arturo, now traumatized by his close encounter with death, begins an existential journey across time and space, hoping to mend his disquieted consciousness.

Now uncertain of his existential proximity to the deceased thief, Arturo reevaluates the grim conditions and chance encounters that characterize Mexico City. Lamenting not having seen the city that inspired so many poets (Paris), he places a map of the European metropolis atop a map of Mexico’s capital. Spatial and temporal confusion ensues as Arturo explores his own psyche; the protagonist mixes up other characters and becomes involved—like Luis—in Mexico City’s violent and sordid demimonde.

During Arturo’s psychological journey of self-discovery—recounted in chapters that oftentimes alternate settings (Mexico City and Paris) but ultimately end up admixing locales—Wong mines liberally from surrealism. Thus Arturo takes to the streets of both cities like a Benjaminian flâneur, where he steels himself for the tritest bits of mass culture (sensationalist tabloids, lucha libre matches), even while sleeping with a prostitute and waxing poetic about a woman he’s never met—the suggestively named Nadia.

Wong does not conceal his indebtedness to surrealism. The author explicitly engages André Breton’s Nadja (1928) as well as Julio Cortázar’s short story from 1966, “El otro cielo” (“The Other Heaven”), which also examines a protagonist’s dialectic consciousness stretched tautly across two shores.

Like the surrealists, Wong’s interest in the spectacle, savagery, and even eroticism of public violence can ultimately be traced back to Comte de Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror. In the novel’s final scene, we see the would-be assailant, Luis, cajole Arturo to burn down his (Arturo’s) childhood apartment.

The conclusion offers a purifying vision of destruction: only by channeling memories properly, decathecting from past pain, and accepting the crippling contingency of the everyday can individuals transcend the ordinary. Indeed, the conclusion intimates Breton’s caustic, pithy pronouncement from his Second Manifesto of Surrealism: “The simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down into the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.”

Wong’s bright prose attempts to break with the political corruption and intense violence that hang over Mexico like smog. Like the surrealists, Wong, too, suggests that literature can be transgressive.

Kevin M. Anzzolin

Wheaton College