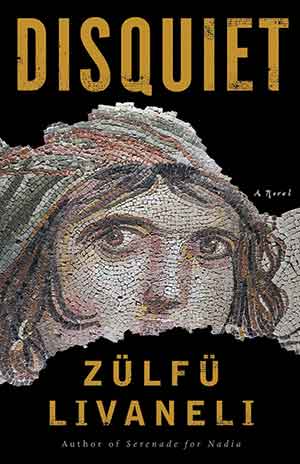

Disquiet by Zülfü Livaneli

New York. Other Press. 2021. 176 pages.

New York. Other Press. 2021. 176 pages.

A SINGER, NOVELIST, and activist of progressive, secular renown, Zülfü Livaneli returns to anglophone readers with a slim narrative, polished into English from Turkish by translator Brendan Freely. Disquiet is an ambitious effort to tease out the unshakable geopolitical quandary into which too many are born, between the internal conflicts of the East and violent xenophobia in the West, all in under two hundred pages.

The ghost of Hussein haunts his schoolmate Ibrahim, a journalist who has made a career in Istanbul and has taken time away from a messy divorce to return to Mardin, the city that raised him. Livaneli has the eyes of a hawk, as he swoops down over the landscape of his country with a touristic bent, utterly objectifying its people in the style of an orientalist romance.

The thickness of the mahleb-flavored Assyrian wine goes down slow, but easy, in the throat of the narrator, who speaks of his “desert gazelle,” a Syrian Yezidi refugee named Meleknaz, whose description would evoke the Western world’s sympathy like that of the famed Afghan Girl by photojournalist Steve McCurry. Disquiet very much trains its often overwhelming male gaze on her Yezidi culture, which Livaneli spell-checks frequently as Ezidi.

As if it were not enough that Meleknaz is subject to genocide, war, exile, raising a blind child, and moving out of a refugee camp in Mardin to find work while recovering as a rape victim, she is also doggedly pursued by two Turkish men. First, the late Hussein, a star Quran student when he shared school uniforms with his childhood friend Ibrahim. Out of the goodness of his heart, he would help refugees encamped in and around his ancient city.

The sight of Meleknaz, a twenty-first-century Middle Eastern damsel in distress, inspires him to write love poems, in the classical tradition of Islamic mysticism that cultivated the likes of Rumi. Yet his star is crossed by pressure at home to steer clear of the Yezidi girl who, in his mother’s opinion, worships the devil. His domestic problems are only the beginning of his unrequited love as an ISIS militant interprets their flirting as an offense to Islam to violent effect. Though Hussein survives and later immigrates to Germany, tragedy strikes him when he is caught in the hateful sights of neo-Nazis and stabbed to death in the streets of Duisburg.

Livaneli might deserve praise as a Turkish author who has given agency to the Yezidi struggle for survival as victims of genocide, by characterizing their beliefs, customs, and history at the heart of his late-career novel. The videoed decapitations, mass migration, slave markets, and gang rapes that fester in Disquiet remain as a deep, permanent scar on the international community. Yezidi people, as one of many stateless minorities in the Middle East, include Christians, Kurds, and many others. Their subjection to the shuffle of sacrifice zones in the ongoing debacle of capitalist globalization is all but silenced.

In the guise of a quasiromantic foray, led by a knockabout journalist, Livaneli has only reflected the chasm of difference between him and the helplessly dehumanized, impersonal portraits he has sought to vivify through his heavy-handed, objectifying storytelling. By concluding with Meleknaz poised to speak her truth for a journalist, the metaphor is clear.

Ultimately, however, as a passing piece of airport fiction it might tease a traveler’s curiosity on a layover to Mardin. The light book, for its blunt faults, has the potential to broaden the context of listening, informed and empathetic, to the plight of those who, on all sides of the geopolitical spectrum, await their chance to speak. The translation of Livaneli into English, and Disquiet in particular, might sound like glorified mansplaining, but its point is urgent.

Matt A. Hanson

Istanbul, Turkey