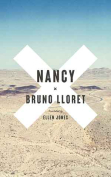

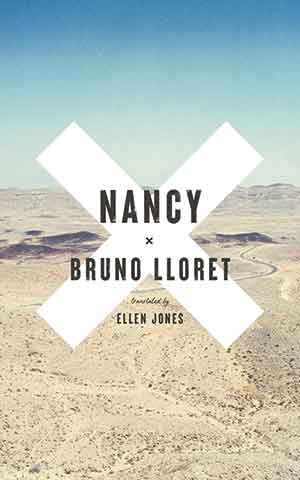

Nancy by Bruno Lloret

San Francisco. Two Lines Press. 2021. 156 pages.

San Francisco. Two Lines Press. 2021. 156 pages.

FIGHTING A DREADFUL illness, the eponymous narrator of this sobering novel reflects on a life shaped by personal misfortune and broader social ills. Nancy Cortes has lost a mother, a brother, a husband. She’s about to lose much more. Nevertheless, her devout father says she needn’t get too glum. After all, they’ll both be dead soon enough. “This world is a desert of crosses,” he says. Considering what she’s endured, this qualifies as a pep talk.

Bruno Lloret’s Nancy is a powerful English-language debut about a woman who summons the fortitude to persist amid acute suffering. Set primarily in Chile, where the London-based author was born, the novel takes the form of a harrowing memoir with a distinctive typographical feature: Lloret peppers his book with X’s. Sometimes, two X’s take the place of punctuation marks. Elsewhere, they appear by the dozens, separating paragraphs and annexing large chunks of several pages. Lloret has said that the X’s suggest “silences, white noise, gaps, breathing.” They evoke the incisions and X-rays of Nancy’s medical treatment; when they appear in abundance, they resemble rows of Christian burial plots—“a desert of crosses.” This is apt symbolism for a sorrowful tale.

The novel opens with Nancy in the back of a truck, apparently being smuggled across a stretch of South America. The story eventually circles back in an understated, satisfying final chapter. In between, she shares episodes from a painful life, fortifying herself with irony and gallows humor. As a child, Nancy is her mother’s favorite target for verbal abuse—this is detailed in an expletive-laced footnote—and her brother’s traveling partner on trips to the seaside. The X’s dwindle during one such outing, suggesting a moment of tranquility; they return when he disappears without explanation. Meanwhile, as women’s murdered bodies are discovered on a nearby beach, a local man sexually preys upon Nancy. In time, her mother deserts her, and her father succumbs to religious charlatans.

Married as a teen to a man twice her age, Nancy watches her husband get drunk every night. When he dies in an accident at a tuna-packing plant, she wonders if she’ll be granted “a moment alone with the 2,500 cans containing my deceased husband.” When disease attacks her uterus, she calls herself “Nancy Cancer” as treatment leaves her “skeletal, mutilated, barren.” Lloret invokes Exodus, Revelation, and other books of the Bible, and Nancy herself calls to mind Job. She’s beset by adversity; she refuses to quit. A nuanced character study, this book is also an indictment of misogynists and their enablers.

Lloret occasionally relieves the tension with instances of fleeting beauty. In one, Nancy recalls the “collective intimacy” shared by bargoers listening to “a Peruvian waltz, or something even sadder.” Years later, she still favors downbeat songs. Some days, they’re her only solace.

Kevin Canfield

New York