“If We Change the World We Also Change Its Meaning”: An Interview with Syrian Poet Adonis

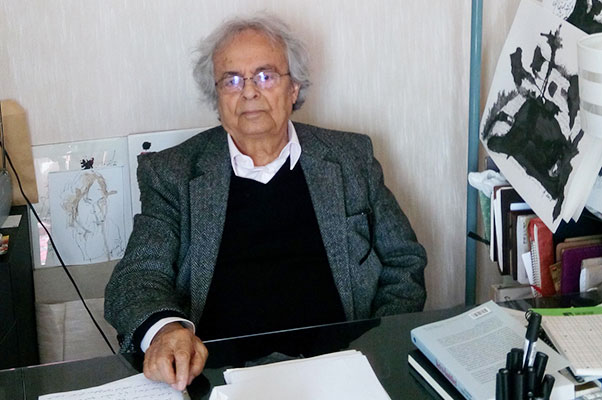

Adonis (Ali Ahmad Said Esber), born in Syria in 1930, is considered the most influential living Arab poet of our times. Due to his opposition to the political regime at the time, he fled to Beirut in 1956, where he played an important role for Arab culture, especially by editing and directing the poetry magazines Majallat Shi’r and Mawaqif with Yousuf Al-Khal, which opened a new path in Arabic poetry in terms of modernism and the evolution of free verse and prose poetry. In 1981 he settled in Paris because of the civil war in Lebanon. This led to new directions in his poetry: reshaping mysticism without religion and the traditional possibilities of Sufism as well as widening and exploring its borders through the surrealist and metaphysical side of individualism. Three of his books—The Songs of Mihyar of Damascus (1961), A Time Between Ashes and Roses (1971), and Al-Kitab (1995–2003)—can be considered milestones of his poetic journey as a revolutionary vision. Since 2002, Adonis has also begun creating images using calligraphy, juxtaposing abstract and surreal elements with original handwriting. He still lives in Paris with his two sisters.

Erkut Tokman: How is your background in Arabic poetry and your oriental side reflected in the West? Do you think that these have had an impact on Western, particularly French, poetry? How do you perceive the East-West dichotomy?

Adonis: For me, East and West have always been notions that are related not to culture and creativity but to politics, the economy, and imperialism. In terms of creativity and creation, in human terms, there is neither West nor East. There is only one creativity, one creation, and one unified world, particularly in terms of the Mediterranean. And as you know, Europe, in other words the West, took its name from a Phoenician goddess from Lebanon. Her brother Cadmus gave the West its alphabet. So at its origin, what we call West and East were born from the same idea.

Having said this, even within a single people there are always different points of view, in the sense that Rimbaud had a radically different vision from that of Mallarmé. For example, in the poetry of Rimbaud there are no significant traces of Hellenistic or Judeo-Christian culture; the East in his poetry represents something else; this is Sufi in that it goes beyond nationalism, race, and religion, and it is surrealist in that it rejects the established values of the West. The difference between one poet and another is not necessarily a national one but a difference that is human and natural. For this reason I like to go beyond this distinction, this kind of Orientalism and Occidentalism; because the human being is one, and therefore the world for him is one. What unites us is not the East or the West but the universe; it is poetry, creation. So by definition and by the nature of creation, the human being is one, and we are all universal.

ET: You speak of how poets such as Abu Nuwas, Niffari, and Al-Maʿarri changed and influenced Arabic poetry. What is your view of Arabic poetry and your own poetry in terms of such change and innovation?

A: I believe that what is known as Arabic mystical poetry, particularly for me and for Niffari, is a vision of the world; it is a way of writing the world, and therefore poetry goes beyond the poem. There are many poems with no poetry. So for me this poetry, this vision of the world, was like a poetic revolution in the Arabic world because this poetry changed the notion of writing and took it beyond the classical rules of prosody, unified it between what we call poems in the classical sense of the word—in other words, rhythmical poetry measured according to the classical traditions—and free poetry, or what we call prose poems. Niffari is a great creator of prose poems. So they changed the way of writing; they added prose to poetry. And after them there was no difference between prose poetry and classical poetry. That’s one point.

The second point is that they changed the notion of identity. The identity born with them was no longer an inheritance but a creation. And the human being creates his identity by creating his works.

Third, they changed the traditional notion of existence, or even the notion of truth. Truth is not only linked to what we see in reality; truth is part of the invisible. Therefore to better understand reality, or what we call truth, we have to make a unity between the visible and the invisible. So we can call the invisible, as the surrealists did, the surreal.

For mystics, this was called al-imla, in other words something that comes to the poet, to the mystic, once he has mastered his body. When he masters his body he feels as though he is part of the light, and therefore of the unknown, and therefore of the invisible.

Fourth, Arabic poetry invented a form of expression that the surrealists called automatic writing. For mystics, this was called al-imla—in other words, something that comes to the poet, to the mystic, once he has mastered his body. When he masters his body, he feels as though he is part of the light, and therefore of the unknown, and therefore of the invisible. He becomes pure light; and in this moment of ecstasy he receives the poetry as one receives a revelation. We call this al-imla or dictation, the universal dictation that arrives in this way. All this was a revolution in the Arabic language and in Arabic writing in general. Unfortunately this is something that is not widely known, even by Arabs, which is why westerners do not know about it. It should be known and recognized, and I hope this poetry will be translated in France.

ET: Your poetry encourages people to question, rage, and revolt against established systems of all kinds in the name of freedom. You are a resistance poet who declares, “I will not surrender to you.” What role do you think poetry has to play in this sense?

A: The function of poetry is not to declare war against institutions, tyranny, religion, etc. Poetry is, by definition, antidespotism, antityranny, and antireligion in the sense that religion is a closed system. I believe that it is rare, even historically, to see a great poet in any language who is a real believer in the traditional sense of the term, particularly in monotheistic religions. So for me, to be a poet is to be antireligious, or rather areligious; in other words, it is beyond dogmatism.

ET: Did your rebellion against the system continue after you settled in Paris?

A: Yes, of course. For me, writing is creating new relationships between words and things, between the word and the world, and by doing so providing a new image of our world, an image that is more beautiful and more humane. To write poetry is therefore to write a perpetual revolution against the reigning powers. It is to revolutionize ideas and ways of seeing things, always with the aim of creating a more humane and more beautiful world.

ET: The answers to the questions that you constantly pose in your poetry are like dust floating in the air; they are both there and not there. This has made you and your poetry so free that you seem to look at the world from a divine place. Could we consider that your poetry has a divine mission to herald the arrival of something new?

To write poetry is therefore to write a perpetual revolution against the reigning powers. It is to revolutionize ideas and ways of seeing things, always with the aim of creating a more humane and more beautiful world.

A: First, to repeat what I have said before, for me there is no distinction between poetry and thought. Poetry is thought, and great thought is also poetry. What I want to say is that poetry surpasses the traditional classical limits of poetry; poetry exceeds the poem. We can find poetry in a novel; we can find poetry in philosophical language. There are many philosophers who were poets, such as Nietzsche or our ancient forefather Heraclitus. So in a way to be a poet is also to be a thinker, because if we change the world we not only change the image or form of the world, we also change its meaning.

Poetry must be a new way of seeing the world, not a horizontal description or narration but a vertical vision.

I repeat: we cannot separate great poetry from thought.

ET: Your poems sometimes blend Sufism and surrealism to create new objects in an imaginary alchemical plane. Is there a religious aspect to these two concepts, or should we simply see this in the context of mysticism?

A: The more profound meaning of surrealism is the idea of passing from the visible to the invisible, surpassing everything that is institutional and imposed on society. And it is a perpetual transgression of everything that obstructs or hinders the total freedom of the human being. In this sense, I find that there is a great deal of affinity between surrealism and mysticism, which is why I wrote a book comparing the two. I said that mysticism was a form of surrealism, as a method and vision against official religion. In other words, I see mysticism as a school of thought, as a school of writing that is beyond religion. If there is a spiritual side to it, this does not interest me. What interests me is the mystical method, and this method is the same as the surrealist method in terms of ecstasy, dictation, or automatic writing, in terms of how to write, how to look at the world, in terms of a range of aspects including identity, the notion of reality, etc.

To repeat, when I speak of mysticism I disregard its religious aspect.

ET: In your poetry there is always a sense of longing for your homeland, a connection to your origins. Under what conditions would you like to return to your country or to the Arab region? What future do you imagine for the Middle East and Syria?

A: In order to push the notion of identity that I evoked earlier a little further, I believe that the human being must live and must belong to the universe, not to an identity that differentiates him from other peoples or other identities. What is human is the identity of a creator. It is beyond nationality, beyond geography, and, I would say, beyond language, too. We are human before we have a language, a culture, or a nation to which we belong. Therefore in poetry we feel that above all we are human, and therefore above all we are universal.

So in a way to be a poet is also to be a thinker, because if we change the world we not only change the image or form of the world, we also change its meaning.

ET: So what does Adonis expect from the future? Are there new things that you would like to do and other things you would like to achieve?

A: [laughs] I can say that I am always in search of myself. I am looking for someone who can tell me who Adonis is and what a future for him is like. But I do what I do for three reasons. First of all, to know myself better and to better understand who I am. Second, to better understand the other; the other is part of who I am. Third, to better understand the world. A better understanding of the world means living your life in a better way. We are only given one life, and so we have to understand it and live it the best we can. Essentially, poetry helps us to live like this, at this level.

ET: Could you tell us about your meeting with the Turkish poet Nâzım Hikmet and your impressions of him?

A: I met Nâzım Hikmet in Beirut; I think it was at the beginning of the 1960s. I looked for the magazine with his photo in it, but unfortunately I couldn’t find the right issue. He was a man I liked very much on a personal level, an adorable man, a gentle and open man who listened to others; these are the qualities of the poet. There is no need to speak of his poetry, which is recognized throughout the world. I greatly admire him both as a person and as a poet.

I read his poetry in Arabic, translated from the French. Personally I prefer that poetry be translated from the original language, but it still gave an idea about his poetry. It is better than nothing. It inspired many people to translate it and read it.

ET: In May, an exhibition of your visual works that combine poetry, calligraphy, and surrealism was held at the Galerie Azzedine Alaïa in Paris. Can we also call Adonis an artist? These are all profound, multidimensional works that require skilled craftsmanship, something that is also reminiscent of your poetry. What would you say about this side of your character?

A: Poetry is a perpetual creation of form and image, so I tried to create, using words, a form that is different from the form of those words. I tried to add to the words the color and physical dimensions of painting. In this sense I do not consider myself a painter; I always think of myself as a poet, and therefore what I do in this field is an extension of my poetry. I use the Arabic word rakima for collage. I prefer this word because it recognizes color and writing at the same time; it is a much better word than collage. For me rakima is a poem but with colors, with lines and forms and with india ink. You could say that it is a more complete poetic form than the simple form that uses only words.

Translation from the French

By Kate Ferguson

Editorial note: The Turkish version of this interview appeared in the literary magazine Varlık in September.