An Exile from the Sea with the Desert in His Mouth: A Conversation with Iossif Ventura

Born in Chania, Crete, in 1938, Iossif Ventura is a prominent Greek-Jewish poet and translator, a member of the Hellenic Authors’ Society, and the director of the electronic poetry magazine Poeticanet (www.poeticanet.com). His first volume of poetry, Υγρός κύκλος (Liquid circle), appeared in 1997 and his most recent volume, Το Παιχνίδι (The game), in 2015. Ventura is best known, however, for his two volumes of poetry about his experience and that of his fellow Cretan Jews during World War II. Ταναΐς (Tanaïs), which appeared in 2001, is named after the German ship carrying nine hundred prisoners—including the nearly three hundred Jews who comprised almost the entire Jewish population of the island—when it was sunk just offshore on June 9, 1944. Ventura revisited this theme again in Κυκλώνιο (Cyclone) of 2008, the title of which also references the Zyklon B gas the Nazis used on their victims in the extermination camps. The two volumes together were published in English translation in 2015 by Red Heifer Press under the title TANAIS: Kyklonio & Tanaïs. Two Poem Cycles Commemorating the Holocaust of the Jewish Community of Crete. Ventura currently resides in Athens.

Adam Goldwyn: Why did you decide in 2001 (when Tanaïs was first published) to tell the story of the Jews of Crete? And why did you revisit this theme in 2008?

Iossif Ventura: For many years growing up in Athens, I tried to put barriers around my war memories and my experience as a hidden child to escape the feelings of depression and sadness they generated in me. When I started publishing my poems and when my second book was favorably received by critics, a friend of mine suggested I write a poem for the Jews of Crete. In reality what he proposed was to dig deeply within myself and retrieve all the well-hidden trauma that was engraved on my unconscious.

I went to Chania and visited the house where I was born; I walked the streets of the old neighborhood near the Venetian port, which today is full of bars and restaurants, deprived of its Jewish population. I retrieved old photos, documents, and other things from my family. It was a very painful procedure, but I felt that I had a duty to the lost Jewish children. I felt that I had to talk for them, to tell their story, which is not well known even among other Jewish communities in Greece. Very few knew that the Germans forced all the Cretan Jews into the hold of a requisitioned commercial steamer named Tanaïs. Very few Greeks knew that this ship was torpedoed and sank along with its human cargo not far from the coast of the Greek island of Santorini. Very few knew that the loss of thοse people meant the end of old Jewish culture, which had endured for over two millennia and had given birth to great thinkers, philosophers, cabbalists, and poets.

It may seem metaphysical, but writing these poems, I sometimes felt that my pen was guided by those lost children, that I was sharing their terror, their cries, their last moments in the hold of the Tanaïs. Though the book was very well received, I still had the feeling that something was missing, that I had not finished my poem. There were missing verses, missing feelings that had to be expressed. This is why I wrote Kyklonio.

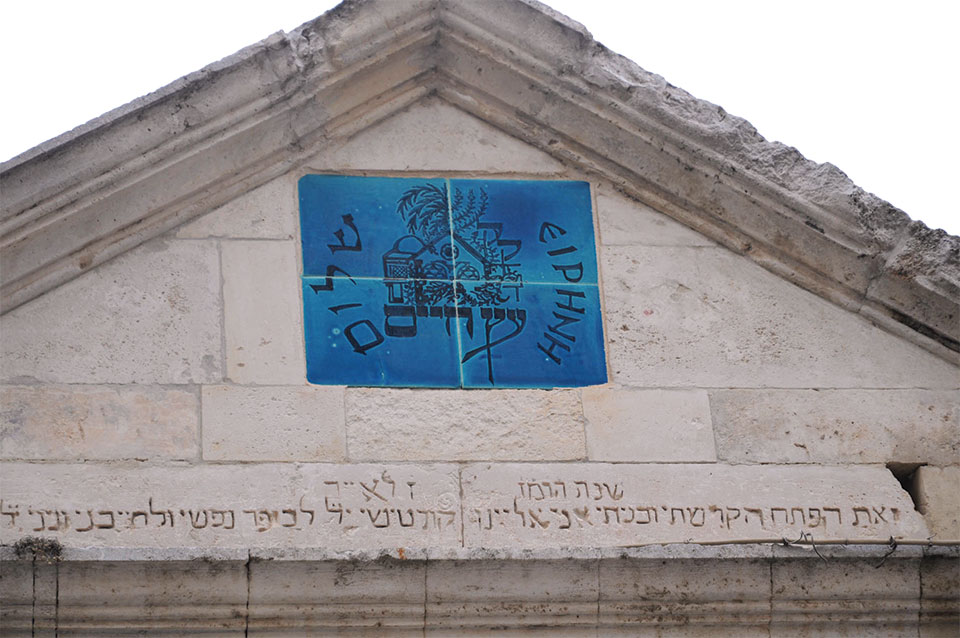

AG: In Tanaïs, you begin by listing the names and ages of the eighty-eight children who died when the ship sank, and then refer to the synagogue as an “orphaned tree.” Why did you choose this metaphor?

IV: Today I have the sad distinction of being the only living Jewish male born in Crete. All that remains of the Jewish community of Crete is a very old synagogue—a Venetian building—that bears the Hebrew name Etz Hayyim, which means “tree of life.” This “tree of life” is orphaned now, as all its children were lost.

AG: How did you avoid the fate of the other Jews of Crete, and what was your experience and memory of World War II?

IV: Both of my parents belonged to families that had lived in Crete for centuries. My ancestors probably immigrated to the islands of Zakynthos and Crete during the Venetian occupation. They were merchants and lived comfortably in houses outside the Jewish neighborhood.

In 1941 the Germans occupied Crete. My father had many Christian friends who loved him very much. In 1942 one of my father’s friends who was working as an interpreter for the Gestapo secretly informed him that the Nazis were preparing something very dangerous for the Jewish population of the island. He urged him to escape from Crete. My family followed this advice and although it was very dangerous, they decided to abandon everything in Crete and travel to Athens, embarking on a small caïque carrying carobs. There were six of us in this caïque: my father, my mother, my sister, my great-uncle, and a young Christian woman named Athina Varvataki who worked for my uncle. Athina was a very generous and courageous young lady, and she decided to follow our fate, refusing to return to her village.

After a ten-day journey full of dangers, we reached Athens. I will not go into the details of our adventures on this journey now, but in Athens the family separated. Athina pretended that I was her illegitimate child and hid with me for a year in the house of a Christian family in Ekali, a northern suburb of Athens. Imagine that next to the house where I was hidden, there was a German military camp!

AG: So you thought Athina was your real mother? Did you then also think you were a Christian? When were you reunited with your family? And did you stay in touch with Athina after the war?

IV: I was reunited with my family when Athens was liberated from the Germans. Athina stayed with us in the same house until I turned eighteen; she always took care of me. She was like a second mother to me. Actually, for many years I believed Athina was my real mother and that I was adopted into my family. Nevertheless, I never doubted my Jewishness.

AG: The epigraph from Tanaïs is from The Odyssey, while the epigraph from Kyklonio is from Jeremiah. You begin Kyklonio by giving your name in Hebrew, but written in Greek letters. Later in the poem, you quote two lines from a 2007 book entitled Studying the Holocaust in the Greek School:

Question: What is your name?

Answer: My Jewish name, or . . . ? My Greek name is . . .

These lines, these two poems, and your poetic work as a whole over the last two decades have all been strongly shaped by questions of identity. How do you answer the question posed in the lines above? How do you understand your Greek and Jewish identity or identities? Does poetry play a part in this self-understanding?

IV: It is said that our real homeland is our mother tongue. By looking at my identity in such a way I can easily identify myself as a Greek. I was born, educated, and lived almost all my life in Greece. I am deeply immersed in Greek culture and habits. I share the same fate and history as my Greek compatriots.

But even while growing up in Greece I had immense admiration for the Jewish pioneers populating the Holy Land; I followed their achievements in the Greek newspapers, and I felt very proud and happy when the State of Israel was born in 1948. I felt somehow that I was an immigrant in the country of my birth. I tried to read the Bible and to learn as much as possible about Jewish culture. I shared the same traditions, history, and dreams as the other members of the Greek Jewish communities, and although I am not religious, I have always had a deep respect for my Jewish heritage. I tried to read medieval Jewish poetry; I even dared to publish a book about it, including a small anthology of secular poems written mainly in al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). I also tried to study Jewish mysticism.

During the war, many Greek Jews changed their names because they were hiding their Jewish identity. But names are sacred, and they define our being.

These characteristics are well defined in my poems. Using epigraphs from The Odyssey and the Bible shows my debts to my Greek and Jewish heritage and their traces in me. Writing my name in Hebrew but with Greek letters, I project my double identity. During the war, many Greek Jews changed their names because they were hiding their Jewish identity. But names are sacred, and they define our being.

AG: Do you see yourself, then, as a poet in the Greek tradition, in the Jewish tradition, or in the tradition of world literature?

IV: It is natural that I am influenced by the Greek masters I have studied. But I have also studied English and French poetry, and I am very much interested in Occitan poetry and the troubadours of the twelfth century. I have published translations of troubadour poetry and essays about them in Greek poetry magazines. But I am also influenced by my Jewish heritage, and this differentiates my poetry from that of my colleagues in the Hellenic Authors’ Society. But writing the two elegies about my experience during the Holocaust, it makes me tremble knowing that in doing so I have followed some of the other great Jewish literary masters in speaking about this terrible period in our history.

AG: Why use poetry as the way to describe these events?

If the limits of our language are the limits of our world, as Wittgenstein has said, then with the help of poetry we can expand the limits of our language using the silences between worlds and between verses. This is how we try to talk about the “ineffable.”

IV: If the limits of our language are the limits of our world, as Wittgenstein has said, then with the help of poetry we can expand the limits of our language using the silences between worlds and between verses. This is how we try to talk about the “ineffable.” This is how we try to see life from above, from a distance, at an oblique angle. The poem talks like a teardrop. Why do we cry in moments of supreme happiness or supreme sorrow? It is because we cannot express our feelings with words. Poetry does this for us. It expresses overwhelming feeling, as the Romantics have said.

But today such a definition is insufficient. The artist must work hard to create new modes of expression, to adapt language to the circumstances of contemporary life, to contemporary patterns of speech and thought. Poetry helps us talk about the world as deeply as possible. When I am touched by inspiration, I feel something magical in that moment. But this inspiration, this newborn verse, is like a rough diamond. It must be taken to my laboratory and crafted to make it shine as much as possible. This is why and how I write my poems.

AG: After you give your name in Kyklonio, you describe yourself as an “exile from the sea with the desert in his mouth,” which to me is one of the most evocative and memorable lines in all of your work. What does this self-definition mean to you?

IV: My traumatic experiences as a hidden child during the Second World War shaped my character. I remember after the war I would cry while watching documentary films presenting the atrocities in the extermination camps or while listening to my family describe their terror when they were in hiding. I remember struggling to find some sort of psychological equilibrium.

All Greek Jews, like all Jews in the diaspora, are exiles. Exiles from the Holy Land, exiles from our communities, exiles from our history, exiles from our sacred language: it is obvious that words are insufficient for such a sorrow, for the feeling that something is missing, for our longing for our lost paradise. Because of this, our lips are always parched, and the winds of the desert make us feel a deathly cold.

July 2015