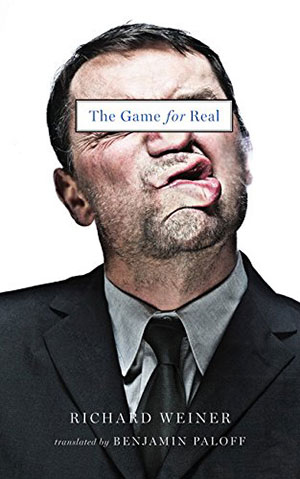

The Game for Real by Richard Weiner

San Francisco. Two Lines Press. 2015. 286 pages.

San Francisco. Two Lines Press. 2015. 286 pages.

Is there some inherent quality within the Czech lands that favors an inclination toward the absurd in their literature? Fans and adherents of Czech absurdism will no doubt welcome The Game for Real, a newly translated two-part novel by Richard Weiner (1884–1937). Weiner, who was both gay and Jewish during an “unforgiving” era, suffered a mental breakdown after compulsory military service in the First World War on the Serbian front.

He then left his native Prague and settled in Paris, the setting of The Game for Real. We meet up with our unnamed bachelor protagonist on the Paris metro headed toward his flat, where he keeps an inflatable doll for company. From the start, we grasp his existential loneliness and find that he keeps himself company largely through anxious, rambling interior monologues.

Eventually leaving his flat, he surrealistically begins to encounter his own double and then doubles of acquaintances in various Parisian cafés. Much of the text is subjective, dreamlike, and abstract: “More like you’d woken up in a strange land, but on a road that suggested an almost overbearing certainty that it led precisely to where you had to go, though you yourself have no idea where that is.”

There may not be a whole lot of action in The Game for Real, but the absurd is front and center. That absurdity is often a statement on the human condition, which no doubt is at play here. Doubles and doppelgängers may act as foils of our true selves that we suppress, or perhaps our bachelor fellow is undergoing a slow meltdown—a splintering in identity? Interlaced throughout his musings are anxieties and thoughts that rattle along in long paragraphic chunks, and just when we think we can’t take much more of these paranoid cogitations, Weiner hits us out of the blue with a plainly worded, spot-on insight: “We always drive like a runaway train into what we dread—through the barrier of premonition.”

Throughout the second part of the novel, themes of reality and truthfulness come to the fore as our fellow gets accused of a crime he may or may not have committed. The reader ultimately gets to decide. Reality and truth are up for grabs. The ruminations of an agitated mind continue all through The Game for Real (not for nothing was Richard Weiner dubbed “the Poet of Anxiety”). The latter third of the story devolves into Kafkaesque phantasmagoria as the story’s characters morph into other characters and then morph back.

It can take effort to read through the long blocks of angst and psychedelia in Weiner’s novel, but it’s well worth the effort. The sudden blunt insights blindside us and make us question our own values and realities anew. Perhaps it could also be a metaphor for life: slog through the drudgery of daily life and occasionally get rewarded with an insight.

Hats off to veteran translator Benjamin Paloff for a work that must certainly have been a challenge to translate.

Virginia Parobek

Lancaster, Ohio