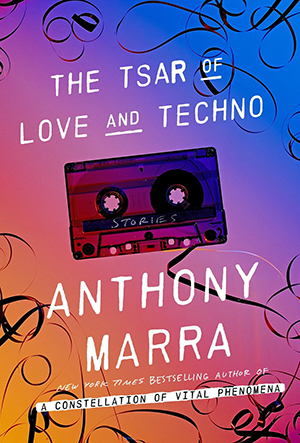

The Tsar of Love and Techno by Anthony Marra

New York. Hogarth. 2015. 332 pages.

New York. Hogarth. 2015. 332 pages.

After the signal achievement of Anthony Marra’s first novel, A Constellation of Vital Phenomena (2013), one returns with pleasure to Chechnya and Russia for more memorable characters, conflicts, and absurdity. This time, from the Russian perspective, there is less fatality in the air than individual deaths and disappearances, understood well enough so that those who adapt quickly might survive. If one is clever, one can even maintain certain constancies behind a chameleon exterior.

One functionary has “ascended to the rank of commissar by welcoming the lunacy the world so graciously handed him.” There is a deputy curator whose art museum has been destroyed, with its best paintings sent to Moscow, who keeps damaged paintings in his apartment. In his new position as tourist director, he restores Grozny, rated the most devastated in the world, by painting word-pictures of buildings that were once standing for Chinese tourists.

Or the former art student, now a leading censor of photographs, carefully airbrushing out disgraced persons from historic pictures, sometimes extending background, sometimes replacing the face with an unknown or anonymous person. His constancy consists in the face he repeatedly inserts, his brother at various ages, an unknown man who was executed, supposedly for being too religious.

Or there is the execution of a man in a forest of metal trees, with plastic leaves. One killer’s gun jams, and the man on the ground—a former executioner—tells him to look in the barrel so he can spot any obstruction more clearly and then pull the trigger several times. It’s a world Kafka could embrace.

The key locations are a meadow in Chechnya and Kirovsk, stories set between 1937 and 2013. The stories focus primarily on a group who grew up in the Siberian town, memories of a nickel-producing, heavily polluted landscape that somehow nurtured them well enough to live in and sometimes succeed in a country undergoing profound change.

The other unifying feature is a nineteenth-century painting of the same Chechen meadow, subsequently mined, a place haunted by the deaths of a wife and child sent there to avoid the ravages of urban warfare. The husband repairs a hole in the painting and places two shadowy figures there. The painting pops up in the living room of a former Miss Siberia, from Kirovsk, who gives it to a childhood friend, in memory of his brother who also died in that meadow. Thus, three stories become improbably, though naturally, related.

As characters loop into one another’s stories, some readers may be troubled. Others, fond of the characters, want their joining. Perhaps Anthony Marra is a failed postmodernist, afraid to acknowledge the futility of our striving; perhaps he is a skeptical humanist who knows our stories will inevitably reveal some common bond, even in the last words of an executioner to his victim. I stand undecided, but impressed and moved.

W. M. Hagen

Oklahoma Baptist University