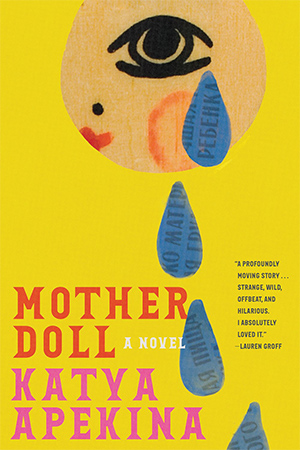

Mother Doll by Katya Apekina

New York. Overlook Press. 2024. 308 pages.

New York. Overlook Press. 2024. 308 pages.

Katya Apekina’s Mother Doll is the strange, visceral story of Zhenia, a Russian American living in Los Angeles, whose marriage crumbles after Zhenia learns she is pregnant. While navigating the early stages of her pregnancy, Zhenia also receives a phone call from Paul, a psychic medium who begins channeling the spirit of Irina, Zhenia’s great-grandmother. Meanwhile, Zhenia’s grandmother, Vera, dies, further complicating Zhenia’s life and her already tumultuous relationship with her mother. As ancestral trauma swamps Zhenia and Irina’s spirit becomes more and more unrelenting in its communication, Zhenia encounters the Russian Revolution’s barbaric background and history, and she grapples with how her former homeland’s sociopolitical upheaval influences her life in America.

At a time when former Soviet nations are decolonizing their literature, art, and everyday lives from the grips of Russian influence, Mother Doll serves as an intimate exposé of brutal events that completely transformed a nation and society and gave an authoritarian regime seemingly endless power and overreach. A diverse cast of Russian ghosts make appearances in Irina’s communications with Zhenia and Paul, each representing a small facet of the revolution. Disillusioned with the tsar and a system that oppressed the common worker, characters like Boris, a former prisoner from Siberia, and Olga, a grief-ridden student, become poster children for the communist ideology. Others, like Hanna, Irina’s Jewish cousin, represent a faction of society that, no matter what system of government replaced another, would always remain ostracized and discriminated against. Nonetheless, as readers traverse Petrograd’s streets where protests rage and violent bombings disrupt everyday life, readers also see how quickly a system that promised socioeconomic equality quickly devoured many of its firmest supporters. Thus, beneath Zhenia and her family’s traumatic story, readers discover a carefully posed history lesson relevant to today’s current events.

While Mother Doll is an exploration of events that not only reshaped Russia and Europe but also the globe, it also takes a clinical look at female agency. Inherently, it is a novel about individual choices, but more so, it is a novel discussing the choices females must make in oppressive systems. This is most apparent in Irina’s story. Irina is quickly swept into the revolution’s dramatic events because of her association with people like Boris and Olga. Readers see that her agency and choice are eroded, especially as Olga forces Irina into situations where Irina must undertake tasks like protecting the bombs Olga manufactures in Irina’s bedroom.

Another stark moment for readers is when, once again, Irina becomes Olga’s puppet. When Olga offers to help Irina escape an increasingly violent Russia, Olga insists that she can only help Irina and not Irina’s young daughter, Vera. Irina is forced to make a decision that determines the course of her family’s future generations. Readers see how this decision influences Zhenia’s own story. As Zhenia’s husband—adamant that he does not want a child—grows increasingly upset with Zhenia for deciding to not abort their baby, Zhenia makes choices that sculpt her present and her future as well as her baby’s: she suggests that she and her husband break up, and as the divorce is finalized and baby Vladimir arrives, Zhenia’s relationship with her mother, as well as her new friend Chloe, transform Zhenia’s life into something she never could have predicted.

One cannot read Mother Doll without noticing how the genius of Apekina’s narrative structure creates a ghostly tone throughout the novel’s entirety. Hauntingly, one narrative ebbs into another, reinforcing the concept that generational trauma is inescapable until one consciously makes the decision to break its perpetual cycle. In this, Zhenia’s story is necessary and inspiring, and as the novel opens discussions about the ever-changing meaning of family and home, the novel establishes itself as one of the most important pieces of Soviet émigré literature to emerge in quite a while.

Nicole Yurcaba

Southern New Hampshire University

![The cover to [...] by Fady Joudah](/sites/worldliteraturetoday.org/files/styles/backissue_small/public/Joudah.jpg?itok=HZO1_68A)