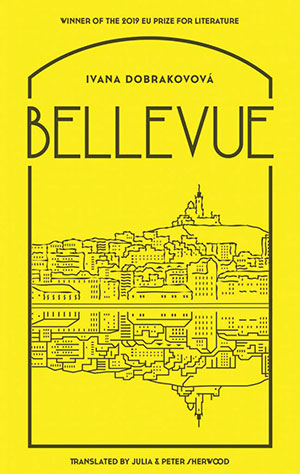

Bellevue by Ivana Dobrakovová

London. Jantar. 2019. 219 pages.

London. Jantar. 2019. 219 pages.

IN BELLEVUE, Ivana Dobrakovová, winner of the European Prize for Literature, pulls no punches for her readers or her protagonist, nineteen-year-old Slovak student Blanka, a volunteer at an international summer camp providing care for people with mental and physical disabilities. At the center in Marseille that gives the book its title, Blanka experiences disgust at the residents’ deformed limbs and uncontrolled bodily functions—as well as disgust at her own disgust. Faced with Laurence, a woman her own age with particularly severe disabilities, Blanka feels “awful, literally paralyzed by horror and helplessness,” when of course it is Laurence who is literally paralyzed. Blanka’s emotional distress shifts, however, to something much darker, as she progresses from depression to paranoid delusions to a full psychotic break.

Although the novel centers on Blanka’s mental illness, the passages describing the awkwardness and exhilaration of the semiflirtatious friendship between Blanka and Drago, a Slovenian volunteer, ring particularly true. As Blanka’s mental state declines, her narration deteriorates as well, with irregular punctuation, a blurring of inner monologue and outer dialogue, and pronoun slippage—all effectively conveyed by translators Julia and Peter Sherwood, who do well not to make things easy for the English-language reader in moving the text from Slovak. Nor do they seek to clarify Blanka’s delusional interpretation of events in relation to reality. While some of her fears, such as being sold to a harem, are clearly the work of paranoia, the various small cruelties she suffers from the other volunteers, who cannot manage her mental health, seem all too genuine.

Page after page, Bellevue supplies a relentless, even tedious, account of Blanka’s delusional thoughts. The reader’s fatigue only plays into the novel’s commentary on the limits and failures of empathy, however, which we see in Blanka’s inability to properly care for the residents and the other volunteers’ exasperation with her erratic behavior. One Swedish volunteer is left spent and sweating after pounding helplessly on the door of a public restroom Blanka has locked herself in. The novel shows us the uglier side of caregiving, when one gives in to frustration and exhaustion and thinks: Why can’t you just be well?

Corine Tachtiris

University of Massachusetts Amherst