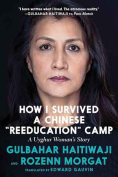

Naming of the Bones by John F. Deane

Manchester, UK. Carcanet Press. 2022. 152 pages.

Manchester, UK. Carcanet Press. 2022. 152 pages.

SECULAR ATHEISTS OR adherents to faiths other than Christianity who admire fine poetry should not avoid reading John F. Deane’s new book, Naming of the Bones—because its content is overtly concerned with Christian subjects and issues of faith—any more than they would fail to admire the art of Leonardo da Vinci in The Last Supper or The Annunciation. The best passages in this 152-page book rise to the highest levels of poetic craft and persuasion.

The title of the book forecasts its architecture and serves also as a multifaceted metaphor for the subjects of the poems. “Bones” are, of course, the most enduring parts of our physical being and the core elements of our supporting structure; they also frequently serve as relics, in this case in early Christianity. Metaphorically, “naming the bones” is the poet’s process of identifying and naming the key “old bones” of the Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Christian tradition (his tradition), the “old bones” of his Christian poet precursors (Irish and English), the “bones” of his own personal history (experiential and familial), and the “bones” of his Christian belief.

Many of the poems in the first portion of this book locate themselves in island monasteries and vicinities, especially those of Iona, Lindisfarne, and Inishmurray, in the times of Aidan, Cuthbert, and Colman, going as far back, of course, as the sixth century. These early figures and places are indeed the old indispensable bones of a tradition that even survived Viking invasions to persist in present times. Deane is not engaged in a history lesson here; there is nothing abstracted or merely “informational” about these poems. They are deeply personal quests to engage—imaginatively, poetically, and spiritually—the roots of his present being, his incarnate being, and “to scavenge here for understanding.”

In the poem “Old Bones,” we read: “the black rocks / slippery with weed and sea-wet. Herring gulls barked / like guard-dogs and a kestrel, / fast as a prayer, flew by. I scaled a rock-trail through thistles / where the testy ghosts // wished to be left in peace. To this abandonment, friars came / centuries after the Christ, to forge / salvation, built rock altars, beehive cells, stone churches, / piled up their cursing stones to keep / women and friends at bay.” There is something of an enforced solitude and discomfort in such a quest, which the poet recognizes and shares: “thunder-light on the sea stack, a monk / in tears, huddled under the cold and the coming dark.” Implicit here is a belief that difficulty must be sought and endured.

In a poem entitled “Triple H,” Deane identifies three of his Christian poetic “bones”: Gerard Manley Hopkins, George Herbert, and Seamus Heaney. Of them he writes: “Hopkins in his long unglamorous suffering, / small snappy man in a misery of muscled language; // Herbert, his consciousness of dustworth, / his tentative but eager treaty of love; // and Heaney, witness to the gracefulness of the frames / of dailiness, enamoured of the possible, the worth // of next-door otherness and the allsorts savouring of words: / these, O God, your dead, your un-mortals.” Common to all is a valuing of humility and love, but in Heaney also a recognition of the extraordinariness of the ordinary.

Deane also spends significant time naming the bones of his spiritual journey, including family members who influenced his spiritual development and stations of experience. One particularly moving poem is part 6 of “Grandfather Ted / John Connors” in the form of a letter from his grandfather. In this poem, the grandfather speaks of a time he came to comfort the poet as a young boy who was experiencing a nightmare and crying out in his sleep, but the grandfather found that he himself was comforted. He had held the boy’s “small, sweet-smelling body” against his own “bruised, old-century self” until he slept, but found “I did not want to lay you down, your being blessing mine. And I felt safe, at last, rescued by an access of love, and the world turned, and I let go of my rage and hollowness.” Here, again, implicitly the Way of Christ is proven best: acts of compassion are themselves salvific.

The poet’s naming the bones of his belief does not flinch at acknowledging difficulties. In the title poem, “Naming of the Bones,” he presents a painful image of a child trapped in a 2017 tower fire in London: “A child appears for a moment, at a window // of the sixteenth floor, a moment only, frantic, waving: // to a not-there-saviour; you? We hurt, my Christ, we hurt. Why is our spittle // hot with bitterness?” But then later he sees Christ at the center of it, hurting. In another poem, he even sees the bones of Christ’s body as it writhes on the cross. Late in the book, in “Like the Dewfall,” he speaks directly to Christ, saying, “You have come upon me, / over decades, entering my heart, stealthily, // like the dewfall. Slaughters, disasters, assaults / burst in on our TV . . . My words, of praise and pleading / —astonished still by your fierce, unmeasured love, / offered against despair and nothingness—fall / like stones, like teardrops, beneath your hurting feet.”

Finally, in a vision in which he speaks with a disciple of Christ, he asks, “How can I sing the Lord’s song / in a dead land?” and is told to trust “your voice, / your words. He is word. Speak him.” This, in the final poem of the book, brings us full circle to at least one raison d’être for the book in hand. We are not far, here, from the vision of purpose discovered by Rilke in his Duino Elegies, something of which Deane is conscious when he quotes Rilke’s First Elegy in his penultimate page: “Ein jeder Engel, I remembered, ist schrecklich; and do the angels fly, I wondered, late and late, across the black night sky, to roost?”

Naming of the Bones is not just a spiritual journey; it is a lyrical one, filled with sonic texturing at the level of song and original figurative language that is never ornamental but always essential. His figures place us precisely in feeling and thought. On a monastic island, “old dusty dogs are chewing on their fleas, and the sea / anciently washes up debris along the pebble strand.” “In the nun’s garden the sisters stand apart, shy birds / on the shore of a pounding sea.” The beauty and unflinching honesty of the language are reasons enough to read this book, but the paradigm of a spiritual quest in which everything is at stake, a quest deliberate and immersive, can give clues and hints about living to us all. (Editorial note: Four of Deane’s poems appeared in the January 2007 issue of WLT.)

Fred Dings

University of South Carolina

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate link, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!