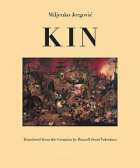

Kin by Miljenko Jergović

Brooklyn. Archipelago Books. 2021. 920 pages.

Brooklyn. Archipelago Books. 2021. 920 pages.

KIN, BY MILJENKO JERGOVIĆ, is a behemoth of a book: 920 pages long and covering more than one hundred years of history. Jergović, one of the most recognized Croatian and Bosnian writers, creates an epic account of his family’s narratives and consequently explores the complex past of Bosnia and its region, marked by the First and Second World Wars as well as the most recent Bosnian war, which often left his family members and his countrymen disoriented, confused, and despondent. Detailing his family’s successes and failures, Jergović repeatedly points out the irony associated with not only the war of the 1990s but almost any conflict in the territories of the former Yugoslavia: in a country in which the clashes were ethnic in origin, and in which one’s side in a war was often associated with one’s ethnicity, hardly anybody is not of mixed origin. Jergović’s family is that of kuferaši, nonnative to the region, middle class, moved to Bosnia from different parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire under the reign of Franz Joseph. Named after the German word for suitcase (koffer) that Russell Scott Valentino in his excellent translation cleverly does not translate into English, kuferaši are seemingly transient and never fully adjusted, wherever they are.

Jergović focuses on his mother’s side of the family, the Stublers, whose history is summarized in the short, opening chapter and repeatedly revisited in the rest of the book, in an attempt to make sense of his own identity, culture, and complicated family relationships expressed in many Germanic, Romanic, and Slavic languages. The lineage starts with Jergović’s grandfather, an ethnic German from Banat who was transferred from his cushy railway position in Dubrovnik, Croatia, to Sarajevo, Bosnia, as punishment for supporting a strike in the 1920s, and includes a decision to send Jergović’s uncle to join the Nazi army in 1942 in an attempt to save his life. The uncle is killed, which has long-reaching emotional and psychological consequences for the family whose members are also Jewish, leftists, fascists, and communists: “In my case, or rather, in the case of my family, . . . we were Bosnian Croats whose identities were marked by the Slovene, German, Italian, and rare other nations of the former monarchy. If there had been no Austro-Hungarian empire, I would never have been born, the parents of my grandparents would have never met. . . . In this sense my birth was, from before the beginning, a political project.” In 1993 Jergović left Sarajevo under siege and moved to Zagreb, Croatia, where he still resides, reinforcing the notion of the kuferaš identity of his ancestors but also implying that his family’s chronicle has culminated with him.

Autobiographical in nature, Kin functions as a metaphor for a region that has been swept by historical and political forces. More significantly, Jergović mythologizes his family’s history in the manner of Thomas Mann, for example, whom he often mentions in the text, while arguing for its veracity by including family photographs and documents. Writing about Sarajevo and its geography, Jergović delivers a nostalgic, angry, and beautiful tribute to his hometown in “Inventories,” but the most effective of the seven chapters is “Mama Ionesco: A Report.” The section is an emotionally charged examination of Jergović’s problematic relationship with his mother, whose lifelong depression and coldness toward her only child is rooted in a family trauma, caused by a desperate and failed effort to manipulate the kuferaš destiny.

Damjana Mraović-O’Hare

Carson-Newman University

When you buy this book using our Bookshop Affiliate link, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!