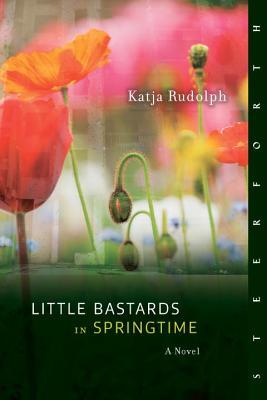

Little Bastards in Springtime by Katja Rudolph

Hanover, New Hampshire. Steerforth Press. 2015. ISBN 9781586422332.

Hanover, New Hampshire. Steerforth Press. 2015. ISBN 9781586422332.

Katja Rudolph’s Evergreen Award–nominated first novel follows the Serb-Croat Andric family—journalist father, pianist mother, teenage son, six-year-old twin daughters, and younger son, Jevrem, eleven—as the siege of Sarajevo destroys their happy lives, forcing them to flee to Toronto. Exploring how violence and diaspora shape youths who fight the status quo with their own misguided violence, Bastards promises a new thread in Balkan literature. But despite many lyrical passages, a solid plot framework, and historical accuracy, this ambitious novel reflects some unfortunate choices that diminish its power.

First, too-familiar tropes proliferate, for example Sarajevo as multiethnic paradise, music as resistance, grotesquely injured children, raping Serbs, disaffected youths, clueless westerners, and hippie sages. This distances the reader from Rudolph’s fictional universe, which lacks the singular images and nuanced stylistics of, say, Shards (Prcic), How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone (Stanišić), or The Question of Bruno (Hemon).

Further, pacing is uneven. Section 1, the most effective, slowly constructs the rich lives of Jevrem’s family until the siege impels the narrative forward, while section 3, showcasing Jevrem’s escape from the juvenile prison and the transcontinental road trip that follows, moves quickly toward its dénouement. Section 2, the longest, slows to a crawl, lingering on Jevrem’s angst and the repetitive escapades of his disaffected, multiethnic “bastards,” teenaged Bosnian transplants who drink, do drugs, “liberate” goods from haves, and give randomly to have-nots.

Although Jevrem narrates this first-person account, issues emerge about speech modes. While its epigraphs urge resistance to “official stories,” the novel itself appears to deconstruct this notion. For example, the letters and tales of Baka, Jevrem’s Partisan grandmother, who fought fascists as a youth and clings to Tito’s ideal of national unity, embody defiance. Through them she becomes Jevrem’s guide; he frames his account with hers. Yet Baka’s dream conceals the hegemonic power of Tito’s ideology, implicated in the very violence that devastates her family.

In section 2, moreover, his teachers’ doctrinaire platitudes elicit Jevrem’s scorn, while his prison counselor fights his silence with the claims of therapy-speak. Yet Jevrem later admits to conversing with the latter in his head and heeds his English teacher’s praise of prose fiction. Their words enter his arsenal.

Finally, Bastards anoints two groups as truth tellers. Jevrem’s family and friends provide historical context through pro-Yugoslav utterances closer to sociopolitical treatise than spontaneous discussion. Likewise, the trucker “saviors” who transport Jevrem from frigid Canada to paradisiac Los Angeles offer Zen-like pearls freighted with the force of Bakhtin’s “hagiographic discourse.” These voices, given dominance, become Jevrem’s “official stories.”

That those unlikely gurus make Jevrem feel “like a character in a movie, important enough to run into saints and seers” underscores the problem with this interesting but flawed text. Reprising the movement from paradise lost through purgatory to paradise regained, Bastards offers an improbable, unearned happy ending that undercuts earlier attempts at verisimilitude. Its aim exceeding its execution, it resembles less a divine comedy than a well-intentioned Hollywood film.

Michele Levy

North Carolina A&T University