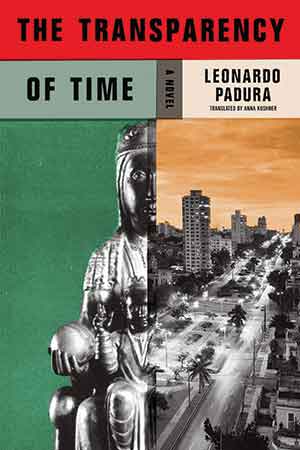

The Transparency of Time by Leonardo Padura

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2021. 402 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2021. 402 pages.

IN DISCUSSIONS OF writers considered to be pushing the limits of the traditional detective story, the works of Cuban writer Leonardo Padura are frequently cited, and his latest translated novel, The Transparency of Time (La transparencia del tiempo), demonstrates the ambitious directions in which he is attempting to stretch the conventions. The main character of the novel is private detective Mario Conde, a former policeman and the protagonist in Padura’s four novels internationally known as the “Havana Quartet.” Conde is feeling the effects of age, drinking too much (like any hardboiled detective worth his salt), all the while confronting the merciless consequences of government-quality rum, intimations of mortality, and a prostate growing like a potato. The investigation this time involves the search for a black wooden Madonna to which the owner attributes a miraculous cancer cure, a Madonna of mysterious provenance stolen by the owner’s gay lover.

Murder, of course, becomes part of the case as well as a transcendentally beautiful, part-Asian femme fatale, and a chase through the “lower depths”—a shantytown on the city outskirts mostly populated with illegal migrants from the eastern areas of the island desperate for work. Corruption in the art market becomes relevant to the question of why anyone would murder for this particular, seemingly insignificant religious artifact and provides the opportunity (as with Hammett’s Maltese falcon) to attract a number of oddball characters who would sell their mothers for an antique cigar box. So far, so good.

These tropes and attitudes that have kept tough guys wisecracking for nearly a hundred years will rest pleasantly in the bellies of private-eye fans. There are at least two things, however, that make Padura’s novels into something more than the usual stuff that dreams are made of. The first of these is the portrait of life in Havana. Padura is interesting as an internationally known figure in not having taken what must have been many opportunities to escape the economic and other strains of living there. He drops details from page to page like a 1950 Chevy dripping the dishwashing liquid that frequently substitutes for transmission fluid in the embargoed country. Conde, for example, in passing compares the cheap government rum to rum made in the one factory that still follows the old Bacardi recipe. And then there’s the previously mentioned migrations of eastern Cubans; the peculiar relationship between the expatriate Cubans in Miami and their counterparts still on the island; and the Kafkaesque motivations of policemen, some true believers in the revolution and some more cynical than a thrice-married used-car salesman.

The best detective novels, whether by Raymond Chandler or Henning Mankell, have long offered more about the societies that spawned them than casual readers digest (or possibly even care about), and Padura, by meticulous attention to detail and without preaching, is an expert in making the reader know what kind of life is possible in that bankrupt dictatorship. How do they get by? People make love. They share dinners and sit on the humid patio knocking down cocktails. They argue. They laugh. They know what the wrong thing to say is, and sometimes say it just to get away with it.

Padura’s ambitions in this novel, however, go toward more than just a faithful representation of the social conundrums of living in his country at present. Padura reaches for an epic vision that transcends the mundane, connecting the novel’s detective story and his nation with the history of Spain and the Knights Templar, similar to the way he expansively weaves the history of the Jews into Heretics, his lengthy book centered around the quest for a Rembrandt smuggled onto the ill-fated 1939 ship SS St. Louis with its homeless refugees. The artworks in the two novels are more than MacGuffins for Conde to seek. The unusual blackness of the Madonna suggests the complexities of race in Cuba, for instance, without Padura tub-thumping on the issues, in much the same way that the economic problems of Cuba are always present but generally accepted as the backdrop. The full story of the Madonna is never revealed to Conde and appears in chapters set in the fourteenth century that some reviewers have criticized as being irrelevant to or too disconnected from the mystery. If you want to read another routine private-eye novel, have at it, but demanding a novel conform to your taste rather than trying to grasp what the author is saying is a backward way of reading.

Personally, I found the historical sections more interesting than the detective story, perhaps because I am more familiar—perhaps too familiar—with the genre. Nonetheless, each part enlarges the other, more than just by addition, in yet another rich novel by Cuba’s master novelist.

J. Madison Davis

Palmyra, Virginia