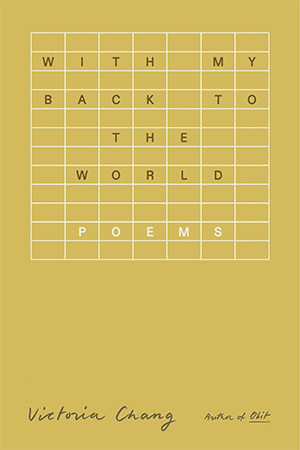

With My Back to the World: Poems by Victoria Chang

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2024. 112 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2024. 112 pages.

The poems in Victoria Chang’s With My Back to the World are written in dialogue with the abstract expressionist paintings of Agnes Martin. Ekphrastic in nature, Chang’s new poems are printed alongside collaged imagery and time-stamped early poem drafts, inspired by conceptual artist On Kawara’s Today series. The speaker critiques and discusses Martin’s artwork in both straightforward prose and lyric reflections. New writing centers Chang’s major themes across earlier works of poetry and essay: grief, tenderness felt for family, teachers, and, equally, more abstract affective states, such as silence.

While this is a quieter book than Chang’s earlier works, it remains psychologically astute and generous in its focused attention on the work of another artist. Martin gained recognition in the male-dominated New York City art world of the 1950s and ’60s before moving to northern New Mexico’s high desert. Throughout her career, Martin painted six-by-six-foot canvases covered with geometric schemes in warm and cool palettes. She was especially known for painting detailed grids. In the poem “Untitled #5, 1998,” Chang quotes Stéphane Mallarmé: “Paint, not the thing, but the effect it produces.” The speaker looks at the grids Martin paints and sees “the wet blue wound”; sees shapes that “turn into memory”; and offers to the reader not the thing, but the effect it produces.

In approach and sensibility, Chang’s latest recalls Fred Moten’s scholarship about ekphrastic translation. From Moten’s 2004 interview titled “Words Don’t Go There”: “I listen to some music that I love and it inspires me to write a poem. My poem is not going to be that music. And if my poem only attempts to imitate that music, it’s not going to be worth a lot. But if it’s an attempt to get at what is essential to that music, perhaps it will approach the secret of the music, but only by way of that secret’s poetic reproduction.” Pencil lines are a prominent feature in Martin’s work. By way of “poetic reproduction,” a pencil line is like a poem in the same way that a memory is like a poem—felt, and yet capable of influence by time and another—able to be distorted, eroded, changed—and yet always holding the instant of invention. Perhaps a pencil marking on a page retains the presence of its creator like a poem does, in sensibility and gesture. The speaker looks at Martin’s artwork and thinks: “Agnes’s lines desire to touch each other, but never can. / Depression is a group of parallel lines that want to touch, but never can.” Through collapsing the distance between the speaker’s own experiences of depression and observation of Martin’s signature pencil lines, Chang’s poem approaches the secret of the image but does not reproduce it. “This resembles a life, / each day a mark on canvas.” Chang’s poems seem to be interested in Martin’s artwork for what this artwork suggests, especially when concerning the passage of time: “Suddenly, I remember that there is a middle / of the day. I’ve spent years / considering the beginning / or ending.”

Author of six previous books of poetry and recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Chowdhury Prize in Literature, With My Back to the World once more puts forward Chang’s genius for deploying formal constraint in order to explore aspects of personal identity and emotion. Obit (2020) is a book of accumulative, elegiac poems that take the form of newspaper obituaries written after the death of Chang’s mother; Dear Memory (2021) was Chang’s essayistic and epistolary work on similar themes (see WLT, May 2022, 55). In Dear Memory, the speaker writes letters to the living, the dead, and to silence itself. Across various books, Chang frequently works within contained forms to write about what cannot be easily contained: death, and the ongoing project of living in the face of great personal loss. However, earlier works are more direct in their exploration of autobiography. In Dear Memory, for instance, Chang writes about her mother, who fled from China to Taiwan with Chang’s grandparents when she was a young girl and then left Taiwan for America in her early twenties. Chang was raised in a Michigan suburb, and this work delves into firsthand reflections as part of its major project.

Many of the poems collected in With My Back to the World similarly center aspects of the speaker’s identity that are personal, social, and political. On gender violence and Asian American identity, the poem “On a Clear Day, 1973” references a shooting that occurred in Atlanta in which Robert Aaron Long killed eight people, including six Asian American women. In “Untitled #12, 1981,” the speaker observes: “Agnes must have wanted me to see innocence or happiness / when looking at this painting. But all I see is the gathering / of pink at the bottom. For every woman, there is a man who / is nearby . . . I can’t look at the window / without thinking man. Or kidnap. Or knife.” In “Happy Holiday, 1999,” the speaker notes that: “Surveillance is vertical. War is vertical.”

Whether writing about her family or the work of Agnes Martin, Victoria Chang’s poetry is always extending outward. “When I look at the 16 blue strips, I too love the whole world.” Martin’s paintings become a mirror reflecting not the self of the speaker per se (but surely also this), reaching wider. “My error was to become what / I wanted to be, not its tone.” Poem to poem, Martin is a presence and a reflection; through her presence, the speaker externalizes internal psychological and emotional states. What a gift to the reader, this invitation to press outwardly and inwardly at once as if both reaching and grasping simultaneously, as if holding hands.

Kathryn Savage

Minneapolis

![The cover to [...] by Fady Joudah](/sites/worldliteraturetoday.org/files/styles/backissue_small/public/Joudah.jpg?itok=HZO1_68A)