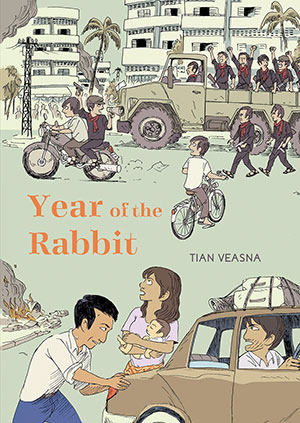

Year of the Rabbit by Tian Veasna

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2020. 368 pages.

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2020. 368 pages.

THIS GRAPHIC NARRATIVE begins in the uncertain days after the Khmer Rouge takeover of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Author and artist Tian Veasna, born just three days into the brutal regime of Democratic Kampuchea (1975–79), meticulously documents the daily lives of his parents and extended family during this period. Fine-lined pen-and-ink drawings are colored in pastels, with the occasional startling red—as in crosshatching of the symbolic Khmer Rouge uniform scarf. The narrative’s deliberate pacing is punctuated by full-page maps and survival “guides”: “To Avoid Trouble . . . Avoid carrying the following,” “A Day in the Life of the New People,” “Market value under the Khmer Rouge.”

A small child at the time, Veasna learned the details of how his own family experienced the Khmer Rouge regime only later, through interviews with his surviving relatives. The intimate images of everyday life coupled with spare, concrete dialogue anchors these people to the center of their own stories. Despite a steady beat, mostly unseen or off in the distance, of cries, gunshots, explosions, and mass graves, a remarkably quiet story unfolds—about the small ways people managed not only to meet basic needs but also to maintain personal connections under conditions of forced relocation and despair. If Veasna makes clear that trust is no guarantee of survival or happiness, he also shows that without trust—of those we know well and those we do not—we are lost.

This graphic narrative neither illuminates geopolitics nor simply reinforces what the world already knows: that the Khmer Rouge perpetuated violence in the name of “anti-imperialism” at a scale largely unimaginable. Politics comes up only occasionally, to explain the larger context and how so many Cambodians initially hoped the regime might create a better society after years of foreign-sponsored tyranny and colonialism. If I was left wanting more, it was for some follow-up, to shed light on this complexity; on how a fight against tyranny turns so very tyrannical itself. The book, instead, details a different kind of complexity, one perhaps just as powerful for its immediate practicality. In the end, this is a story of how people keep figuring out how to live on—after.

The determination in this book to avoid gratuitous violence and to instead focus on the minute ways people did—and did not—live each day is both admirable and effective in redirecting our gaze from horror to humanity.

Alison Mandaville

California State University, Fresno