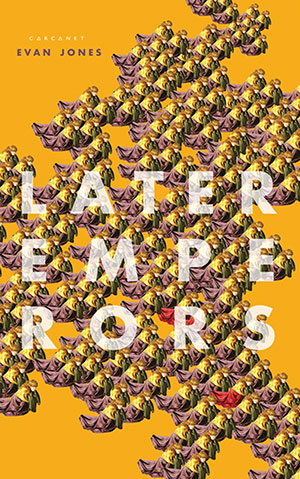

Later Emperors by Evan Jones

Manchester, UK. Carcanet. 2020. 73 pages.

Manchester, UK. Carcanet. 2020. 73 pages.

IN LATER EMPERORS, Evan Jones’s learning is clearly displayed in his engagement with Roman history and in the breadth of his allusions, but it is more deeply and subtly manifested in his deft exploration of such classical topoi as the ruins of time and the vanity of human desire. Jones’s spare, evocative, and imagistic verse offers, through half-glimpsed narratives of ambition and loss, a rumination on the transience of things in this world.

The book is divided into four distinct yet thematically related sections. The first part of the book covers some of the later western emperors from “the year of the six emperors” in 238 to the reign of Diocletian. Typical among them is the fate of Aemilian as Jones tells it in “Aemilianus the Moor”: “He stepped out of his tent one night / woken by what he thought were goats / and his soldiers sacrificed him.” This part of the book especially brings to mind such Renaissance works as The Mirror for Magistrates and The Ruins of Time as well as the broad tradition of memento mori.

The next two sections of the book turn to the Eastern Empire, giving voice to the Byzantine scholar Michael Psellos and to Anna Komnene, a Byzantine princess, scholar, and physician who was exiled for her failed attempt to usurp the throne. In the voices of these figures, Jones explores the relationship between political power and the life of the mind, evoking the classical debate of the active versus the contemplative life. Yet he also acknowledges that scholar and emperor share a common fate. “All glories to dust, yes, like / the library at Alexandria, / the Serapeum,” the scholar muses in “After Something Else.” Jones offers these meditations in delicate verse and in glimpses and fragments of these fascinating lives.

The final section of the book reflects more directly on personal loss through a longer poem, which is an imagined first draft of Plutarch’s Consolatio ad Uxorem, the famed ancient historian’s response to news of his small daughter’s death. The elegiac tone of this section makes it a fitting and poignant finale for the book, as Jones imagines Plutarch writing to his wife: “Life is made thin / and there is so much in the grave past / and graver future.”

Later Emperors is a lyrical book, somber yet lovely. Rare among works of poetry today, it offers not only beauty but also a wisdom rooted in time and timelessness.

Benjamin Myers

Oklahoma Baptist University