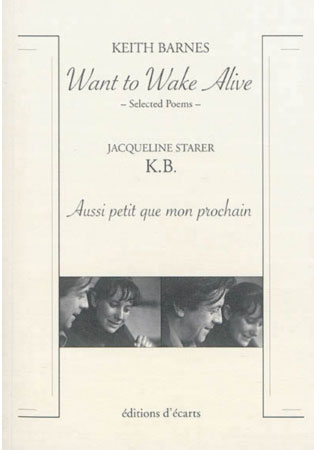

Want to Wake Alive: Selected Poems / K. B. Aussi petit que mon prochain by Keith Barnes & Jacqueline Starer

Helen McPhail, tr. Dol de Bretagne, France. Éditions d’écarts. 2014. ISBN 9782919121175

Helen McPhail, tr. Dol de Bretagne, France. Éditions d’écarts. 2014. ISBN 9782919121175

Born in 1934 in Dagenham near London, Keith Barnes painted at age eight and wrote his first score at age twelve. Having started a promising musical career, he destroyed all his compositions at age twenty-five to focus on poetry. In 1962 he started a nomadic quest that took him from Cyprus to France, Israel, and the United States. He wrote two volumes of poetry, Born to Flying Glass (1967) and The Thick Skin (1971), and three unpublished novels before dying of leukemia in 1969 at age thirty-four. His legacy would have faded to a shadow in war poetry anthologies but for the efforts of Jacqueline Starer, his companion between 1963 and 1969. For the past fifteen years, she tirelessly organized readings of his poems in French bookstores, on French radio, and at international festivals. She published three books about him with the Éditions d’écarts, a small Breton publishing house: Oeuvre poétique / Collected Poems (2003), K.B. Keith Barnes (2007), and The Waters Will Sway: Selected Poems / Die Wasser werden schaukeln:Ausgewählte Gedichte (2010).

Want to Wake Alive is part tribute and part love story. Barnes and Starer experienced love at first sight, a coup de foudre, and were only separated by his mort foudroyante. They lived in constant motion, spontaneously and to the fullest, and brought out the best in each other in spite of the odds. Starer brought sense, stability, and support to his life. He dared her to be creative. She was not just his muse but an equal partner. Her latest book’s structure shows it clearly. Fully bilingual, it features a selection of Barnes’s poems in English, Starer’s own biography of the poet, translated by Helen McPhail, and her own interpretive translation of the selected poems.<

Barnes’s first poems, “Devaluation,” a melancholy reflection on the alienation caused by war, and “Catterick 1954” (International Socialism, Winter 1961), a tale of young recruits, addressed the pain caused by a century of war. He soon adopted a deceptively simple, antiheroic style focused on everyday life. Adopting American English, he used wordplay, neologisms, elliptical phrases, and alliteration. The poem “Try Not to Have Something to Say” shows how he used these techniques to enhance a rich web of cultural references. The poems written during the last year of his life formulate anguished existential questions in a lapidary style reminiscent of John Donne’s. The blank spaces between words represent silent signs of childhood war trauma, postmodern transgression, and self-search. His last poem, “Pencil,” is pure chiseled wit: “As richly colored as the crowns of kings / gold red black as any summer pie / I had pencils like you before / always withdrawing as they draw / who finished up / but stubs / but butts / their ash spilt on pages.”

“Poet-albatross,” as French critic Maurice Nadeau called him, Barnes “never thought I’d cry except it rains so lone” (“God Give Me My Bone Back”). In his quest for innocence, he gave us glittering shards of heaven that challenge us to “want to wake alive.”

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin