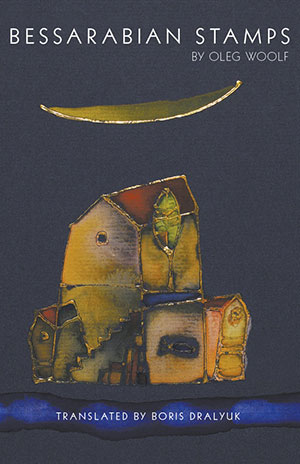

Bessarabian Stamps by Oleg Woolf

Boris Dralyuk, tr. Los Angeles. Phoneme Media. 2015. ISBN 9781939419286

Boris Dralyuk, tr. Los Angeles. Phoneme Media. 2015. ISBN 9781939419286

The poetic proclivity of Moldovan-born Oleg Woolf is everywhere present in his Bessarabian Stamps, a prose work written in a lyrical style, unrestrained in its use of alliteration and allegory (see WLT, Nov. 2011, 52). The book consists of sixteen darkly whimsical “stamps” (most of which are nearly short enough to fit on the back of a postcard) that feel more akin to fables than short stories, each one joined to the next through common characters and thematic concerns rather than storyline or chronology.

While the colorful residents of the Moldovan village of Sănduleni are central to these stories, each remains largely inscrutable. In lieu of standard character development, Woolf details their superficial traits—physical features, occupations, and habits. The clairvoyant Feodasi, with eyes each a different shade of blue, is consulted for advice “as a soothsayer, interpreter, and miracle worker . . . or just in case.” Day after day he sits under a plum tree rereading a treatise on the role of birds in Odessan seafaring. Like the other villagers, Feodasi’s thoughts and feelings remain intentionally obscured, which makes reading Bessarabian Stamps a bit like viewing the negative of a photograph—the negative’s inverted exposure obscures those very parts of the image that would facilitate recognition and understanding of it.

There is an uninhibited joy in Woolf’s writing, and translator Boris Dralyuk impresses with his ability to capture this quality in translation. Invented words are playfully scattered about: “morning’s morninger than evening; . . . . details were separated from the happenchaff along with the wheat”; as are sensory-laden descriptions: stars that “burst, crunched, and crackled over Sănduleni, like a barrel of fermented cucumbers”; and a tempestuous bride who is “like an apple orchard in a May thunderstorm.” Woolf cleverly pairs opposing concepts to convey ironies that are absurd and at the same time hold traces of meaning: “Ever since he grew fat, he’s lost a little weight, and when we meet him, he might tell us that the ailment’s primary symptom is death; and, [t]he firstborn had entered the world so old that knowledgeable people, shaking their heads, tried to reassure her: nothing to it, they said, he’ll fall right into childhood as he ages.” Woolf’s alchemy with words compels rereading to better appreciate his intentional nuances, and I succumbed to it by reading the book straight through a second time as soon as I finished it.

Bessarabian Stamps is not all whimsy and lightness. The cruel, arbitrary grip of fate, which takes the form of a metaphorical, northbound train that transports the villagers into the next world, casts a shadow on Sănduleni. Only Feodasi is immune: “They say a sage has no fate, but the average person receives one along with a name. . . . Feodasi had no fate. His own father couldn’t surmise the meaning of his mysterious name.” As for the fate of Feodasi’s neighbors, only these “stamps” of their lives remain, posted at Sănduleni’s single mailbox and collected in the darkest hours of the night by a guy on a bicycle.

Lori Feathers

Dallas, Texas