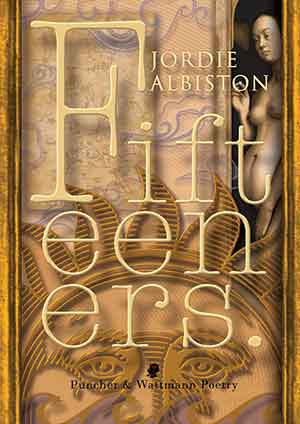

Fifteeners by Jordie Albiston

Waratah, Australia. Puncher & Wattmann. 2021. 98 pages.

Waratah, Australia. Puncher & Wattmann. 2021. 98 pages.

FIFTEENERS IS THE latest stunning installment in this storied poet’s fearless oeuvre, and Jordie Albiston’s book of strangest deformations of the sonnet form traverses “all the life / That an awkward person must go through in / The awkward course toward death.” In the first poem, an ars poetica and apologia, Albiston mimics an Elizabethan diction to reassert the privilege of affect over intellect: “Poetry may / be loved but never thought by love it may / be gotten holden but by thought nay so,” and that love is a paramountcy remains amply evidenced across this poet’s extensive catalog. Her books on love (Element; Euclid’s Dog: 100 Algorythmic Poems; The Book of Ethel) and its multiple modes of atrophy (Warlines; Jack & Mollie [& Her]; Vertigo: A Cantata) suggest that affective modalities—or is it the quest from disequilibrium toward idealized states—have long determined the impetus of this prolific and widely admired writer.

In her 2016 interview with the Hampden-Sydney Poetry Review, Albiston asserts that “the role of form in poetry is that of scaffolding: an exterior chassis for the chaotic interior world.” Amid the manifold discombobulating din, then, in Albiston’s virtuosic hands a poem perhaps provides a chance for the succor and satiety of stability (linguistic qua ontological). For this poet, who died unexpectedly in February of this year (a fact that continues to cause seismic shudderings of grief across the field of Australian letters), “love is / The spring from which we the living must drink.”

Albiston allows readers selectively into her existential precarities, and it is this propensity to make songs from the experience of disquiet, despite everything, that makes her poetry so heartening and simultaneously heartrending: “each dawn I sit / Before this papery reliquary / & it happens— I am like an ancient / Who has swallowed all sorrow & I lift / My hand & I write— I sit here like a // Swallow that has dashed to the ground,” she writes before asking, in some of Fifteeners’ most portentous lines, “what if we could always be un- // Living.”

But these texts never slip by reflex toward the maudlin, never occlusively circle darker tones, and the allusions in this book are often dutifully, delightfully Shakespearean (“if I could library for an age / the sweetness your eyes give my pleasure would / be registered & I would pleasured live,” finding its cognate in Sonnet 18). But often the provenance of these deeply erudite intertexts is harder to place. The spatial breaches located within almost every decasyllabic line resemble less caesurae than enjambments, and therein each line can be understood as containing in fact multiple lines; a panoply of lyric possibility, then. On one hand, Albiston’s Fifteeners share a family resemblance with Shakespeare’s sonnets. On the other, within the lines of these throbbing hymns, her common meter weirdly echoes the lilt of Dickinsonian imperatives.

The result? Each line chimes harmonic as a carillon (perhaps an apt metaphor, given Albiston’s long-standing fascination with bell-ringing). Toward the end of the book, in the poem “Reason,” the poet wonders “how then / can love be defined,” offering several lines later this response: “my love / is not of this world . . . reason / falls like leaves liberating from season.” While we may well each contain an “amnesiac heart,” when transcendentalized under the aegis of this poet’s genius, love can both orientate and propel us into economies of reordered possibility. It seems Albiston has lived within a nonmind logic at once capacious and connective, a utilitarian mode by which ethics (even) might come to be once more radically reconsidered.

Dan Disney

Sogang University

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate link, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!