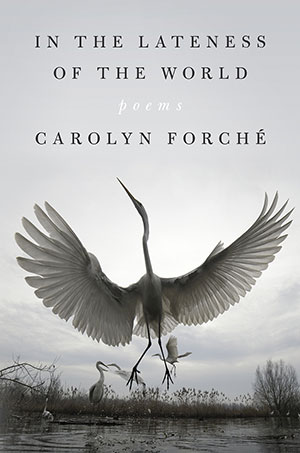

In the Lateness of the World by Carolyn Forché

New York. Penguin. 2020. 77 pages.

New York. Penguin. 2020. 77 pages.

DURING A 2019 INTERVIEW with Helena de Groot about the publication of What You Have Heard Is True, Carolyn Forché responded to a question about the act of noticing. After noting that this is a practice common among poets, she off-handedly put forth the only definition of poetry I’ve yet to hear that is large enough to hold the whole, ever-expanding world of it: “And poetry is a form of attention.”

And poetry is a form of attention; a definition that calls the thing by what we know of it and what we don’t—its relationship to other forms of attention, key, blurring the lines of art and life so that the thing which matters most is not the thing but attention itself.

Thanks to In the Lateness of the World—Forché’s first book of poetry in seventeen years—there are certain things to which I now pay more attention: that stones carry the memories of many destructions; that glass is the incendiary transformation of many small stones; that clouds, formed of the same substance that wears rocks to sand, are themselves an unending promise of resurrection. Each element—stone, glass, cloud—is part of a shared palette among the near-colorless poems. Together, they form a life cycle within the work that binds every living and nonliving thing; as if what Forché is always noticing are silent transmissions between human and stone, bird and cloud, each only brought forth through the poet’s use of language. “So that is how we ascend! / In the clawed feet of fallen angels / to be assembled again / in the workrooms of clouds.”

Anyone familiar with Forché’s work knows that her poetry of witness moves well beyond stunning imagery, having broad implications for the lives it hopes to remember and the readers it hopes to implore. The fallen angels from above are in fact zopilotes (buzzards), come to scavenge the remains of those killed by death squads in late 1970s El Salvador, many of which Forché searched for herself. The poem won’t allow her to leave out the depth of the horrors we are capable of, nor does it allow the reader to walk away in complacency. “You will be asked who you are. / Eventually, we are all asked who we are. // All who come / All who come into the world / All who come into the world are sent. / Open your curtain of spirit.”

Spirits hum through the book, with many of the poems acting as testament to singular lives taken by war, famine, greed, disaster. The pages are filled with imaginative language, but as one delves deeper into each poem, it becomes clear that the most striking lines are often just so because they exist simultaneously as impossible and true—not imagined at all but actualities that take on layered meaning in the context of the broader work and Forché’s activism: “After the earthquake, people moved into the family tombs. / Many graves now have light and running water.” These lines invoke the dogged determination to live amid immeasurable horrors and our uncanny ability to deny the inevitable, no matter how closely it is built around us.

There is in these poems a sense of responsibility: to the fullness of lives unnecessarily unbound; to poetry and its insistence on meaning; to attention and action, no matter the cost. And yet the work is open. It is filled with entry points, porous, allowing room for readers to make their way in, to touch the cold gray walls and leave with a newfound urgency for one another; for what they cannot see or hear, except in that shared “stone of the mind within us / carried from one silence to another.” (Editorial note: Read Forché’s remarkable interview with Chard deNiord from the January 2017 issue of WLT.)

Bailey Hoffner

University of Oklahoma