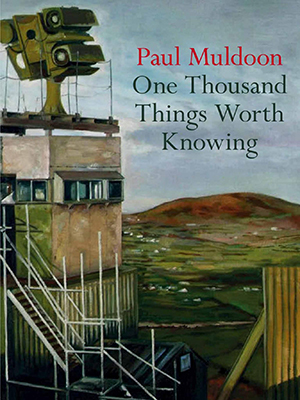

One Thousand Things Worth Knowing by Paul Muldoon

New York. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 2015. 117 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 2015. 117 pages.

The first challenging thing a reader encounters in this new collection by Paul Muldoon is the title itself. How literally can we expect the title to forecast the book? Is it really promising to be a selective compendium of facts urged on the reader, or an introduction literally to “things” (paintings, books, people, places) valued by the author, or possibly, and ironically, a challenge to large-scale knowledge acquisition at the expense of, say, wisdom or “the poetic”? These and other intricacies posed merely by the five words of the title do, in fact, forecast something of the reading experience of this volume, but the experience also includes a dazzling montage of arcane miscellany strung together at times only by the form of the poem itself.

Consider these two consecutive quatrains: “As the echoes of Sherlock’s high-pitched rebel yells / clung to the thatch in a smoke knot, / I’d only very gradually taken note / how Herbert Hoover’s casting spells // (and offering that “chicken in every pot”) / had come too late for Robert Frost, / cooped up as he’d been on the edge of a forest / with 300 Wyandottes.” We have the book’s characteristic disjunctive feel as the mind scrambles to connect Sherlock Holmes with Herbert Hoover with Robert Frost with Wyandottes and with the speaker’s ostensible meditation, all in a poem purportedly about—well, it’s hard to say. We are reminded of the wit and form of Byron; the encyclopedic mind of Pound; the zany, confusing abundance of Ashbery; and the technique of Jackson Pollack that relies heavily on the apprehending tendency of the human brain.

These poems constitute an impressive and entertaining performance that, of itself, offers certain satisfactions: wit, humor, invention, technical sophistication—all good things. For some readers, these will be enough; other readers, however, will find too much fancy footwork and showmanship. They will fatigue at the proliferating non sequiturs, the endless inkblots posing as far-ranging associative thought, the picaresque poems like handfuls of pearls left unstrung by an organicism of subject or feeling.

Poems can, of course, do many things, and these poems do some of them very well, but one can come away longing for what’s lacking, those things beyond the scope of public performance and the demonstrative, those special whisperings found especially in poetry. By all means, take in this book like a good show, but then be prepared to go home and seek out the human voices that speak beside you, there in the room with you. In his preface to the 1765 edition of Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson writes: “The irregular combinations of fanciful invention may delight awhile by that novelty of which the common satiety of life sends us all in quest, but the pleasures of sudden wonder are soon exhausted, and the mind can repose only on the stability of truth.” Each reader must decide what “truth” is and what things are most worth reading.

Fred Dings

University of South Carolina