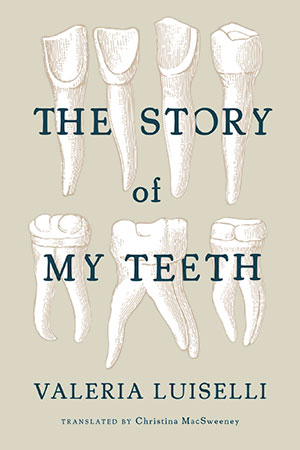

The Story of My Teeth by Valeria Luiselli

Minneapolis. Coffee House Press. 2015. 195 pages.

Minneapolis. Coffee House Press. 2015. 195 pages.

The Story of My Teeth is the third book of Mexican-born Valeria Luiselli, who lives in New York City. Except for the last chapter, the story is narrated by Gustavo “Highway” Sánchez Sánchez, “the best auctioneer in the world,” whose ars poetica is that the only honest way to enhance the value of an object is to tell a good story about it. His art is based on the hyperbolic method, namely, the exaggeration of facts about an item or, as he puts it, a better illumination of its qualities. Highway is no cheap trickster: he happily goes along with other masters of the hyperbolic method, to the point of buying teeth that allegedly belonged to Marilyn Monroe and having them transplanted into his mouth. In turn, he sells his own teeth one by one, claiming that they once belonged to famous writers and philosophers from Plato to Enrique Vila-Matas.

Not only does Highway justify forgery, he also happily engages in plagiarism—in other words, intertextuality. He often quotes his “uncles,” including Juan Sánchez Baudrillard, Marcelo Sánchez-Proust, and other famous figures. These quotations shift the atmosphere of the text depending on the reader’s degree of familiarity with these authors, but they are playful enough for us not to get confused even if we don’t get the erudite allusions.

Luiselli’s novel is not only for those initiated into postmodern theory. It is the result of meaningful engagement not only with literary giants but with the real world as well, an engagement that connects this otherwise lighthearted and elusive little book to the ground, injecting fresh blood into postmodern techniques. As Luiselli explains in her afterword, she was originally commissioned to write a work of fiction for the exhibition catalog of an art gallery that is funded by a juice factory. Instead, she decided to write a novel in installments, in collaboration with the workers of the factory, located in Ecatepec, outside Mexico City.

The exposure of collaborative efforts involved in making this book would not be complete without making the translator’s presence explicit. Luiselli’s translator, Christina MacSweeney, contributed a delightful timeline that is just as helpful as it is disorienting: besides giving signposts (political and literary events that took place during Highway’s lifetime), MacSweeney also added some random, insignificant events. Other insertions in the book include mottos by philosophers of language, aphorisms taken from Chinese fortune cookies, and a collection of photos of artwork as well as buildings and scenes in Ecatepec taken by factory workers.

A fundamental openness and curiosity make Luiselli’s work fresh and exciting. She is serious in her engagement with art, literature, and society without being arrogant or sententious—she is part of all those games, and is happy to acknowledge it. The topic she explores—fiction enhancing the value of an object—is quite pertinent in an age when the fate of so many people depends on hyperbolic personal statements, résumés, or news items.

Ágnes Orzóy

Budapest