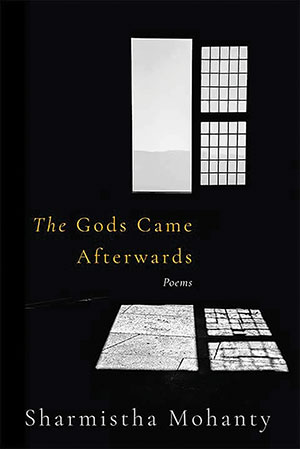

The Gods Came Afterwards by Sharmistha Mohanty

New Delhi. Speaking Tiger Books. 2019. 88 pages.

New Delhi. Speaking Tiger Books. 2019. 88 pages.

CLASSICAL INDIAN LITERATURE (religious as well as secular, in Sanskrit but also Prakrit, Pali, and Tamil) continues to inspire contemporary writers and to generate both new and innovative translations and original works of art. Bhakti poetry and the two major Sanskrit epics, the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyana, have been cast and recast in various creative forms and genres, with more or less explicit literary, cultural, or political agendas.

Sharmistha Mohanty’s long-awaited first collection of verse, The Gods Came Afterwards (see WLT, Winter 2019, 19), draws inspiration from the older substratum of the Rig Veda, a collection of hymns dating “from approximately 1200–900 bce.” As Mohanty explains in her notes: “At the time when the Rig Vedic hymns were composed there was a belief that new hymns must continually be made for use in rituals and worship. And in fact, the hymns were composed over hundreds of years by various poets and seers and passed down orally. It was only much later that these became the canon and nothing new was added. Around 1200 ce the hymns were collated, written down and composed into a text.”

This canonical process produced “the oldest religious and spiritual text still in use,” but in so doing extinguished the creative source that had made it possible. Reading or chanting these hymns ritually or ceremonially is not the same as composing them, memorizing them, and transmitting them orally “over hundreds of years.” Mohanty shows us (and this is perhaps the single most extraordinary achievement of this book) how natural and spontaneous a prayer, a supplication, or a hymn can be, and how necessary to a better understanding of our condition “in this place where we become.” Such a deeper understanding can only be human, rather than divine or theological.

In Mohanty’s rarefied vision, it implies an ongoing endeavor to attain broadness out of narrowness, to envision the infinite and the universal in humanity’s all-too-finite and restrained experience (“We see nothing / behind nothing ahead / These worlds are broad above / beyond our knowing”). Narrowness equals darkness and blindness, the ignorance that is a consequence of unknowing; therefore the invoked path is toward light, comprehension, and the gift of seeing (“Unclose / the nights / unbind / our thoughts / give us an / uncircumscribed / earth / make us of / broad gaze”).

Mohanty’s elevated diction runs the gamut from incantatory (“breath by breath / saying saying / syllable by syllable / making, meaning”) to aphoristic (“Who comes through / fire shines in / ashes”) and, in true Vedic style, tends toward the self-referential (“Bearing light in / the mouth / I light a syllable / and all the other / syllables follow . . . / . . . With my labour / I illuminate / ancient things / bearing light / in the mouth / at night’s / boundary”). Lastly, it has all the piercing or electrifying intensity of the best minimalist poetry, urging the Reading Eye to take off and rise above the field of writing, to morph into a Singing Voice, and to soar unfettered by the laws of either typography or syntax.

Graziano Krätli

New Haven, Connecticut