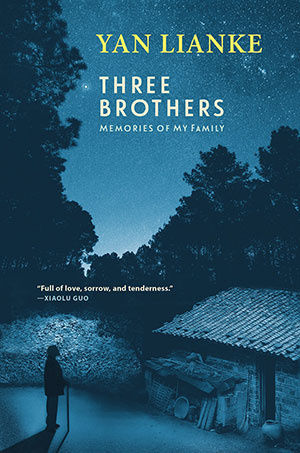

Three Brothers: Memories of My Family by Yan Lianke

New York. Grove Press. 2020. 209 pages.

New York. Grove Press. 2020. 209 pages.

YAN LIANKE'S Three Brothers: Memories of My Family is a powerful portrait of the trials of daily life in Song County, Henan Province, in the 1960s and 1970s. The memoir not only provides a deeply heartfelt account of his big family—including his father, his uncles, and his cousins—but also offers a philosophical meditation on dignity, duty, death, and the bond of a rural Chinese family.

Yan’s father set his mind on fashioning the tile-roofed house that would serve as Yan’s brothers’ bridal “mansions.” Thus, he overworked day and night in spite of his declining health, which resulted in his early death at the age of fifty-eight. In order to break away from country life, Yan’s first uncle sent his most-loved son into the army, but he was abused by the commander and hanged himself in consequence. Yan’s first uncle was heartbroken, indulging himself in gambling to waste his remaining life. Yan’s fourth uncle, who was fortunate to have escaped the harshness of rural life by working in a cement factory, became a “bowed-head”—half-urban and half-rural—and was looked down upon by city people. After retirement, he came back to his hometown, only to find that he was isolated from country people.

The memoir is the chronicle of a family as well as a record of history—in case the younger generations tend to forget. It does not mean to “bash the government”; however, it did skate over historical events such as the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, and the Three-year Natural Disaster, during which period millions of people starved to death (“the revolution does not produce grain, only political fervor”). The social injustice and inequality between city and country is touched upon throughout the chapters of the book, and the most appalling injustice occurs when, during the movement of sending “urban youth” to the countryside, a villager attempted to rape a young woman from the city and was sentenced to death immediately, whereas when an urban youth raped a village girl, he could escape without any punishment, except for some “monetary compensation.”

Besides, the memoir is also a literary testament to the greatness of humanity. “Goodness was the foundation and the basis of our humanity,” as Yan declares. It depicts the sense of duty of three brothers, who shoulder their responsibilities from the moment they become “fathers.” It displays the sense of dignity, which is “the spirit of life”—Yan was once beaten severely by his father for stealing and telling lies. It describes the bond and warmth of the family: Yan’s elder sister sacrificed her own opportunity so that Yan could enroll in high school. In this sense, the book is a celebration of the power of one family to hold together in spite of harsh circumstances.

Even though all three brothers are illiterate, they have deep insight toward life and death, like philosophers. According to Yan, “Human life is that finite distance between you and death, and if you progress at a certain pace, it will take you a considerably longer period of time to reach death,” which is the essence of traditional Chinese wisdom.

Perhaps this is the reason why “I had to return again to that land . . . since regardless of where you go, and regardless of how far you travel, your home and your land will always be under your feet,” as Yan declared in his prefatory essay, “The Home from Which I Walked Away.” In times of darkness, Yan can always find the gleaming light of humanity by returning to his roots.

Yang Jing

Nanjing Normal University