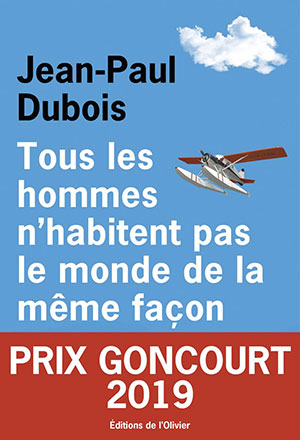

Tous les hommes n’habitent pas le monde de la même façon by Jean-Paul Dubois

Paris. Éditions de l’Olivier. 2019. 256 pages.

Paris. Éditions de l’Olivier. 2019. 256 pages.

A POSSIBLE TRANSLATION for the title might be: “There are different ways to inhabit the world.” Born in 1950 in Toulouse, where he still lives, Jean-Paul Dubois has been one of France’s more notable novelists since the 1980s. While he has a journalistic background, he is a relatively discreet, media-shy writer who tends to stay away from the Parisian literary establishment. His latest novel belatedly won the Prix Goncourt, the most prestigious French literary award. There are several idiosyncratic continuities in Dubois’s fictional work: the main protagonist of each of his novels was born in Toulouse; his first name is usually Paul; he tends to be an obscure, powerless character in a world that rewards only ruthless winners; his conjugal life is generally less than satisfactory; he is frequently busy gardening or mowing the lawn; he exhibits a fascination for automobiles and/or rugby; boating or plane accidents often play an important role in the development of the plot; pathos is regularly alleviated by dark humor; atheism, or the loss of religious faith, is a recurrent thematic element; a dentist, typically associated with pain, is habitually present in the narrative. Unlike the better-known French novelist Michel Houellebecq, whose characters inevitably wallow in self-hatred and pity, Dubois is a realistic, not nihilistic, writer who creates complex characters capable of evolving over time, of showing empathy for others, of finding moments of joy and beauty in world that is not entirely drab and hopeless.

In Tous les hommes n’habitent pas le monde de la même façon, the son of a Danish pastor and a French film theater manager (in Toulouse, naturally) winds up living in Québec as the manager and general mechanic (homme à tout faire or handyman) of a large apartment complex. He tidies up the hallways, services the heating system, keeps the pool clean (even though he is contractually barred from swimming in it), and of course mows the lawn. Over time, he becomes the helper or assistant of many of the aging, increasingly isolated residents of the complex. He also manages to build a lasting relationship with a woman who pilots small planes for a living. An airplane crash and an ill-intentioned boss will lead to a broader downward spiral in Paul’s life, and to an uncharacteristic outburst of violence on his part. Most of the narrative is told as a flashback, from the jail cell in Montréal that Paul shares with a French-speaking Hell’s Angel. As always in Dubois’s novels, the details of the plot are less interesting than the atmosphere and worldview conveyed by a somewhat bemused, certainly saddened, and perhaps wiser narrator.

The Goncourt is awarded for what is theoretically the best novel published in France each year. A highly subjective standard, to be sure. That said, Dubois’s novel will disappoint few readers.

Edward Ousselin

Western Washington University