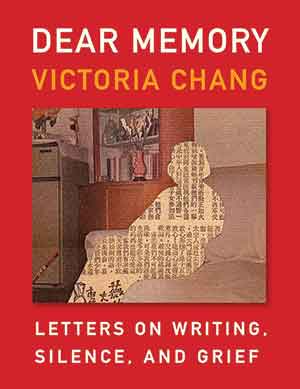

Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief by Victoria Chang

Minneapolis. Milkweed Editions. 2021. 136 pages.

Minneapolis. Milkweed Editions. 2021. 136 pages.

I READ VICTORIA CHANG’S poetry collection Obit (Copper Canyon, 2020) after the death of my father. It was the only book that made sense to me. After his funeral, when his junk mail kept arriving at my house, when I saw his facial features forged in the sharp bones of my own, I turned to the book Chang wrote in the years after she lost her mother to pulmonary fibrosis and while her father’s dementia continued to progress. Obit, as the name suggests, is written in the style of newspaper obituaries and includes obits to “civility,” “approval,” and “language.” It is a spare and stunning book. The form is simultaneously constrained while also holding the keen of raw grief.

In Edwidge Danticat’s The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story (Graywolf, 2017), she describes the dreams she had while her mother was dying from cancer. “In the days leading up to my mother’s death, I would dream of running into my father unexpectedly at cocktail parties,” she writes. Her father would be sharply dressed in the dreams, and they’d talk about how good the party was. “Dreams are sometimes portals of grief,” she observes in The Art of Death, her book that is both an account of her mother’s illness and a work of literary criticism. “Later I would realize that I was dreaming for my mother. In the dream, I was her. I was wearing her dress and it is even possible that I was also wearing her face.”

In Victoria Chang’s latest book, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief, the essayistic and epistolary function as portals of grief. This spare book belongs to a lineage of grief-works that meld personally voiced memoir with literary criticism—Naja Marie Aidt’s When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back, Lara Mimosa Montes’s Thresholes, and Terry Tempest Williams’s When Women Were Birds come, most immediately, to mind. In Dear Memory, the first-person speaker addresses family members, teachers, the body, and even the Ford Motor Company, where Chang’s father was employed. She writes to her grandmother and mother, who have both died. The letters are not nostalgic, solely peppered with fond moments together, but full of curiosity, brimming with questions. The desire to know more after death is poignant, felt, but never sentimental or overwrought. The epistolary functions in Dear Memory as a kind of intimate address. A way to keep the past close and the speaker actively engaged with it.

Dear Memory is a more expansive project than Obit and a more collaged work; it includes many more autobiographical details about Chang’s family. Her mother fled from China to Taiwan with her parents when she was a young girl and then left Taiwan for America when she was in her early twenties. Chang’s parents raised her in a Michigan suburb. Her mother rarely spoke of her past. Over breakfast with another poet, whose mother had left her own country, speaking about trauma and their mothers, both writers observe that their mothers rarely spoke about their pasts to their children and that maybe it was the next generation, their generation, “who will write in response to that history.” Throughout the pages of Dear Memory, letters pose questions to Chang’s parents and grandparents about their lives before her birth. As Kamran Javadizadeh observers in his review of Dear Memory in the New Yorker, “Even the most basic facts about Chang’s family’s past remain mysterious to her: it is only by sorting through old documents that she learns her mother’s birthday, her father’s rarely used American name.” How to mourn such losses? readers are asked to consider. Chang writes, “What form can express the loss of something you never knew but knew existed? Lands you never knew? People? Can one experience such a loss?” In the face of these ambiguous losses, Javadizadeh concludes, “the connection between them is an invention, an experimental grammar.”

Just as my father’s junk mail kept streaming into my mailbox, years after his passing—each new sales offer pleading with the past to answer back—both Obit and Dear Memory refuse to follow a neat chronology. Grief isn’t written in the past tense, these works suggest. Grief is ongoing. Chang writes that memory “isn’t something that blooms, but something that bleeds internally.”

In Jacques Roubaud’s Some Thing Black, the lyric essay he wrote to mourn his thirty-one-year-old wife, photographer and writer Alix Cléo, who died suddenly by pulmonary embolism, Roubaud’s fragments detail the ever-present “not-there-ness” of her—her things, his memories. Dear Memory is similarly ever-present. The ephemera of Chang’s mother’s and grandmother’s lives, all that sticks around after a beloved person has died—their social security card; their marriage license—holds the quality of “not-there-ness.” The book brims with snippets of conversations (Chang had interviewed her mother in the years before her death, and excerpts of their conversation are included). Family photos are placed beside letters. There is a photo of the author and her sister as young girls sitting in a teacup ride; another of her parents, young and beautiful, posing with friends.

“I’m still learning how to make my own chisel,” Chang writes, “but everything I write, no matter how crude, is an experiment with my unfinished chisel.” Maybe memory is the chisel and death is like wood or stone. Memory and language carve, not statues or monuments, but doors and windows and portals. “Maybe our histories can never be fully known. Maybe curiosity is its own language.” I cannot hear my dead father laugh again. Chang cannot know if her mother had pockets in her dress when she left China for Taiwan. But as her work reminds, we can extend our curiosity to the dead. Maybe this curiosity is a form of being with them. The asking of questions answered by silence. Maybe the asking is an act of animation, a way to get close.

Kathryn Savage's forthcoming Groundglass: An Essay, explores topics of environmental justice and links between pollution and public health. Her writing has appeared in the Academy of American Poets poets.org, BOMB Magazine, Ecotone Magazine, the Virginia Quarterly Review, World Literature Today, and the anthology Rewilding: Poems for the Environment.

Kathryn Savage's forthcoming Groundglass: An Essay, explores topics of environmental justice and links between pollution and public health. Her writing has appeared in the Academy of American Poets poets.org, BOMB Magazine, Ecotone Magazine, the Virginia Quarterly Review, World Literature Today, and the anthology Rewilding: Poems for the Environment.

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate link, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!