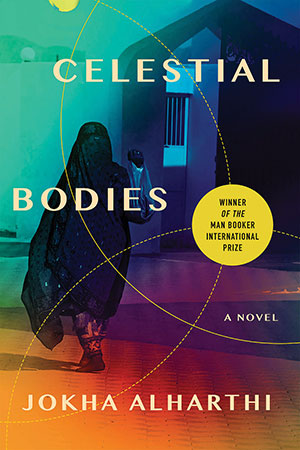

Celestial Bodies by Jokha Alharthi

New York. Catapult. 2019. 243 pages.

New York. Catapult. 2019. 243 pages.

THE WINNER OF last year’s Man Booker International Prize, Celestial Bodies narrates its stories through three generations of a family living against the backcloth of a pace of social change that is surely unprecedented in human history, in a country where traditional modes of life familiar to Abraham still coexist with the ultramodern: the grandchild of a former slave owner who dies in a modern hospital communicates by cell phone in a now-modern capital, while rural folk have upturned a recently acquired satellite dish to make a trough for livestock to feed from. Anyone seeking an introduction to the social and political history of Oman over the last century or so could do worse than read Alharthi’s novel, which features Zarifa, the former slave and concubine who, unlike her rebellious son, is still emotionally in thrall (Oman abolished slavery as recently as 1970), and, more centrally, the four middle-class women whose marriages, one aborted, embody different experiences of changing relations between the sexes.

Mayya accepts marriage to a man she does not know whose financial background is acceptable to her dominant mother, as, in a different way, does her younger sister, Asma, who will eventually become absorbed by maternity; Khawla latterly reacts against the early selfishness of a now-reformed and devoted husband and father and rejects him. London, Mayya’s daughter, is able to separate herself, at the cost of much pain, from an unworthy man met at the institution of higher education her bookish aunt Asma never dreamed of. The lives and travails of women who, in even the quite-recent past, would have rejoiced and suffered in unnamed obscurity are portrayed with delicacy and respect but no hint of modish sanctimony or anger (incidentally, Alharthi herself, the first female Omani novelist to be translated into English, has a PhD from a British university). Nor is male suffering absent or slighted: the sensitive Abdallah, Mayya’s loving but unloved husband, never recovers from the memory of punishment meted out to him by his brutal father.

The mode of narration by which the reader learns of these interlocking relationships is skillfully employed. Third-person omniscient narration focusing on one named character is interspersed with Abdallah’s first-person narrative. Close readerly attention is a sine qua non, but the alert reader will fit together the pieces of the jigsaw, eventually learning, for example, with the explosive effect a more straightforward narrative chronically arranged would have denied, what actually happened by the basil bush.

M. D. Allen

University of Wisconsin–Fox Valley