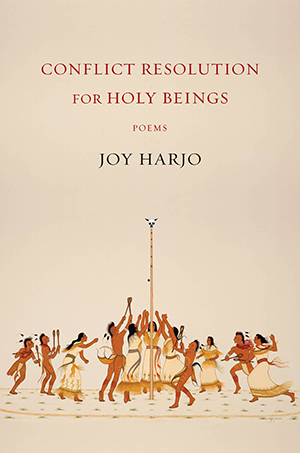

Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings by Joy Harjo

New York. W.W. Norton. 2015. 160 pages.

New York. W.W. Norton. 2015. 160 pages.

This is not merely a book of poetry. These are instructions for the soul, a song to lead the reader home. With Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings, the first lady of American Indian poetry arrives. In this volume, Joy Harjo reaches her full maturity as a poet and as a human being, a teacher for us all. This book is as precise as a ceremony and just as serious. Its subject matter is at the same time the story of Harjo’s people, the poet’s personal story, and the human metanarrative; it is life and the lessons we each must learn and pass on to future generations.

Harjo’s form, as we have come to expect, is grounded more in indigenous structures than in those of the Western canon. Divided into four sections for the four sacred directions of American Indian ontologies and the four phases of life, Harjo’s poetic offerings bring us the lessons she has learned that have brought her to spiritual maturity as an elder, a seer, a mystic, a singer, which brings us to healing and wholeness. These poems trace a life impacted by history, genocide, and Indian boarding school. They trace a journey through loss, abandonment, and heartbreak carried by song: Creek stomp dance, the ceremony that keeps the beat of the heart going, the drums of the ancestors; round dance song; a Creek lullaby; disco; powwow songs; Forty-Nine songs; Creek Sunrise song; and, of course, Harjo’s signature blues and jazz, the winds working with her to sing through her sax.

Throughout, there is a call and response with Harjo’s own poetic work, her own previous songs, notably “She Had Some Horses” and “Perhaps the World Ends Here.” The book also includes as a poem—and nicely so—the text of her children’s book For a Girl Becoming, written for her first granddaughter as she came of age as a young woman.

Harjo, now a grandmother to four granddaughters, comes fully into her role as matriarch in coming to terms with the loss of her friend, comedian Charlie Hill, and, more notably, the loss of her mother. Weary of travel, human greed, politics, and war in the world, Harjo becomes her own stable center and comes to her own healing through a literal return home to Tulsa. Early in the book, she says, echoing the Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys song, “Don’t take me back to Tulsa. I can only marry the music; the outlook is bleak.” Part of Harjo’s coming home, however, is finding her love at last, her new husband, Owen Sapulpa, to whom this book is dedicated.

As she imparts wisdom, Harjo calls us back into relation with the world around us and all of its creatures, with each other, with ourselves. “By listening we will understand who we are in this holy realm of words.” (Editorial note: The Academy of American Poets recently announced Harjo as the winner of the 2015 Wallace Stevens Award, in recognition of “outstanding and proven mastery in the art of poetry.”)

Kimberly Wieser

University of Oklahoma