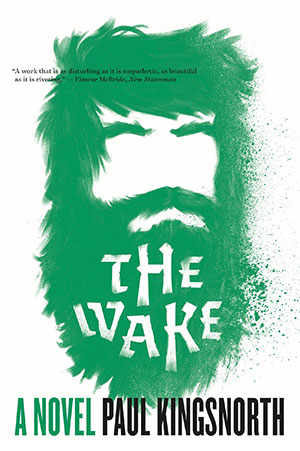

The Wake by Paul Kingsnorth

Minneapolis. Graywolf Press. 2015. 365 pages.

Minneapolis. Graywolf Press. 2015. 365 pages.

The Wake is the story of a man caught in the grips of two forces, historical and psychological. The force of history, the Norman Conquest (1066), destroys the home and family of Buccmaster, a prominent man in a small village. He begins his narrative as a truth-teller who provides a view of the conquest not dictated by the winning side. His perspective is colored by an antiquated ideology and by personal demons he is unwilling to acknowledge. Buccmaster is also a soothsayer, a self-appointed prophet of pagan revivalism. He thinks Christianity has sapped the strength and character of the English; he hopes, after centuries of Christian suppression, to revive the ancient Germanic mythology that honored Woden and the quasidivine Weland, archetypal smith who, Buccmaster supposes, crafted the sword bequeathed to him by his like-minded grandfather. He has just enough self-assurance, decidedly not charisma, to assume command over a small band of men dispossessed by the ruthless Normans; these men, hardly disciples, see no other path but to join Buccmaster in waging guerilla warfare against the French invaders.

In this setup, Paul Kingsnorth obviously hints at legends of Robin Hood, but he removes the romance by letting his narrator make inadvertent revelations about himself. One sees his self-importance, his brutality; one hears the (inner) voices that egg Buccmaster to self-assertion, admonitions spoken, he believes, by the submerged gods of his ancestors. Little by little we learn of his personal past, the conflict with his father; we are allowed a dim perception of how a long-simmering resentment erupts into violence that produces appalling collateral damage. If earlier we were reminded of Robin Hood, we are also reminded of Grendel, in the Old English epic Beowulf the monstrous emblem of strength ungoverned by wisdom. While John Gardner reimagines this monster as a modern antihero, Kingsnorth’s Buccmaster is in the end more like the medieval ghoul, a primitive, malignant sociopath.

A remarkable feature of this novel is that it is written in what Kingsnorth calls a “shadow language” vaguely reminiscent of Old English, a Germanic dialect akin to modern Dutch. This contrivance creates the feel of authenticity by using a spelling system that approximates the look of Old English (e.g., baec for back, treows for trees) and using a few Old English words that did not survive into modern English. Kingsnorth provides a glossary for such words (e.g., werod, “war band”) and for respelled words that are not easily recognizable (e.g., havoc, “hawk”). I wish he had glossed erce, which appears several times; its source and precise meaning elude me. Also a bit distressing is his treatment of grammatical forms. It is true that illiterate people often mangle the language they speak, but Old English was dependent on inflections in a way that modern English is not. An authentic Buccmaster would not have used thou for thee.

Daniel J. Ransom

University of Oklahoma