The Young Literary Scene in Kosovo: A Conversation with Ragip Luta

Kosovo is a young and vibrant country striving to prevail in a harsh new Balkan reality. Ragip Luta is the director of Kosovo’s Festival of Literature in Orllan. The festival is held annually in July by Lake Batlava, bringing together Kosovar and international writers and artists. The festival’s theme for 2015 was “Writers and Writing in Exile.” It brought back to Kosovo exiled writers such as Xhevdet Bajraj (Mexico) and Skënder Sherifi (Belgium).

Peter Constantine: Kosovo’s international festival of literature in Orllan has over the last few years attracted a number of Kosovar writers and international literary figures. Do you see a new energy in the Kosovo literary scene?

Ragip Luta: Yes, there is definitely new energy on the Kosovo literary scene, no doubt about it! Although it is a small scene, it is colorful, vibrant, and exciting, with many more opportunities than there used to be for poets, writers, and playwrights to publish and interact directly with the public. I guess this new energy is natural in a young country with the youngest population in Europe—people experiencing for the first time the early years of liberation, freedom, and independence. If we take as our time frame the fifteen years since the Kosovo War, hopefully this could be something like the onset of the 1960s for the Kosovars, with all its creativeness. And all this, of course, compared to the situation before the Kosovo War.

PC: The Albanian writer Ismail Kadare has described historic Kosovo as a land of different languages and cultures. What is the scene in young literary Kosovo today?

RL: Writers in Kosovo continue to write in Albanian, Serbian, Turkish, Romani, and even Gorani, a South Slavic dialect. And the scene has been enriched following the war in 1999, with more Albanian writers in Kosovo resorting to Gheg, which is the dominant spoken dialect among Albanians in Kosovo and northern Albania. The Gheg variant of Albanian had been neglected for several decades following the adoption of Standard Albanian in Albania in 1972.

PC: From what I have heard, the dictator Enver Hoxha had actually made Gheg illegal in Albania, though it was the language of the great northern Albanian epics.

RL: Well, it was practically “outlawed” and reduced to “reactionary” status during Ho-xha’s regime. For example, Gheg was only used in movies in communist Albania “to typecast ‘bad guys,’ reactionaries, traitors,” according to Migjen Kelmendi, a Kosovar rock musician and author who was the first to publicly break the taboo of using Gheg in the media just before the 1999 war. He now runs the only TV channel in Gheg. Or to quote Primo Shllaku, a poet from the northern Albanian city of Shkodër, a frequent guest at our festival, “Gheg was banned the way free speech was banned.”

PC: You also mentioned that there are authors in Kosovo who write in other languages.

RL: There are Kosovar Serb writers who make use of the local Serb dialect, too, and then there are those who write in Turkish and in the Romani/Roma language. But these literary scenes in Kosovo are not unified, and you can hardly find Kosovar Albanian and Serb writers getting together, as would have happened occasionally before the 1990s. Small steps have recently been taken to foster some kind of cultural cooperation and exchange between Prishtina and Belgrade, but this can’t be said of the Albanian and Serb writers in Kosovo.

PC: Who would you say are the interesting writers in Kosovo today?

RL: Traditionally, Kosovo’s forte has been poetry. Personally, I like Ndriçim M. Ademaj, who—I can’t help mentioning—looks a little like a bearded Jim Morrison. In one of his poems he has said that his head is a “mental hospital”; in another poem he sees himself as a “ricocheting bullet wandering around the world,” unable to pierce his own head. Hardly any sunnier is the world of another of my favorite young poets, Shpëtim Selmani. Last year one of his poems was described as “a spectacular exercise in concise pessimism” in a competition organized by the UK’s Guardian newspaper and the German newsmagazine Die Zeit. He’s about thirty years old and describes himself as a positive pessimist! He says that poetry helps him be true to himself. Then there is Ervina Halili, whose somewhat surrealist imagery I find quite refreshing. And also Imer Topanica, who like Ervina writes mostly in the Gheg dialect, and who brings mysticism and spirituality to his work. No wonder he likes to quote among his influences Tranströmer, Kahlil Gibran, Omar Khayyám, and Rumi. It is a generation of brave young poets with a bold new language bringing new themes and new ways of seeing the world around them.

Whereas earlier generations of writers—understandably, because of the circumstances and censorship in the former Yugoslavia—were more hermetic, and you had to struggle to understand their hidden messages, these young writers are saying it plainly now, whether they write about love, war, or everyday life, and do not hesitate to express their pessimism, disillusionment, and even despair at how some things have turned out in the new and, for the first time, independent country. There are also some playwrights who are creating a buzz in theater circles, and not just in Kosovo, but I would say that—and this is not just my opinion—we’re still waiting for some novelist to burst onto the scene.

PC: In neighboring Greece a first generation of young poets is reacting to the dramatic upheavals of the dire crisis that country is facing. Is the “positive pessimism” of poets like Shpëtim Selmani an indication of optimism?

RL: I am not so sure about that. It’s been fifteen years since the Kosovo War, and it is true that the freedom people have been enjoying these past few years is without precedent in Kosovo’s history. But the economic situation is extremely difficult, with the youth unemployment rate higher than it is in Greece, and the poverty rate the highest in the region. People are continuing to see asylum in European Union countries as a way out of that predicament. I was reading the other day that Kosovars are, along with Syrians and Afghans, among the top three nationalities seeking asylum in Austria so far this year. Many Kosovars feel that they are being ghettoized as the only nationality in the western Balkans who need visas in order to travel to European Union countries. And yet there is so much energy in Kosovo, as young people make up the largest percentage of the population: 53 percent of our population is under twenty-five years of age. We have the youngest population in Europe. Depending on how things develop, things could go either way: at the beginning of the year we had some of the worst unrest since the Kosovo War.

PC: How are Kosovar writers faring in this crisis?

RL: I don’t think there is a single writer in Kosovo at the moment who can earn a living from the books they publish. They all have to have other jobs as well. We are a small country with a small writers’ market, and it still hasn’t been possible for our authors to break into the market in Albania, despite our having the same language, whereas authors from Albania are very much present in Kosovo. It is an uneven field. This, too, has to do with the issue of language. I’ve heard Albanians from Albania complain that the Albanian of Kosovars—even the standard Albanian—is somehow hard to read because of supposed syntactic influences from Serbian and other Slav languages of the former Yugoslavia. There have been cases, for example, when international authors who have already been translated into Albanian in Kosovo are then again translated in Albania and promoted as if the author were making their debut in Albanian! But despite the many difficulties coming at Kosovar writers from all directions, difficult times seem to inspire creativity.

August 2015

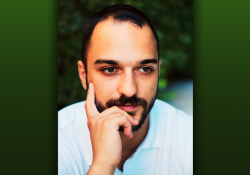

Ragip Luta is the director of FLO, Kosovo’s international Festival of Literature in Orllan. He has also directed FLOndon at the Poetry Cafe in London’s Covent Garden and has worked with Exiled Writers’ Ink to promote Kosovar poetry in Britain. He was an editor and producer for the BBC in London for two decades and has headed the BBC Albanian Service.

Ragip Luta is the director of FLO, Kosovo’s international Festival of Literature in Orllan. He has also directed FLOndon at the Poetry Cafe in London’s Covent Garden and has worked with Exiled Writers’ Ink to promote Kosovar poetry in Britain. He was an editor and producer for the BBC in London for two decades and has headed the BBC Albanian Service.

Peter Constantine’s most recent translation is Little Apples: New Stories, by Anton Chekhov. He has also translated works by Rousseau, Tolstoy, Machiavelli, and Thomas Mann.

Peter Constantine’s most recent translation is Little Apples: New Stories, by Anton Chekhov. He has also translated works by Rousseau, Tolstoy, Machiavelli, and Thomas Mann.