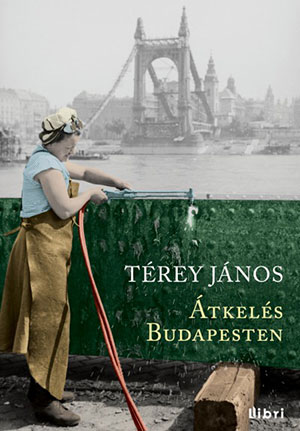

Átkelés Budapesten by János Térey

Budapest. Libri. 2014. ISBN 9789633103814

Budapest. Libri. 2014. ISBN 9789633103814

János Térey, one of the most significant Hungarian poets of the middle generation, has written a number of books in which he reinvents epic poetry, using this outmoded form to tell contemporary tales with a contemporary sensibility. His most recent work, Átkelés Budapesten (Crossing Budapest), is a volume of fourteen narrative poems, or “short stories,” as the subtitle says. Each story takes place in well-defined districts and streets of Budapest, some well known, others more obscure places that do not figure in guidebooks but are no less intriguing for that. The whole adds up to a peculiar perspective of Budapest, or rather “the serene ghost city that exists below or beside us.”

The stories are related to the locations in various ways and to various degrees. Sometimes the location is a mere backdrop; at other times, the sense of place imbues everything to the point of suffocation, as in the ballad-like “Those who are alive make noise,” a story that takes place on Svábhegy, a scenic spot in the Buda hills, where several buildings served as Adolf Eichmann’s headquarters after the German occupation of Budapest in 1944. In Térey’s story, a married couple buys an apartment in one of these buildings. The wife hears eerie sounds and sees will-o’-the-wisps at night in what is taken as a neurasthenic spell by the husband, until an old architect friend visits them and gradually recognizes the building as the one where he had been tortured by Eichmann’s henchmen.

Other locations include the mysterious Háros Island, a military zone that is off-limits for ordinary humans. In a story entitled “Disembarkation,” a music teacher, tired of his life and fed up with people, arrives on this untrodden island with a sprawling alluvial forest, but his escapade is frustrated by a sudden attack of the sciatic nerve. Loneliness, displacement, and peregrination to various places to find meaning are looming themes of this story and many others. In the lyrical “Early Winter,” a divorced husband now living abroad stalks up to the building where he believes his ex-wife still lives and watches her shadow as she passionately makes love to a stranger—an illusory image that turns out to be the shadow of a tree, shaking and trembling in the wind.

Desolate places, disconsolate characters, and their clichéd speech are redeemed by the elegant diction and the dispassionate tone, Térey’s trademark style: a strange mixture of cold matter-of-factness and compassion that reminds one of Edward Hopper’s paintings. Térey’s characters are very much like the flesh-and-blood people who walk the streets of Budapest today, but the narrative poetic frame at times alienates them to the point of becoming marionettes, impressions and reverberations of the place and time that weigh mercilessly upon them—their words, acts, and emotions are like spasmodic repetitions or miscarriages of earlier deeds of others, committed or left undone.

The word átkelés in the title alludes to a straight, direct crossing, whereas in fact the locations of the chapters are chosen randomly all over the city. The reading experience, on the other hand, decidedly has the feel of crossing a river—in the steady, eloquent flow of the narrative poem, people’s gestures, the names of time-bound objects, or turns of phrase determined by the age or class of the speaker sometimes give the impression of objets trouvés, flotsam and jetsam, emerging and inviting us to stop and take a good look at the reality that surrounds us.

Ágnes Orzóy

Budapest