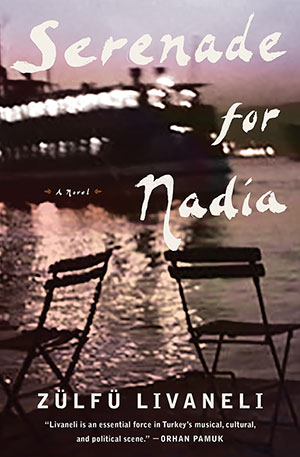

Serenade for Nadia by Zülfü Livaneli

New York. Other Press. 2020. 402 pages.

New York. Other Press. 2020. 402 pages.

IN HIS LATEST BOOK available in English, translated lucidly by Brendan Freely, prolific Turkish author, musician, and counterculture icon Zülfü Livaneli novelized the infamous 1942 Struma disaster, when at least 769 innocent Jewish refugees drowned in the Black Sea due to complicit negligence by the governments of Turkey, Romania, Britain, Germany, and the Soviet Union.

In 2008 Turkey became an observer nation of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA). Since the 1980s, neoliberals in Turkey have aimed to improve relations with Western allies, particularly the United States. By paying lip service to the Holocaust, Turkey shirks the Armenian Genocide and crimes of humanity against Kurds.

Many critics, such as writer Rıfat Bali and academic Corry Guttstadt, have exposed the official line of neutrality and righteousness that is continually forwarded by the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. But the government of Turkey is not solely responsible for maintaining a problematic status quo. A number of books and films have toed the mainstream line. The novel Last Train to Istanbul (trans. John W. Baker, Amazon Crossing, 2013), by Ayşe Kulin, portrayed Turkey as a safe passage for Jewish refugees fleeing to Palestine during World War II. Turkish Passport, by filmmaker Burak Arliel, praised Turkish diplomats for saving Jews under Nazi occupation. These works ignore history. Jews in Europe, even if Turkish citizens, were largely unwelcome in Turkey during the Nazi era.

Livaneli, despite writing a touching novel about the 1942 Struma disaster, has acted against his image as a leader of political protest. In 1997 he led a crowd of five hundred thousand in song demonstrating against Turkey’s tradition of military coups. He himself lived in exile in the 1970s and endured government bans against his books and music.

Serenade for Nadia, originally published in Turkish as Serenade in 2011, is part of a wave of apologist cultural work that positions Turkey as sympathetic to European Jewry. Yet, where others would have altogether dismissed broader themes of minority struggle against racism, xenophobia, and demagoguery, Livaneli took a critical, reflexive approach to the novel.

The lead, Maya Duran, is a thirty-six-year-old administrative assistant at Istanbul University. She is writing the story of her meeting with Maximilian Wagner, an elderly German professor, while on a flight to see him in Boston. They first met when she picked him up on his return to Istanbul, half a century after his initial post at Istanbul University.

On the surface, Wagner had come to make a speech reflecting on his years in Turkey when, from the years 1939 to 1942, he participated in Atatürk’s education reforms, modernizing the old Ottoman school, Darülfünun, into Istanbul University. But his motives were not in the interest of Turkish modernity. In Nazi Germany, he married a Jewish woman, Nadia.

After dropping him off at Istanbul’s Pera Palace Hotel, Wagner asks Duran if he can be picked up at 4 a.m. the next morning, to drive to the northwestern extremity of Istanbul, along the Black Sea coast. Against powerful bursts of wind, Wagner plays his violin and faints into the snow. Duran keeps him alive in a small hut, lying under a blanket with him.

Their platonic intimacy becomes a scandal. In the process, Duran is researching details of Wagner’s life with the help of her internet-savvy son. She confronts her brother and learns of their Armenian and Crimean ancestries. Wagner lost his wife in the 1942 Struma disaster, but as Livaneli shows, the degree of empathy for others is proportional to self-awareness.

Matt A. Hanson

Istanbul, Turkey