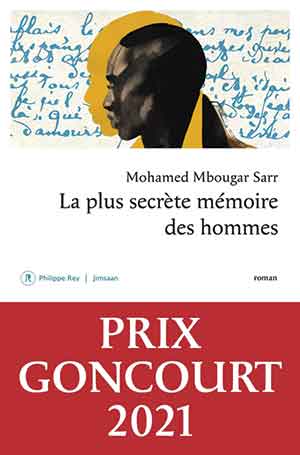

La plus secrète mémoire des hommes by Mohamed Mbougar Sarr

Paris. Philippe Rey. 2021. 448 pages.

Paris. Philippe Rey. 2021. 448 pages.

THE WINNER OF the 2021 Prix Goncourt, France’s most prestigious literary prize, is dedicated to Yambo Ouologuem (1940–2017), the Malian writer whose first novel, Le Devoir de violence, obtained another French literary prize, the Renaudot, in 1968. Ouologuem’s career in the Parisian world of letters rapidly went from very promising to doomed when he was accused of plagiarism. He eventually returned to Mali and led the rest of his life as a semirecluse. Relegated to a form of literary purgatory, Ouologuem and his now-infamous novel haunt Mohamed Mbougar Sarr’s “most secret memory.”

Born in Senegal in 1990, Sarr, like Ouologuem before him, moved to France to study and chose to become a writer. The biographical parallel ends there, since Ouologuem’s career was cut short after his first novel and was largely forgotten, whereas Sarr was awarded the Goncourt for his fourth novel (his first, Terre ceinte, was published in 2014). Sarr was nevertheless clearly fascinated by Ouologuem’s brief period of fame, his sudden fall from critical grace, and his long period of silent expiation. T. C. Elimane, the elusive, ghostlike central character of La plus secrète mémoire des hommes, is patterned after Ouologuem.

Around Elimane gravitates an impressively varied group of characters, most of whom serve as narrative intermediaries between the disgraced author and Diégane Latyr Faye, a young would-be novelist from Senegal now living in Paris who has decided to find out what happened to Elimane after the scandal that reduced him to silence. In his intricately plotted novel, Sarr has modified some elements of Ouologuem’s biography: Elimane is Senegalese, and, most importantly, his notorious novel was published in 1938. The title of that (fictitious) novel, Le Labyrinthe de l’inhumain, provides an indication about the plotline and narrative technique of Sarr’s novel.

The young Faye is on a quest to find and perhaps rehabilitate the much older Elimane. His labyrinthine quest leads him from France to the Netherlands, to Argentina, and finally back to Senegal, where he finds only more stories about Elimane. Along the way, Faye encounters former friends, lovers, or colleagues of Elimane, who provide tantalizingly limited fragments of the older author’s travels and deeds. Faye’s quest becomes an initiatory endeavor, complete with setbacks, periods of self-doubt, and moments of sudden illumination for the younger aspiring novelist. Instead of simply looking for a troubled, intriguing man who suddenly disappeared, Faye navigates through literary history since the middle of the twentieth century. While ostensibly searching for his predecessor and perhaps mentor, he is frequently confronted with his own ambiguous status as an expatriate African novelist writing in French.

Sarr’s novel, replete with apparently digressive subplots and abrupt, often jarring shifts in narrative voice, nonetheless maintains a discernible focus in terms of its broader storyline. As readers are drawn into the minutiae of Faye’s quest, they progressively come to share his questioning of the role and validity of literature during tragic historical periods. This very rich, often innovative novel is highly recommended.

Edward Ousselin

Western Washington University