Art as Inspiration, Liberation: A Conversation with Amitava Kumar

Amitava Kumar—author, most recently, of the novels Immigrant, Montana and A Time Outside This Time—is many things: novelist, journalist, critic, academic. He is also an impressive artist whose drawings and paintings have opened up new “ways of seeing” (in John Berger’s phrase) for him creatively. Here, he speaks about writing and visual art, and how they feed each other in his work.

Anderson Tepper: You’ve incorporated art and photography in your texts at least since earlier nonfiction books such as Bombay, London, New York and A Foreigner Carrying in the Crook of His Arm a Tiny Bomb. What made you decide to use visual imagery in your fiction as well, and does it serve different purposes?

Amitava Kumar: You’re right, you’re right. In those books of nonfiction, at some level, the art was simply doing the work of illustration. Or so it seemed. But in reaching for art—I’m thinking now of a photograph of a pair of earrings sent by a prisoner in Guantánamo to his wife, in my book A Foreigner—I was really trying to do something more with my prose. The aim was to produce a more complex, even more engaged, response in the reader.

Amitava Kumar: You’re right, you’re right. In those books of nonfiction, at some level, the art was simply doing the work of illustration. Or so it seemed. But in reaching for art—I’m thinking now of a photograph of a pair of earrings sent by a prisoner in Guantánamo to his wife, in my book A Foreigner—I was really trying to do something more with my prose. The aim was to produce a more complex, even more engaged, response in the reader.

When used as mere illustrations, pictures serve to root the truth in an identifiable reality. But when you open another kind of space for them, visual materials have this incredible ability to complicate truth without obscuring it. By smuggling art and photography into my fiction, I was playing with the conventional expectation that a picture is an illustration. In some cases, I try to underline the idea that this is a documentary which the reader is encountering, and, in other instances, I almost want to suggest that what they are encountering is something more illegible, as if in a dream.

Tepper: Who are some other contemporary authors whose novels, in your eyes, have juxtaposed art and text in meaningful ways?

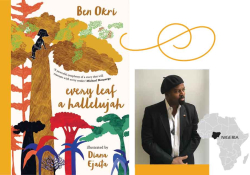

Kumar: For me, much of my interest in images begins with the work of John Berger. I started reading him when I was an undergraduate in Delhi, and I can honestly say it changed my life. My first book, Passport Photos, was an extended homage to Berger. I think of so many other writers who were fans of Berger’s and also his friends: Susan Sontag, Michael Ondaatje, Teju Cole, Ben Lerner. Having said that, let me add that I was also thinking of W. G. Sebald when I was telling you about trying something different in fiction. His use of photographs, for instance, makes the relationship between prose and image more slippery and elusive.

Tepper: Your next book, The Blue Book: A Writer’s Journal, will include your own artwork. What prompted you to begin drawing, and how does your art complement your writing?

Kumar: I have been doing this work for a bit over three years, and The Blue Book is a result of that practice. In late 2018 I was on tour in Canada to promote my novel Immigrant, Montana. When I visited Michael Ondaatje in Toronto, he showed me Berger’s Bento’s Sketchbook. I liked it immensely. At the next stop in the tour, in Vancouver, I bought art supplies and started drawing.

If you are drawing regularly, you are a better observer. That’s one thing. It is my hope, however, that if I continue to do art in a committed way, my regular practice will liberate my artistic practice, that I’ll become looser and freer. Not only in my art but in my writing.

If you are drawing regularly, you are a better observer.

Tepper: What mediums are you principally working in, and how have you developed your technique or approach?

Kumar: I started with rudimentary watercolors and drawings. My point of departure, if I can call it that, was using some sort of a resin over newspaper clippings and then, once the mixture had dried, putting gouache on the newsprint. This was something I did a lot of during the first wave of the pandemic: I was making paintings on the obituary pages of the New York Times. I like gouache more than watercolors because it has a bit more opacity and, of course, isn’t as expensive as oil. More recently, I have also been making drawings on my iPad. It is less messy and quite convenient. The work is easy but never quite as satisfying as the stuff I do on paper.

Tepper: I’m reminded of Berger’s drawings, naturally, but also the watercolors of Derek Walcott.

Kumar: Walcott understood light and shadows. Especially the play of light on water. In the library at Vassar College, where I work, you can also see the watercolors of Elizabeth Bishop. Interesting, vivid work, especially work done in Brazil. Berger’s work, at least in Bento’s Sketchbook, is at once simpler, even cruder, and at the same time somehow more suggestive and therefore artful. After Janet Malcolm died, I discovered her collages. They are wonderful, elegant and sophisticated. It is impossible for me to look at them and not think of the quality of her writing.

Tepper: In Every Day I Write the Book: Notes on Style, you advocate for a daily routine of writing (and walking). How do you fit in both writing and drawing in your schedule?

Kumar: Yes, I say to my students, and to myself, that one must do 150 words of writing every day and at least ten minutes of mindful walking. I’m in London right now, and every day I draw. It’s not easy to find time to do everything, and on some days I’ve been forced to snatch time, making a quick sketch on the Tube when coming back from teaching.

I try not to be tempted, however, to draw or paint first thing in the morning. If I start and then finish a painting, the sense of accomplishment it gives me robs me of the hunger to write. I put a premium on my writing and don’t want it to lack intensity. I prefer to have done some writing and then find relief in putting paint on paper.

Tepper: Have there been scenes of life in London that you’ve been especially inspired to render in your art?

Kumar: There’s a chance I might want to draw some scenes from the literature we are reading. There’s Hanif Kureishi, there’s Sam Selvon. We are reading Zadie Smith’s Embassy of Cambodia. I want to see if there’s a scene I can sketch from the street on which Zadie Smith’s Fatou walks in northwest London. The flat in which I’m staying is close to the Heath. I have already done a few drawings there, but I want to do more, maybe record the changing of the seasons. Looking out of my kitchen window, I have been imagining a series called “London Grey.”

Tepper: Are there works of art that have had an actual impact on your writing in any way?

Kumar: Yes, yes. But let me first ask you a question: Have you read William Maxwell’s So Long, See You Tomorrow? There’s a lovely little description in the book of Alberto Giacometti’s The Palace at 4 a.m. It is as if this work of art is the key that unlocks the psychological mystery of the story Maxwell is telling. I encourage my students to open a conversation in their writing between words and images. One example I use is Wisława Szymborska’s poem “Brueghel’s Two Monkeys.” It’s a brief poem, extraordinary in its imaginative inventiveness, using Brueghel’s painting to create something new.

In what I’m writing at the moment, a novel about a father-daughter relationship, I have put in a painting by the Indian artist Atul Dodiya. While writing an earlier novel, I had on my wall a postcard with a painting by another contemporary Indian artist, Vivan Sundaram. This painting was called Guddo, a shocking and yet beautiful representation of crimes against women by the police or the army in India.

I saw in the painting a lesson about the pressing need to transform experience into art.

Tepper: Can a piece of art inspire a novel? Can a novel inspire a piece of art?

Kumar: Yes. My novel Immigrant, Montana, which was published in India under the title The Lovers, was in conversation with a 1904 painting by Picasso. My narrator has torn from a magazine a painting called The Lovers. The caption in the magazine read: “The drawing was done after Picasso first made love to Fernande.” Picasso was twenty-two at that time, which was roughly my narrator’s age. I saw in the painting a lesson about the pressing need to transform experience into art. Needless to say, I paid good money to buy the rights to have the painting included in my novel.

The other part of your question is something I hadn’t thought about before. Can a novel inspire a piece of art? It is a good question, and my impulse is to say yes. It strikes me that book covers are often paintings inspired by the novel inside. I mentioned my friend Teju Cole; I’ve always been fascinated by the watercolor that appears on the cover of his novel Open City. The painting is of a bird, and, as you know, the idea of the bird, the migratory bird in particular, holds a vital place in the story the novel is telling. The bird on the cover is no ordinary bird; it is a lyrical creature and, even though sitting still, full of movement, an example of calligraphic brilliance. I’m grateful for the fact that a novel inspired that piece of art.

January 2022