A Knife, a Thousand Words by Wang Anyi

Taipei. Rye Field. 2020. 315 pages.

Taipei. Rye Field. 2020. 315 pages.

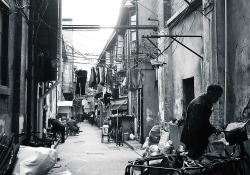

WANG ANYI IS one of China’s major contemporary novelists. Her novels span a wide range of themes, with the most notable being depicting the ordinary, day-to-day experience of the petty urbanites in Shanghai. Her exquisite touch in portraying everyday life continues to be a prominent element of her latest book, A Knife, a Thousand Words, which follows Chen Cheng, a Chinese American chef in his late thirties, as he attempts to navigate his life on a new continent while grappling with memories of loss, the vicissitudes of history, and the search for a fresh start in life.

The novel is divided into two parts. The book’s first half is about Chen’s journey to becoming a chef and his subsequent life in New York. Chen was born in the 1960s in Harbin, a city in northern China. At age seven, he was sent to live with his father’s unmarried sister in Shanghai after his mother died. He stayed there for a few years before moving to Yangzhou, his father’s hometown, to study cooking under a renowned chef. In the 1980s, he fled to the United States seeking his fortune like many others. He traveled to New York after a brief stint in San Francisco, where he began working as a cook in a Chinese restaurant. Guests coming into the restaurant were amazed at the dishes he cooked, as the familiar flavor and texture brought back memories of their past and hometowns. On these occasions, Chen was quiet and spoke only infrequently. He was so absorbed in his reflection even during gatherings of friends. When his father started an unpleasant conversation that brought up memories of the Cultural Revolution and the death of his mother, this lonely man’s secret began to emerge.

The second part of the novel opens with the story of Chen’s mother, whose name is never revealed in the novel. She was a well-educated young woman from a good family in Harbin, married Chen’s father, and had two children. When the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, she initially greeted it with enthusiasm. This enthusiasm waned when she found the practices of the revolution had gone beyond reason. She made her own “big-character poster,” which resulted in her being arrested and executed. Chen hardly knew his mother, who vanished from his life when he was seven. Yet, after a few years, her image began to take shape in his mind as she was posthumously rehabilitated, called a martyr, and her story was constantly featured in the news. How did Chen deal with the pain of his family’s past? He drifted away from his family, became a chef, and began a new life overseas on the traces of anguish and loss.

Chen’s mother is based on a real person, Zhang Zhixin (1931–1975), a political dissident and revolutionary martyr executed during the Cultural Revolution for openly challenging Mao Zedong’s ideology. Wang Anyi does not attempt to explain the martyr’s story in-depth, nor does she try to create a historical narrative. Instead, she invites the reader to contemplate what impact the revolution might have had on people’s ordinary, daily lives. At the end of the novel, Chen returns to Shanghai to attend his aunt’s burial. The familiar surroundings he had left behind bring back memories of his boyhood even more vividly. For the first time in his life, he does not avoid the past but instead embraces in its entirety.

Laura Xie

Virginia Military Institute

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate link, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!