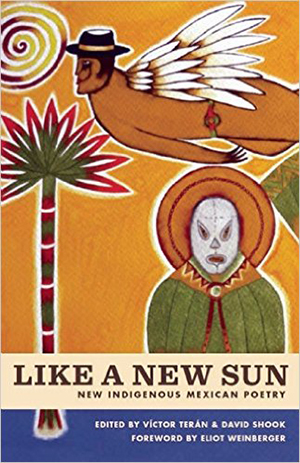

Like a New Sun: New Indigenous Mexican Poetry

Los Angeles. Phoneme. 2015. 240 pages.

Los Angeles. Phoneme. 2015. 240 pages.

While exiled in Madrid, the hypercosmopolitan poet Alfonso Reyes wrote Visión de Anáhuac, 1519 (1915), an exquisite narrative of Tenochtitlán and its conquest by the Spaniards. In 1957 Octavio Paz finished his masterpiece, Piedra de sol, a poem whose circular structure and hendecasyllables allude to the orbit of Quetzalcoatl (Venus). The philosopher Miguel León Portilla published Los antiguos mexicanos a través de sus crónicas y cantares in 1961, translations from indigenous poems popular to this day. Many Mexican poets, however, express ambivalence or disdain for contemporary poetry written in Zapotec, Nahuatl, etc. Separate festivals are held for poetry written in indigenous tongues. Fewer pages are meted out for Zapotec or Mazatec poets in major anthologies. The message is clear: the poetry that really matters in Mexico is that which is written in Spanish.

If just for that, the publication of Like a New Sun, edited by Víctor Terán and David Shook, is cause for celebration. Such translators as Jerome Rothenberg and Eliot Weinberger effortlessly transfer the exuberant imagery of poems by Terán, Cuevas Cob, and others into English. The Zoque poet Mikeas Sánchez demonstrates how the indigenous poetry of Mexico weaves the ancient with such contemporary imagery as “My memory is the black box of a plane without return / How did it reach the libation of sea water of such sweet saltpeter,” as rendered into English by Shook. All through the anthology, the poems emphasize that indigenous poetry in Mexico is not an outsider art but a vibrant gathering of voices.

Other poets such as Juan Hernández Ramírez, writing in Eastern Huasteca Nahuatl, echo the flower songs of the ancient Mexica, yet in the able translation of Coon and Shook, the “green moon” and “liquid flower,” the “dance with the wind,” brim over with a new light. Rothenberg offers translations from the Mazatec of Juan Gregorio Regino; his flowing cadence unleashes a similar energy as found in that other Mazatec poet whom Rothenberg translated: María Sabina. In “Cantares,” Hernández Ramírez chants: “Say whore. / Say mistress of fire. / Say macaw feathers. / Say fragrant flowers. / Say doors to the shy. / Say place of the images.”

The anthology opens with sobering words by Shook about how “some 90 percent of the world’s 7,000 languages,” the languages present in the book, are “threatened with displacement,” yet there is comfort in knowing that Isthmus Zapotec poetry thrives. In the tradition of Pancho Nácar and Macario Matus, Víctor Terán offers some of the best poems in the anthology. An international poet who has translated Wordsworth and Bukowski into Zapoteco, Terán’s sharp imagery is well conveyed in translation. Knowing that he is standing his ground, defying the pressure to write in the language of the colonizers, Terán asks: “Now bring me / the birds / that you find in the trees, / so I can tell them / if the devil’s eyelashes are curled.”

Anthony Seidman

Hollywood, California