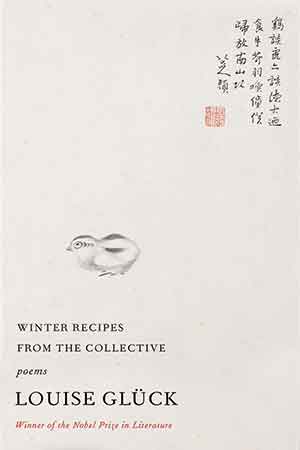

Winter Recipes from the Collective by Louise Glück

New York. Farrar Straus and Giroux. 2021. 64 pages.

New York. Farrar Straus and Giroux. 2021. 64 pages.

LOUISE GLÜCK HAS been the recipient of nearly every award recognizing a poet’s craft. In November 2020 she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. In her acceptance speech, Glück expressed the desire to continue to “honor the intimate, private voice.” Her fourteenth, latest work, Winter Recipes from the Collective, vividly resonates with this theme and embodies a transformative quality of life that is also entwined with the concept of stillness.

The collection’s understated and sparse cover resembles such stillness and deserves some explanation. It exhibits a group of paintings known as the “Album of Pheasants” by the enigmatic seventeenth-century poet-artist Bada Shanren, whose own work contains similarly nuanced threads of restraint and allusiveness. After the fall of the Ming Dynasty, Bada Shanren retreated to a reclusive life in a Daoist monastery. His cryptic inscription appearing on the cover of Glück’s new collection, written when he was in his old age, suggests the emptiness of political rhetoric. It concludes with a seal that indicates how one can only gain true spiritual immortality and enlightenment by withdrawing oneself from worldly possessions. This philosophical connotation finds its parallel in the glowering, humanlike expression of the chick in ink, which appears in monochrome and which, while deceptively abbreviated and ingenious, is imbued with a sense of stillness and quietude.

Glück’s cover sets the tone for the entire collection of fifteen exquisitely written poems, all of which display not only placidity and minimalism but also psychological depth. Reflecting the subtleties and intricacies of human relations, the poems converse with one another in dialogic and narrative forms. The first poem in the collection, simply titled “Poem,” opens with the surreal image of a couple watching a boy and girl eating wild berries from a dish “painted with pictures of birds” and then flying away. The couple desires the same kind of flight but can only descend in “downward” motions. They eventually accept that this world is more “beautiful than the last.” This opening poem echoes the sentiment of the cover’s chick that quietly comes to accept one’s own ability in life.

The rest of the collection’s poems also center on transient, elegiac interactions. These occur between, as examples, two sisters; parents and children; teacher and student; concierge and client. Readers witness how the events unfold in these disparate exchanges and imagistic snippets between individuals about such haunting topics as death, loss, and regret, each of which conveys the difficulties of life. Every relationship oscillates between the dualistic tensions of assertion and ambiguity. However, toward the end of nearly every work, the narratives are abruptly suspended, unfinished, and are seemingly replaced with a recurrent ambience of ascetic emptiness in which beginnings and endings cross each other.

This notion of circularity complements the ancient Chinese wisdom that appears at the end of a few poems in this collection. For instance, in “The Denial of Death,” the speaker alludes to the philosophical adage of Daoism: “all things flow, like the empty cup in the Daodejing – / Everything is change, he said and everything is connected. / Also everything returns.” These phrases underline how the natural order manifests the unceasing returning of all things back to their beginning. In Glück’s poems, the individual is to conform to the natural rhythm of the cosmos by “going with the flow.” Glück seems to suggest that one can achieve inner peace and stillness by embracing life’s transformations.

The poem entitled “Winter Recipes from the Collective” is a four-part parable that further encapsulates such transformative qualities of circularity in human labor. It begins with an elderly couple undertaking “a time-consuming project” that involves gathering and fermenting mosses as the snow falls. These untidy mosses are then transformed into bonsai. Such a transformation is a miniature representation of natural inharmony and simplicity. The final part seems to invoke how the bonsai unassumingly blossoms into part of the arboretum in December, “the month of darkness.” The collective human efforts enable the survival of nature to undergo this notion of constant changes.

The collection urges us to return to the poems throughout, considering the transformations they offer. They urge us not only to read slowly and carefully but to read repeatedly, and to circle back and reconsider them. This thought links us back to the cover—and another voice (that of Bada Shanren) being “recycled” and transformed. Even though many of the poems herein had been published in other literary magazines, these poems, too, have been “recycled” and appear here transformed because of their appearance in a new collection that, taken as a whole, offers something new and yet something “old” too: the persistent intimacy of human voices over time. The end of the collection feels as much like an ending as it does a beginning.

Kent Su

Shanghai International Studies University

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate link, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!