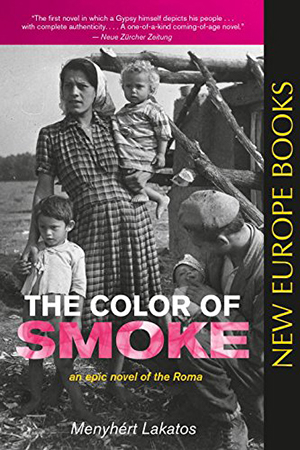

The Color of Smoke by Menyhért Lakatos

Williamstown, Massachusetts. New Europe Books. 2015. 480 pages.

Williamstown, Massachusetts. New Europe Books. 2015. 480 pages.

Menyhért Lakatos is acclaimed as Hungary’s foremost Romani author, and his novel Füstos képek, translated by Ann Major as The Color of Smoke is considered to be his magnum opus. It is semi-autobiographical, based loosely on his own experiences as a young man coming of age in Hungary ln the 1930s and early 1940s. Lakatos (1927–2007) is also the award-winning author of two novels, a novella, five collections of stories, and one volume of poetry. The Color of Smoke first appeared in its original Hungarian-language edition in 1975. It is a picaresque and somewhat salacious odyssey of a nameless protagonist, written in the first person, who grows up as a member of a marginalized minority group, living in a shantytown ironically called “Gypsy Paris.”

As a child, Lakatos’s protagonist is drawn to his grandmother; her stories are his link to a former and better nomadic existence in the now-defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire. She is the conduit from the vanished past of the Roma and their ever-worsening present as Hungary is drawn more and more into totalitarianism. His life suddenly changes when a near-tragic but fortuitous event enables him to attend high school until he is expelled, along with the Jewish students, after Hungary joins the fascist camp.

Lakatos skillfully weaves Romani customs, language, and even herbal remedies into the story as the novel’s characters interact with one another and with the greater non-Romani world. He also describes the constant hunger during the long, cold winters when the bigger dogs have to be killed to prevent them from eating the small children and the horses are butchered for food because there are no barns or fodder. In one instance, the Roma are even forced to eat pigs from the carrion pit after they died of swine flu in order to survive. Lice and vermin are rampant, and there are constant outbreaks of scabies, which the women treat with tobacco. But despite their suffering, Lakatos shows how the Roma manage to survive, a tribute to their ingenuity and fortitude.

When he is sixteen, the protagonist has a brief marriage in another settlement to a fourteen-year-old bride, whom he is then forced to abandon as he continues his odyssey with his friend, Bada, which include more brief romantic episodes with Romani girls. He also has one foredoomed crush on a blond Hungarian fellow student who is the daughter of a local aristocrat. She is far beyond his reach, but she capriciously manages to save his life when the Hungarian students drown the only other Romani student in the school outhouse.

The story ends when the Germans invade Hungary. Soldiers surround “Gypsy Paris” and prepare the inhabitants for transport. As the train pulls out of the station, we can only surmise where they are going, as the Nazi Holocaust finally engulfs Hungary’s Roma.

Ronald Lee

Hamilton, Ontario