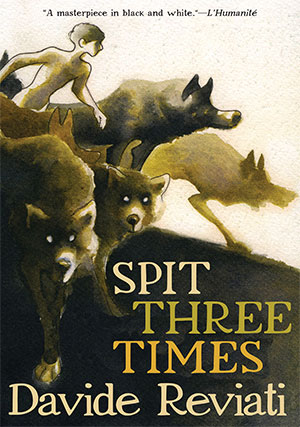

Spit Three Times by Davide Reviati

New York. Seven Stories Press. 2020. 568 pages.

New York. Seven Stories Press. 2020. 568 pages.

IT IS A RARE pleasure to find a graphic novel where energetic black-and-white drawings and simple but eloquent text are intertwined with such harmony, each enhancing the other. Of course, a driving narrative force is key here, and Davide Reviati’s Spit Three Times is a prime example of the melding of propulsive storytelling and a distinctive artist’s hand.

The narrative begins with a group of adolescent boys in rural Italy and follows them backward and forward in time. Guido and Grisu are at the center of the group, best friends from a young age but coming from very different circumstances, not socioeconomically, but because Grisu is of uncertain parentage and is something of a wild child. They smoke weed with their friends, play truant from school, and seem to be headed nowhere. And yet they develop a hardscrabble masculine morality, influenced by American culture and films. Iconic sketches of John Wayne and Alan Ladd show up in several panels, as do the names of Paul Newman and Al Pacino. American culture resonates with the boys, for they find few role models among the squabbling men of the village. Early on, the reader begins to piece together how these young men develop their sense of what it means to be a man while they engage in the timeless banter and athletic feats of youth.

Always in the background, and indeed often at the very thrumming heart of this tale, is the presence of the Roma. Young Loretta, near their age, often trails the boys, but they see her as an old crazy witch. Her family, the Stancis, had been interned in camps during the war, and Reviati offers us a page with a Roma arm revealing a number. The text is simple and wrenching, “Our numbers were preceded by a Z. It stood for ‘Zigeuner.’ Gypsy.” Over the course of several pages in the middle of the narrative, we get a brief history of Hitler’s attempt to purge the Roma, made ironic by the fact that their Indian and linguistic origins may make them pure Aryans. Yet they were demonized for miscegenation and were one of the two groups, along with the Jews, persecuted for racial reasons. As Reviati writes, “There wasn’t a single region in Italy without at least one concentration camp.”

The narrative reveals historical moments without pedantry and raises questions of who writes history and how we receive it. Surreal and supernatural elements appear and may be confusing at times, but they imbue the work with dreamlike and metaphorical depths. Throughout, there are allusions to Roma and Italian culture, the church, superstition, and even quotes from the most famous Roma poet, about whom Reviati gives us a lovely coda in “The Story of Papuzsa,” a welcome thirty-five-page addendum.

The young men achieve manhood in various guises, some successful, some less so, and each has become a fully rounded character. Ultimately, Reviati delivers a penetrating view of the vicissitudes of developing into an adult in a world that is fraught with generations of mistrust, anger, and poverty and yet is suffused with the vibrant enchantment of being human.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York