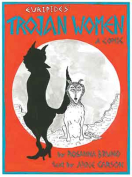

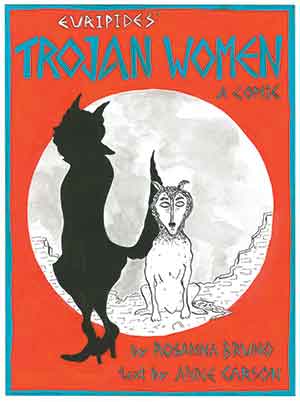

Euripides’ Trojan Women: A Comic by Rosanna Bruno & Anne Carson

New York. New Directions. 2021. 96 pages.

New York. New Directions. 2021. 96 pages.

TO CLASSIFY ANNE CARSON’S version of Euripides’ play The Trojan Women as a translation is to use the term lightly, for, in collaboration with Rosanna Bruno, she has transformed it into a graphic novel, fiercely experimental in both word and image. As she previously demonstrated in her rendering of Sappho’s poems, If Not Winter, Carson is an exceptionally gifted translator, but here she has deliberately cast aside literal translation. By abandoning Euripides’ original words and syntax, and indeed the task of literary translation itself, Carson lays bare the central emotion of the women in the play and forces us to feel in our very nerve endings what it is like to be abandoned.

Carson teams up with Bruno to produce a playfully surrealistic portrayal of the Trojan women as they have never been seen before—as scraggly dogs, woebegone cows, a scrawny split tree limb, or an oddly abstracted pair of overalls tethered to an owl mask. Yet there is brilliance in Carson’s seemingly improbable conception of the play as a comic book—the daring change of format has the effect of heightening and revitalizing the primary drama of women objectified and enslaved. In Greek myths, the emotional pitch of the characters is so strong that their very bodies can no longer remain intact but erupt into the changed forms of spider, bird, and tree. Similarly, in Carson’s latest work the intense level of female mourning has reached such extreme intensity after the Trojan defeat that the sufferers can no longer be constrained by their human forms—the very force of what they feel turns them into objects of flora, fauna, weaponry, and mask.

As in Carson’s most recent work, Norma Jeane Baker of Troy (WLT, Summer 2020, 82), the setting assumes knowledge, here that after years of war fought over the kidnapping of Helen of Troy, the Trojans were tricked by the Greeks into opening their city gates to let in a Trojan horse that allows the Greeks to enter and destroy the city, thus winning the war. The spokesperson, portrayed as a mangy-looking dog, is Hekabe, previously queen of Troy, whose devastating losses include virtually all her children and her husband, Priam. Directly addressing the audience in brutally blunt, scalding words, she narrates what has happened to the Trojan women and predicts their enslavement and death, embodying as she speaks the forbearance their fate decrees: “We can’t go on. We go on.”

The language that Carson uses is purposefully bold—she slyly mixes the stylized formal conventions of Greek drama, such as the poetic lyricism of choral odes, with the casually modern colloquialisms of her main characters’ soliloquies, a combination that startles but creates arresting effects. In an introductory dialogue, the god Poseidon describes Troy as “crouched on the plain like James Baldwin with eyelids drifting down and drifting up,” and the goddess Athena replies that although the Trojans were once her enemies, “now I want to cheek them up and give the Greeks a bad voyage home.” Carson manages to make her eclectic blend of verbal elements work, the catastrophic extremes of the story made more buoyant and easier to absorb by the coolly chosen words and the humorous comic-book tone.

Carson’s aim in recent works is clearly to unsettle her audience—she offers straight talk one minute and madcap play the next. In The Trojan Women, her remarkably synthesizing imagination brings traditional Greek drama and the contemporary comic book into strange and wonderful balance.

Rita Signorelli-Pappas

Princeton, New Jersey