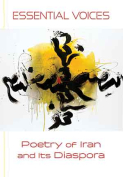

Essential Voices: Poetry of Iran and Its Diaspora

Grinnell, Iowa. Green Linden Press. 2021. 350 pages.

Grinnell, Iowa. Green Linden Press. 2021. 350 pages.

ESSENTIAL VOICES: Poetry of Iran and Its Diaspora brings together 130 twentieth- and twenty-first-century poets and translators. It’s a collection that lends itself to at least two kinds of readings, both hinted at in Christopher Nelson’s poignant editor’s note. The first, more obvious, begins with the assumption that Iran, in the sense of both the modern Islamic Republic and the ancient civilization with pre-Zoroastrian roots, possesses a coherent body of contemporary poetry. According to such a reading, the book collects poets who voice the essence of Iran, whether in Persian, as with the majority of the translated selections (although selections from Kurdish, Azeri, Swedish, and German are also included), or in English, as in most of the diaspora poems. Listening to these Iranian voices carries direct political implications. Read this poetry, the argument goes, to turn the tide against murderous sanctions or to halt hawkish officials on their strut toward all-out war. Reading Iranian poetry, in other words, might help dissolve the hostilities between us and them.

In the second reading, it’s not so much the Iranian identity of the selected poets that demands attention as the fact that they speak in poetry at all. According to this reading, poetry traverses borders and cultures to voice the essence of human existence. Instead of breaking things down, poetry summons us to new, previously unimagined worlds, acquaints us with the not already known, invokes in us sensations not already felt. You could say the same about all art, of course, but what distinguishes poetry is that it operates in language, which is to say the same medium as rhetoric, the same raw material as presidential addresses, military manuals, and immigration forms. Poetry’s best surprises come when it shows us how the same language through which we demarcate and compartmentalize the world around us can also allow us to image our worlds anew. For example, I start by dividing a book into two kinds of reading, but a visionary poet like Simin Behbahani returns me to my senses, declaring that “the world divided by a line is a dead body cut in two / on which the vulture and the hyena are feasting.” There are no mutually exclusive pairs here, no thinking that needs reduction to binaries. “The world,” Behbahani reminds us, “is shaped like a sphere.”

Indeed, Essential Voices covers a spectrum of poetic sensibilities and offers surprises at every turn. The collection includes some of the most visible figures from modern Persian poetry. Among them, I was pleasantly surprised to encounter Mehdi Akhavan Sales’s poem “Winter,” which has long been a favorite among Persian speakers. The poem’s explosive fusion of classical diction with mid-twentieth-century idiom has always struck me as untranslatable. But Fayre Makeig offers one of the best efforts at translation yet—and many have tried before—carrying echoes of Akhavan’s inimitable voice in his opening lines: “They will not answer your salaam, their chins tucked in collars. / No one wants to raise his head / to answer and acknowledge friends.” Other giants of Persian poetry are represented as well, Nimā Yushij, Forough Farrokhzad, Ahmad Shamlou, Sohrab Sepehri, and Behbahani among them. Readers with the Persian already in mind might notice how much the individual translators vary in their interventions and inventions; first-time readers might be enticed to learn more about these icons from Persian verse.

Lesser-known Persian poets like Bijan Elahi and Bijan Jalali appear in the book as well. Their teams of translators, Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Gould in the case of the former and Aria Fani and Adeeba Shahid Talukder in the latter, have made great strides toward bringing the poets to life in English and, in doing so, reintroducing them to Persian readers. And there are emerging voices like Mansur Owji’s, who, in Daniel Rafinejad’s translation, reminds us of poetry’s more perseverant pursuits: “The stone’s silence is so beautiful under indigo. / The stone’s silence so majestic, in a thousand years / the stone’s silence . . . / the stone’s silence will mean me. / (The stone’s silence.) / Speech will mean you, / and poetry will mean speech in stone.”

And just as the Persian poets in the collection vary in their recognizability, so too do the diasporic voices vary in their engagement with and stature within the poetic traditions of the countries to which they or their parents immigrated. There’s Solmaz Sharif, for example, who, by any institutional or cultural measure, writes some of the best American poetry today. Listen to her poem “Look,” with its unforgettable opening salvo (“It matters what you call a thing”) and its litany of lines beginning “Whereas,” and try not to hear echoes of Emily Dickinson. Or hear the ghosts of America present and past in Jahan Khajavi’s entertaining queer poetry whispering through lines like “We are as blind as an old painter spun in your spell, lo / & beholding tight as the Pullman bumps over cent’ries of cruisin’.”

Some of the Iranian American poets in the collection perform their identity more self-consciously. Several poems, for example, share their speakers’ feelings of estrangement during the hostage crisis of the early 1980s and their ensuing struggles to dissociate themselves from images of angry Iranians on the nightly news. A younger generation of poets, having come of age in the wake of 9/11, gravitates more toward Muslim aspects of their Iranian American identity, although their poems often brand themselves with an unvariegated, globalized version of Islam that seems to have more to do with American cultural references than any kind of lived spiritual or devotional practice. I am thinking here of the many poems that regenerate images of headscarfs and turbans or proclaim knowledge of rudimentary theological traditions like the “five pillars” without mentioning that said tradition is anathema to the Shiism practiced by the overwhelming majority of Iranian Muslims, or that riff off recognizably “Muslim” (though, again, not especially Iranian) tropes like “the ninety-nine names of God.” The appropriation of a Muslim identity in these poems may bear some surprises for readers who only know Islam from what the most Islamophobic agents of American empire would have us believe.

For me, though, I encountered the best surprises in poems like Reza Baraheni’s “Daf,” which plays with the form and sounds of the daf, a tambourine-like drum. Stephen Watts’s co-translation with the author struck me as itself untranslatable, the words melting into one another and reemerging transformed: “Now night will never sense silence again / and after these circles of turbulence / I’ll not sleep for a geology of un-numberable years / Here night swells on rim edges of drums and bells— / the daf’s white moon.” The impossibly poetic English of the translation sent me to the internet to discover what was going on in the Persian. There, I encountered several easily found videos of Baraheni performing the original poem and was amazed to hear just how closely the English follows the Persian in structure and form, even with all the inventiveness in translation. But you don’t need any knowledge of Persian to appreciate the sound qualities of Baraheni’s performance. Give it a listen and, if you enjoy that, you can continue on, as I did, to videos of musician Mohsen Namjoo performing the same poem. Namjoo breathes his own life into Baraheni’s words, pounding the words’ rhythms off his tongue and lips at breakneck speed while an orchestra carries the tune. It’s a performance well worth discovering and easy enough to find.

In the end, it’s that encounter with the unexpected that makes poetry endure. If there is a thread running throughout all the poems in Essential Voices, which is to say throughout all poetry, it is their pursuit of a discovery through language. Poetry gives voice to those essences that lie beyond whatever distinctions we might draw between self and other. Or rather, poetry is the voice of discovery and self-discovery. After the passports have expired and the flags faded into obscure relics of some forgotten identarian past, it is only the voice, to quote the eternal Forough Farrokhzad, that remains.

Samad Alavi is senior lecturer of Persian at the University of Oslo. He has published a number of essays and reviews in journals including WLT as well as translations of contemporary poetry from Iran.

Samad Alavi is senior lecturer of Persian at the University of Oslo. He has published a number of essays and reviews in journals including WLT as well as translations of contemporary poetry from Iran.

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate link, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!