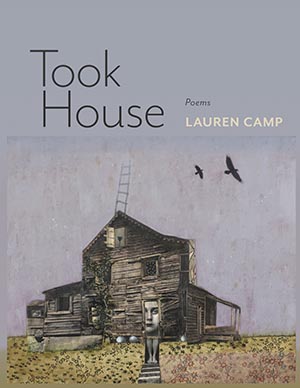

Took House by Lauren Camp

Took House

Tupelo Press

I will speak of this wind . . . of the seams of desire.

—Lauren Camp,

“Remember It Was”

The Greek mythological term omophagia refers to the eating of raw flesh in the context of Dionysian cult worship. It’s difficult not to think of the god of wine, fertility, and religious ecstasy when reading Took House, the fifth verse collection by Santa Fe poet Lauren Camp. The birds of prey—hawks, eagles, owls—that weave their way through (and onto the cover) of the book are synecdoches for the voracity and multiplicity of appetites that suffuse its pages—again, think of Dionysus being dismembered by the Titans. As Camp mentioned in a recent interview, “the predator-prey relationship” haunts many of these poems about human intimacy, in which the speaker might be hunter one moment, hunted the next.

The mind at play in Took House is also a raptor of sorts, alternating between alert observation and swift plunges into the depths of nature, art, embodiment, and memory. From Sappho to Rumi to Tracy K. Smith, poets have been writing about sex—and sex as a metaphor for poetry—since time immemorial. Here, the “sinew and lava” of both desire and loss pulse right beneath the surface of the poems, a “sublingual darkness” on and under the ravenous tongue. The same tongue transmutes flesh into song.

Poems about art, one of Camp’s longtime themes, also abound in Took House (see WLT, March 2011, Nov. 2015). “Because of all the jazz I’ve immersed [myself] in,” she notes in the same recent interview, “I’m used to hearing improvised and complicated rhythms. I like a little friction in my poems (and artwork).” Beyond art as theme, a Mingus-like stop-time rhythm punctuates several of the poems, as do visual breaks like the multiple ☐ in the poem inspired by Donald Judd’s aluminum box installation in Marfa, Texas (“Empirical Theories of a Box-Maker”) and the intralineal spaces in the poem about Piet Mondrian’s Composition No. II, 1920 (“Inward, Downward”). Here, the eye lingers in the blanks, while the ear learns to attune itself to the interstices and interplay between sound and echo.

“Bounty, bounty, bounty,” we read at the end of “Sharp-shinned Hawk.” Taken as bounty, the songbirds’ echo yet remains. Flesh transmuted into song.

Daniel Simon

Editor in Chief