Ochre and Rust: New Selected Poems by Sergey Gandlevsky

Grinnell, Iowa. Green Linden Press. 2023. 114 pages.

Grinnell, Iowa. Green Linden Press. 2023. 114 pages.

The central figure of a six-line 1994 Sergey Gandlevsky poem is a writer, standing alone, disheveled and jittery, preparing “to howl” into a frigid “northern wild.” In the concise setup of this short work, many of Gandlevsky’s lyrical hallmarks arise: inevitable solitude, a sensitivity for the low and the unwashed, a masculine roughness tempered by glimmers of traditional form, self-conscious refusal of prescribed paths. In this poem’s iteration of such themes, especially with the insistent classical pulse of the Russian original’s amphibrachs and direct rhymes, the poet comes as close as ever to fitting his self-image into that of the Golden Age tradition of the exiled poet-prophet established in Russia by Pushkin (and variously reframed in eras since by writers ranging from Khlebnikov to Brodsky).

For Gandlevsky, however, the affiliation with this prophetic figure is all setup: once he has described the outcast poet’s initial movements through the wild borderlands that (in keeping with, say, Lermontov) are the echo chamber for God’s word, he slyly ends the poem, seemingly just as it was getting started. The final line—which starts by painting an expectant and expected firmament where “stars chat with stars”—is broken by a caesura and ends with the sudden, violent interjection, “closed quotes.” The dalliance with the Romantic oracle’s mantle appears as a performance, sincere or otherwise, with Gandlevsky signaling that he is only inclined to carry the act so far. Ending in this way suggests the distinct abruptness of unexpected mortality, which abbreviates and recontextualizes a life as easily as it does the poetic utterance.

Gandlevsky’s poems of the early and mid-1990s read as an essential anchor of pathos for a body of work habitually preoccupied with time and its passage, to age, aging, interrelations of ages, and, ultimately, to death. The nineties were a time of multiple turnings in this regard for Gandlevsky: the country of his birth had just been dissolved and reformulated, he had just turned forty and was acutely aware of what he would later call his “elderly youth,” and—most distressingly—he had recently been diagnosed with a brain tumor, which seems to manifest in the above poem as a “tic in [the] cheek” or in another poem as a “loud ticking everywhere.”

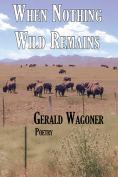

Merciless time does tick insistently in all of Gandlevsky’s highly rhythmic work; it is the beam that runs through his sharp, nostalgic evenings and blurry, hungover mornings. And his early and insubordinate poems of the 1970s and ’80s wind the clock both backward (“Long ago, we wandered in on the festival of death”) and forward (“I’m still far from being a patriarch”), while often attempting to freeze a moment of clarity in a kind of recursion. The briefly lived poetic brotherhood he formed at university was called, after all, Moscow Time. At the other end of his oeuvre, the heavily elegiac poems of the twenty-first century (“Around the yard, old age ambles”; “Bright ochre and rust delight these old eyes”) tend to make time’s patina the aesthetic precondition for perception.

Ochre and Rust: New Selected Poems, prepared by translator Philip Metres, presents a full chronology of Gandlevsky’s career with poems ranging from 1974 to 2016—though the arresting decision has been made not to attach dates to any of the poems. The arrangement of the poems in four untitled sections is a reminder that even outside the press of time, the poet’s unwavering nonconformity and reprocessing of familiar forms is as much an existential position as it is an aesthetic or political one. The labor that Metres (who has collaborated with the poet since the nineties) has put into this loving anthology is immediately apparent. His subtle, dynamic translations are the product of decades spent crafting English versions of Gandlevsky’s idiomatic and idiosyncratic Russian; they are delicate and brisk when the original is and then brusquely vulgar, matching the poet’s characteristic style. Along with his very thorough introductory essay, Metres’s translations offer an excellent introduction for nonnative speakers to one of the major voices of late- and post-Soviet Russian poetry.

Ochre and Rust might also be seen as an update to a previous edition of selected Gandlevsky poems, A Kindred Orphanhood, a 2003 dual-language edition that also featured translations by Philip Metres. In Ochre and Rust, many of these translations appear largely unchanged, but some have been heavily revised and honed, to great effect, such as in 1978’s meditation, here titled “At last it’s snowing. Yes, some Russian words” where previous reflections on life in “the country” have now become ones on living in “a certain country.”

That Gandlevsky is still actively composing poems, and that Metres continues to translate them, is in some way a refutation of life’s foolish ephemerality, the awareness of which has saturated the poet’s practice. This persistent impulse is key: that, despite death, the poet “[sits] up to write, / Startled [. . .] / In the middle of a dark night.” If time allows, perhaps English-language readers may enjoy—in another fifteen years or so—the next new selection from Gandlevsky’s body of work.

Dustin Condren

University of Oklahoma

![The cover to [...] by Fady Joudah](/sites/worldliteraturetoday.org/files/styles/backissue_small/public/Joudah.jpg?itok=HZO1_68A)